Pedal Steel – The most steampunk of instruments

The view of a pedal steel’s underside

The sound of a pedal steel guitar is iconic – no instrument conveys “country music” more immediately than a pedal steel. But even though I have heard it on countless recordings (and some live shows), I had not seen a pedal steel close-up until my son Obin bought one. Oh my, what a complicated piece of engineering! As if out a steampunk novel. Full of gears and cogs and metal, levers being pushed with your knees and feet. Only misses the steam engine.

But seeing his pedal steel got me interested in finding out more about the history – also because he left behind his old lap steel in C6 tuning for me to experiment with. A Magnatone, probably made in Los Angeles in the 1940s/50s.

The history of pedal and lap steel guitars turns out to be recent but convoluted. It started simple: pitches change when you slide a metal bar along a string. That discovery surely had been made countless of times in countless of places. But Hawaii became a particularly influential area for this approach to playing a stringed instrument.

The history of pedal and lap steel guitars turns out to be recent but convoluted. It started simple: pitches change when you slide a metal bar along a string. That discovery surely had been made countless of times in countless of places. But Hawaii became a particularly influential area for this approach to playing a stringed instrument.

Joseph Kekeku is the first documented slide guitar player and therefore often credited as the inventor of the Hawaiian steel guitar. In 1904, at the age of 30, he left Hawaii and toured mainland US and Europe extensively. Hawaii became a US territory in 1900 and that set off an interest in all things Hawaiian. Hawaiian music became hugely popular (also resulting in the ukulele boom.) The Hawaiian influence was so strong that guitars set up for playing with a metal bar (rather than pressing strings against frets) were called “Hawaiian guitars” to distinguish them from “Spanish” guitars.

It did not take long to reach for the “Hawaiian guitar” to reach geographically and musically remote areas of the US. The first country/folk recording of a steel guitar I could find was by Darby and Tarleton in 1927 – the same year as the first recordings by the Carter Family or Jimmie Rodgers! Jimmie Tarleton grew up on a farm in South Carolina, yet had found the “Hawaiian guitar” before radio and widespread recording. He recorded “Birmingham Jail” and “Columbus Stockade Blues” on November 10 1927. The slide playing sounds Hawaiian even when he sings about Georgia and wanting to be back in Tennessee. Nevertheless, Darby and Tarlton count as traditional Southern country/folk based on their material, personal background, and location.

Darby & Tarlton

Acoustic guitars are relatively quiet instruments and the Dobro and National companies in California started to build resonator guitars, using aluminum cones in an attempt at mechanical amplification. Dobro guitars – now a generic term like “Kleenex,” no longer referring to a single brand – are still a standard bluegrass instrument. Nationals became popular among blues musicians (at least after they were superseded by electrical instruments among professionals and therefore became cheap).

But the key change was electrification – not the mechanical amplification of the Dopyera brothers. That happened in the 1930s and suddenly the steel guitar was a central instrument in Western music. “Steel guitar rag” was a big hit for Bob Wills in 1936, written by and featuring a teenage Leon McAuliffe. (The linked video is more recent.) McAuliffe’s tune involved more than a little bit of borrowing: it is largely an electric version of a tune Sylvester Weaver had recorded as Guitar Rag in 1927 (when McAuliffe would have been 10 years old).

From the 1940s on, the electric steel guitar also featured prominently in the “country” end of Country & Western, quickly elbowing aside the hillbilly string-band sound popular in the 1930s. My progress learning the lap steel has me stuck in the 1940’s early electric era. Lap steels have most commonly 6 strings and are in a variety of tunings, with a C6 tuning (from low to high: C E G A c e) becoming popular in the 1940s. This tuning works immediately for almost all the steel parts on Hank Williams recordings. Two key players were Jerry Byrd and Don Helms who used variants of that tuning (but already with additional strings) with Hank Williams.

A 4-necked and 32-stringed Fender Stringmaster!

By the 1950s, lap steels experienced an inflation of strings and necks, driving a bigger wedge between amateurs and professional musicians who moved from a lap steel to multi-necked consoles. Fender’s Stringmasters series, offered from 1953 on, was available in configurations of up to 4 necks and 32 strings.

Yet even that was insufficiently flexible (complicated? interesting?) for some people and tinkerers started adding levers to change string pitches. Adding levers makes it is possible to make slurs/bends or change the quality of a chord while letting other strings ring (and keeping the bar). This creates the twangy sound that has come to identify country music. It’s difficult, maybe impossible, to execute cleanly without the machinery, although limited possibilities exist by bending behind the bar (pulling a string with a left hand) or angling the bar.

A watershed was the 1956 recording of Webb Pierce’s song Slowly. Bud Isaac, now on a pedal steel, pushed his pedals that bend up some notes from below into a ringing chord to harmonize with the other strings. This new sound became iconic in C&W music and an entire musical subculture took a sharp turn. Overnight, the expensive multi-neck consoles became outdated, except that there wasn’t a standard replacement.

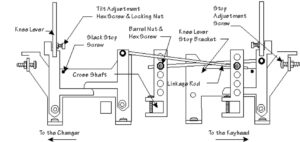

After “Slowly” was released, two steel players, Buddy Emmons and Jimmy Day, wanted pedal steels themselves and asked for some idiosyncratic setups that became somewhat standard. The pedal steel continues to be an instrument in transition, with a range of tunings, pedals, knee levers. Insiders have their “copedents” — statements or tables specifying somebody’s tuning, pedal and lever setup, string gauge combination. Just setting up the lever system is a mechanical engineering job. Here is a diagram for just two of many levers:

By the 1960s electric lap steels seemed obsolete. But how many people would really want to deal with a pedal steel? They were really expensive, hard to carry, clumsy. Still only attractive to a small group. At about the same time, electric (Spanish) guitars became widely available and the British Invasion made those far more desirable than that thing used for dad’s music. There is a glut of 1940s and 1950s lap steels available, many in fine shape, for the price of a cheap Asian acoustic guitar.

Many pedal steels have two necks, with different tunings, C6 on the neck closer to the player and E9 on the neck further away. Yet despite those names, the actual tuning is a lot more complicated (e.g. I was puzzled to learn that there is a D# string on the E9 neck). There are also 10 strings on each neck. Here is about as much as I figured out without getting totally confused. On the E9 neck, plucking the eighth string, sixth string, and fifth string sounds like an E-chord (and pulling on the top strings sounds nothing like an E or E9 chord). Pressing the two pedals furthest to the left seems to change it to a A chord. Then it gets tricky: Move the left knee to the right to push on that lever, while releasing pedal 1, but keeping pedal 2 pressed down and then it seems to be 3 notes of a B7 chord. Way too much mind and body gymnastics for me.

But Obin seems pretty happy to have fallen into the pedal steel rabbit hole with the Carter D-10 pedal steel that he found in Alabama. In his words: “I finally got a pedal steel guitar! I love this instrument! It’s teal-colored and a little complicated. And it makes those bendy sounds that get me every time.” What more can you want?