The Forgotten Steel Guitar

My 1950s Fender Stringmaster

Steel guitar – a stringed instrument played with a steel bar – is a fringy instrument these days. But there was a period in the first half of the 20th century when the steel or “Hawaiian” guitar was as popular as the “Spanish” guitar. I only recently realized how important steel guitar had been in popular and folk music styles in the US and it changed my idea about how quickly “traditional” music styles can change. Styles revered as ancient historical practices are more likely to be a fusion of diverse influences in the fairly recent past than an heirloom transmitted aurally and orally over centuries.

Gibson 1932 catalog

The rise of the steel guitar (and its fall from the 1960s on) was not inevitable and involved more than a small helping of serendipity. Surely, the discovery that pitches change when you slide a metal bar along a string must have been made countless of times in countless of places. One of those discovery moments was when 11-year old Joseph Kekuku walked along a railroad track with his guitar and found a steel bolt in 1885. Enthralled by the sound, he started to experiment with raising the strings, tunings, and manufacturing different steel pieces. His results must have fit well into existing Hawaiian music to spread quickly across the islands. The next serendipitous moment was that Hawaii became a US territory in 1900, creating much interest in all things Hawaiian, amplified during the 1915 Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. Hawaiian/steel guitars started appearing in company catalogs in the 1910s and then disappeared again after about 50 years.

The Hawaiian steel guitar rapidly spread to seemingly remote corners of the US. Jimmie Rodgers was among the first generation of recorded rural artists in the 1920s, after sound technology improved so that companies could make field recordings. Yet 1/3 of his recordings feature unambigously Hawaiian sounding guitar. Both Rodgers and the Carter family made their commercial debut when the Victor Talking Machine Company set up a temporary recording facility in Bristol Tennessee. Field recordings from that period became eventually seen as the epitome of traditional folk/country/blues music in the South. But now I think these were musical innovations rather than documentations of traditions. During his short career, Jimmie Rodgers recorded 31 songs featuring the steel guitar, starting with Blue Yodel No. 2 in 1928 (Ellsworth Cozzens on steel guitar). Many other songs included ukulele backup (he himself is credited as the ukulele player on one). On the 1929 recordings at the Jefferson Hotel in Dallas (which included Train Whistle Blues, Jimmie’s Texas Blues, Tuck Away My Lonesome Blues), the steel player was Joseph Kaipo, unambiguously establishing the Hawaiian connection. Jimmie Rodgers with Kaipo on steel:

Jimmie Rodgers recorded later in San Antonio with Charles Kailani Kama on steel guitar, including TB Blues and Travellin’ Blues. Kama had a successful group himself as Charles Kama and his Moana Hawaiians. After Jimmie Rodgers succumbed to tuberculosis (2 years after recording TB Blues), the Victor recording company signed his cousin Jesse Rodgers as a replacement. The band on Jesse Rodgers’ 1936 San Antonio recordings: Kama’s Moana Hawaiians. Even Maybelle Carter seems to have converted a guitar to a “Hawaiian setup” beginning in 1928 and several Carter Family recordings afterwards include steel guitar: Carter Family Little Darling Pal of Mine.

While the blues bottleneck slide technique may have appeared independently, the popularity of Hawaiian guitar undoubtedly influenced Black blues musicians. W. C. Handy, the “Father of the Blues,” described his memory of seeing a man in 1903 pressing “a knife on the strings of [a] guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars.”

John W. Troutman, the Curator of American Music at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, believes that the slide technique came from Hawaiians, although admits that his claim remains controversial. Supporting his argument are many pictures show early blues performers holding the guitar flat in their laps and fingerpicking like Hawaiian guitarists. Son House, a particularly influential (bottle neck) slide player, mentioned Hawaiian influences in interviews. At a minimum, the Hawaiian steel guitar’s history exposes a more intertwined and cultural blend in the musical history of the American South.

As audiences grew in the 1930s, instrument manufacturers looked for a way to amplify the volume. Unsurprisingly, given its popularity at that point, many of those developments were first for steel guitars, including the first attempts at mechanical amplification using aluminum cones.

Gibson 1937 Catalog

The very first mass produced electric guitar was George Beauchamp and Adolph Rickenbacker’s “Frying Pan,” which started shipping in 1932. Beauchamp did not get a patent for it until 1937, which allowed other manufacturers to enter. Gibson had several EH (electric Hawaiian) models in its catalog in 1937 (and later expanded its series of ES – electric Spanish guitars). But solidbody (Spanish) electric guitars did not arrive until the 1950s.

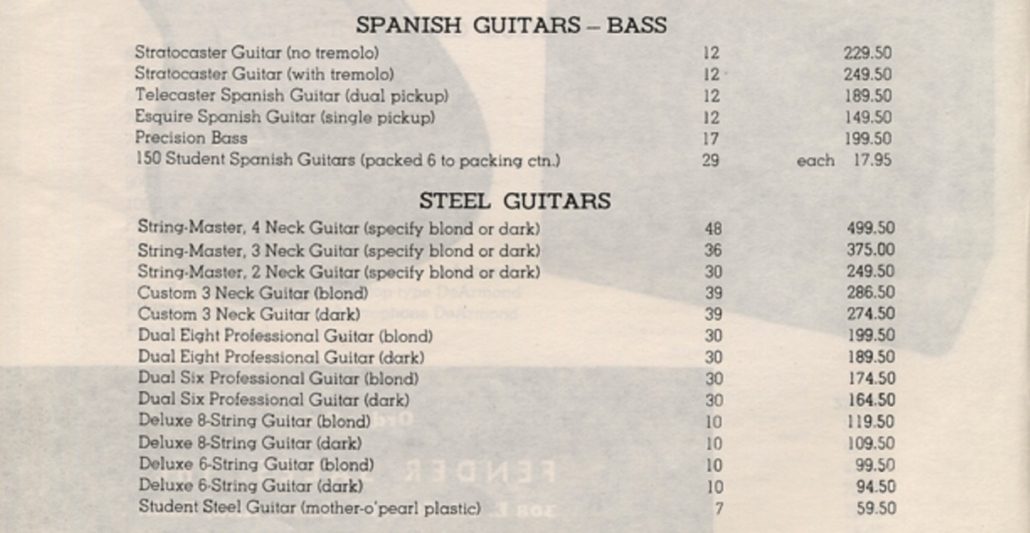

The steel guitar may have reached its zenith of popularity by the late 1930s and into the 1940s. Then an initially slow and later precipitous decline began. In 1953, Fender instrument catalogs still devoted 5 times as many pages to steel guitar than to other guitars. Even in 1955, after Fender had introduced the Stratocaster, there was a much bigger offering of steel guitars. The highest priced instruments were the steel guitars from the Stringmaster series then.

Fender 1955 Price List

Who would have guessed the reversal in collectability then? Currently, a clean 1950s Stratocaster is valued in the $50,000-100,000 range. I bought a mid-’50s Stringmaster a few months ago in excellent condition for $1000.

By 1960, Gibson offered a wide range of ES (Electric Spanish) guitars, but has dropped the EH (Electric Hawaiian) instruments. It still offered a few lap steels and also some of the new pedal steels (a bizarre instrument invented in the 1950s Pedal Steel The Most Steampunk of Instruments), but the tide had turned. Fender dragged some steel guitars into the 1970s, but they were unpopular fringe instruments. By 1980s, Fender had dropped its last steel guitars.