The Music We Danced To, Part 2

The Music We Danced To, Part 2

It turned out I picked a good time for an unemployed artist to look for work—Democrat Jimmy Carter had instituted a modern version of the WPA—the Works Progress Administration—which during the Great Depression put artists to work across this great land, writers, photographers, painters and musicians being called into service by FDR to use their art in service to their country. It was this program that employed photographer Dorothea Lange to take pictures of migrant workers in migrant camps in California—the place where she took her most famous photograph—Migrant Mother—which became one of the symbols of the Great Depression. Novelist John Dos Passos was hired to write travel guides for different regions of America—and they became indelible portraits of a nation caught—as the late Irish poet Seamus Heaney so eloquently put it—between hope and history. And eventually Woody Guthrie was hired for 28 days by the Department of the Interior to go up to Washington State and write songs for the Bonneville Power Dam Administration—which became his classic Columbia River songs and were finally rediscovered twenty-five years later and released on Rounder Records.

It turned out I picked a good time for an unemployed artist to look for work—Democrat Jimmy Carter had instituted a modern version of the WPA—the Works Progress Administration—which during the Great Depression put artists to work across this great land, writers, photographers, painters and musicians being called into service by FDR to use their art in service to their country. It was this program that employed photographer Dorothea Lange to take pictures of migrant workers in migrant camps in California—the place where she took her most famous photograph—Migrant Mother—which became one of the symbols of the Great Depression. Novelist John Dos Passos was hired to write travel guides for different regions of America—and they became indelible portraits of a nation caught—as the late Irish poet Seamus Heaney so eloquently put it—between hope and history. And eventually Woody Guthrie was hired for 28 days by the Department of the Interior to go up to Washington State and write songs for the Bonneville Power Dam Administration—which became his classic Columbia River songs and were finally rediscovered twenty-five years later and released on Rounder Records.

President Carter’s version of the WPA was called CETA—Comprehensive Employment and Training Act—which was designed to train people in transition for full-time jobs. And in what proved to the last hurrah of an enlightened period of American government—still connected in spirit to JFK and Jacqueline Kennedy’s unprecedented support for the arts—CETA included artists in its roster of trainees. I was able to get a paying job (albeit for minimum wage) working at the San Fernando Valley Arts Council, where I was hired to be an Oral Historian, to interview senior citizens about their projects working with our artists—poets, painters, dance companies, even puppeteers—who taught them their craft. Based on my extensive oral history report the Arts Council was refunded—twice—and able to continue serving the community of both seniors and children working in a multi-generational program we created for elders to hand down their skills and wisdom to children for their mutual benefit. During the second round of funding which my prose project report secured I finally worked up the nerve to tell my boss that I no longer wanted to be their Oral Historian—I wanted to be hired as an artist—specifically a folk singer. And in 1980 She agreed and I, for the first time, was able to file my IRS Tax Return with my job description as folk singer. It was one of the proudest days of my life.

During what proved to be the last year of CETA’s existence (it did not survive the first year of Ronald Reagan’s administration), I went into local senior centers, elementary schools, nursing homes, retirement homes, psychiatric rehab facilities, even prisons, and practiced and taught my craft. In the process of teaching it, I learned how to be a folk singer—how to hold an audience, how to tell a story, how to choose songs and sing in a way that connected with my audience. I also was able to practice daily and report that I was working on my job while doing it.

When I saw the writing on the wall and knew that my days working as a government-paid folk singer were numbered I started calling all of these places up that had secured my services for free and asking them if they would pay me to come back and keep doing what I had been doing as a CETA trainee. To my amazement, enough of them said yes that I was able to keep paying my rent on a small apartment on South La Brea. I had accumulated about thirty phone books by then, and called all over the city to widen my base of operations. Being self-employed also gave me the freedom to tell any boss who wasn’t treating me fairly to “take this job and shove it,” just like Johnny Paycheck said. I had literally hundreds of employers, not just one. That gave me just enough equality in the workplace to avoid the feeling of Joe Hill’s wage slavery. I was quite literally working for the people, not one corporation.

But at the same time, I had not solved my problem of writer’s block. I had to spend so much time mastering my craft—in all of its dimensions—performing, musicianship, hustling for bookings (I did around 400 shows a year at a myriad of institutions as well as some legitimate folk venues), and even graphic art in putting out my own publicity—that I had precious little time to write songs. I was in therapy and just trying to stay afloat from month to month. Walt Whitman’s injunction to “loaf and invite one’s soul” as a prerequisite for writing poems was way beyond my ken; I had precious little time to loaf. And Thoreau’s advice to would-be poets to “up-garret at once,” i.e., just stay in your cubbyhole until inspiration strikes was similarly foreign to me. There was always my next booking to get to.

But at the same time, I had not solved my problem of writer’s block. I had to spend so much time mastering my craft—in all of its dimensions—performing, musicianship, hustling for bookings (I did around 400 shows a year at a myriad of institutions as well as some legitimate folk venues), and even graphic art in putting out my own publicity—that I had precious little time to write songs. I was in therapy and just trying to stay afloat from month to month. Walt Whitman’s injunction to “loaf and invite one’s soul” as a prerequisite for writing poems was way beyond my ken; I had precious little time to loaf. And Thoreau’s advice to would-be poets to “up-garret at once,” i.e., just stay in your cubbyhole until inspiration strikes was similarly foreign to me. There was always my next booking to get to.

And yet, my psychotherapy with Dr. Carl Faber was working—even though I may not have been aware of just how. He (who had been my Psychology professor at UCLA during my undergraduate study in English) believed in me and gave me the confidence to believe I could eventually succeed as a folk singer and songwriter—even when I wasn’t actively writing songs. His extraordinary grace and passion in living a life of meaning planted a tree in my soul that inevitably began to bear fruit.

And then Ricky Nelson’s plane went down. I—who realistically was a “never was”—completely identified with this LA Times’ condemned “has been” and felt that, in coming to his defense, I was coming to my own. I had stumbled on what T.S. Eliot once called an “objective correlative,” a subject outside myself through which I could tell my own story. Byron had Don Juan; Shelley had the West Wind; Keats had his Nightingale and Grecian Urn. I had Ricky Nelson.

What a way to start out the New Year

To lose a friend like you

And it’s hard enough to say goodbye

But the lies that they’re calling true

I opened the morning paper

The first thing New Year’s Day

The first thing New Year’s Day

They said your plane went down

And they went on to say…

They called you a teenage idol

And a has-been at twenty-five

Well you were more than that to those who know

It’s hard to just survive

And those who make their living

Wielding a poison pen

They must have hearts of stone

Not to remember when:

“We marched to If I Had a Hammer,” I sang;

“And we dreamed to Blowing in the Wind;

“We screamed for Sergeant Pepper

“And his Lonely Hearts’ Club Band;

“But yours was the music we danced to

“When we turned the lights down low

“And Poor Little Fool…played on the radio.”

© 1986 Grey Goose Music (BMI)

I had everything I needed; I was an artist; and just like Bob Dylan said, I didn’t look back.

In Memoriam: Carl A. Faber, Ph.D. (1935-1996), teacher, friend, and psychotherapist.

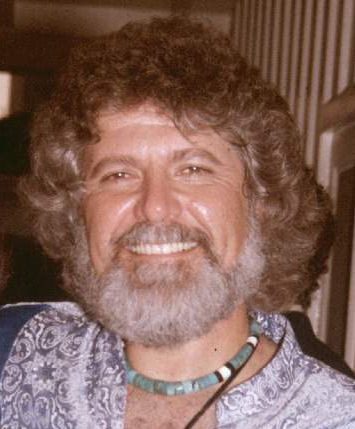

On Saturday, March 8 Gerry Fialka interviews Ross Altman on stage at the UnUrban Coffee House—4:00 to 6:00pm; talking and singing about his work, folk music and the creative process; 3301 Pico Blvd., Santa Monica, CA 90405 310-315-0056; free and open to the public, THE UNURBAN is proud to host MESS (Media Ecology Soul Salon); The public is invited to these engaging interviews by Gerry Fialka with modern thinkers who’ll address the metaphysics of their callings and the nitty-gritty of their crafts.

Ross Altman will perform in five upcoming tributes to Pete Seeger:

1) Saturday, March 1, a “Pete Seeger Sing-Along Tribute” at the Church in Ocean Park, from 4:00-7:00pm; 235 Hill St., Ocean Park, CA 90405; $10 310-399-1631

2) Saturday, March 8, a “Celebration of Pete Seeger–His Songs and Spirit” at Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum, from 1:00 to 4:00pm; $10; 1419 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd., Topanga, CA 90290;(310) 455-2322

3) Sunday, March 9, a “Tribute to Pete Seeger” at The Coffee Gallery Backstage in Altadena, 8:00pm; 2029 N. Lake Blvd in Altadena, CA 91001 626-798-6236

5) Saturday, April 5, a “Memorial Concert for Pete Seeger” at the First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles, from 2:00 to 5:00pm; 2936 W. 8th St., LA, CA 90005; $20; 213-389-1356, a church benefit produced by Ed Pearl for the Ash Grove Music Foundation

4) Sunday, May 18 “Sing Out for Pete!” at the Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest & Folk Festival at 4:30pm on the Railroad Stage (solo performance); Paramount Ranch 2903 Cornell Road, Agoura Hills, California 91301; 805-370-2301

Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature; he may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com