THE MAGNA CARTA TURNS 800

The Magna Carta Turns 800

Epigraph: When tyrants tremble sick with fear/To hear their death knell ringing/When friends rejoice both far and near/How can I keep from singing?

Epigraph: When tyrants tremble sick with fear/To hear their death knell ringing/When friends rejoice both far and near/How can I keep from singing?

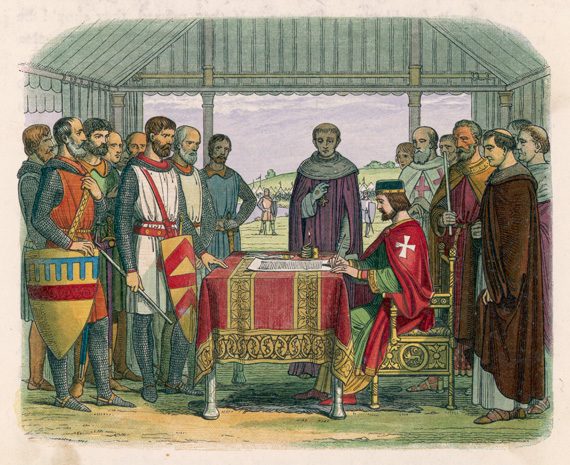

DATELINE: Runnymede, England, June 15, 1215. 800 years ago, King John’s Barons forced him to sign the founding document of English liberty—“The Great Charter,” “The Magna Carta.” Written in Latin, it was the first organized effort to drive a wedge between Noblemen and the King, guaranteeing to British Nobility rights which had formerly been allocated only to the King. That was the beginning of such rights eventually making their way down to the bottom rung of the social order and permeating a democratic society.

That document now resides in the Bodleian Library of the British Museum; I have a framed replica which I found a number of years ago at an Out-of-the-Closet thrift shop. Outside of my Gibson J-200 guitar it is my most treasured possession—a daily reminder of the human rights that became the animating principle of the American Revolution, the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and Bill of Rights.

Thomas Paine wrote the book The Rights of Man in support of the French Revolution—which ironically got him expelled from England—before the phrase “human rights” had even been coined—by American Transcendentalist philosopher, naturalist and poet H.D. Thoreau—in his groundbreaking essay Civil Disobedience—the cornerstone document of the defense of individual rights over the state, and the concept that led to Eleanor Roosevelt’s passage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, Mahatma Ghandi’s passive resistance on behalf of Indian Independence and Martin Luther King’s nonviolent struggle for civil rights. These modern shrines to human progress emanate from the opaque but eloquent Magna Carta that celebrates its 800th anniversary this year.

If folk music stands for anything worth celebrating it is setting these stories to music and articulating their ideals in song. Every freedom song, every civil rights anthem, every patriotic hymn to America and its values, every cowboy song that stands for the cowhand against the trail boss, every union song that hails the working class hero against the owners who exploit their labor, every sea shanty that sides with the betrayed cabin boy against the ship’s captain, every lumberjack ballad that celebrates a modern Paul Bunyan as “Ye mighty sons of freedom that…range the wild woods over” is a stand in for those 11th Century resistors to the princes and kings who ruled their destiny with an iron hand.

Folk music—as the late Pete Seeger devoted his life to demonstrating—is the great rallying cry for democracy, or as Aaron Copeland so grandly put it, the Fanfare for the Common Man. As to be expected, no one put it more eloquently or bluntly than Woody Guthrie’s own Magna Carta of what he stood for as an artist:

I hate a song that makes you think you’re not any good

I hate a song that makes you think you’re just born to lose

Bound to lose

Cause you’re either too old or too young

Too fat or too slim

Too ugly or too this or too that

Songs that poke fun at you on account of your bad luck or hard traveling

I’m out to fight those kinds of songs to my very last breath of air

Or last drop of blood

I’m out to sing the songs that will prove to you that this is your world

And if it has hit you pretty hard or knocked you down for a dozen loops

No matter what color or size you are

Or how you’re built

I’m out to sing the sings that’ll make you take pride in yourself and in your work

Oh I could hire out to the other side—the big money side

And get several dollars every week just to quit singing my own kind of songs

And sing the kind that run you down still further and poke fun at you even more

But I decided a long time ago that I’d starve to death

Before I’d sing any such no good songs as that

Your radio waves and jukeboxes and movies and songbooks

Are already filled and running over with such no good songs as that anyhow

For the most part the songs that I sing

Are made up by all sorts of folks

Just about like you.

From 1215 to 1679 marks the first major turning point in translating those principles into common law—that would apply to every Englishman regardless of class—and that is the Law of Habeas Corpus, or roughly translated “To Have the Body.” It laid out the first concept of Due Process—which would eventually make its way into the 4th Amendment of our own Bill of Rights. It required that a prisoner could not be held without being informed of the charges against him; and that broadly speaking someone could not be charged with the capital crime of murder if their were no body in evidence. Subsumed within that requirement was the necessity for the state to present the murder weapon—a constant theme of virtually every modern cop show from Law and Order to NCIS.

As one surveys these features of the vanguard of Civil Liberties—the British Law of Habeas Corpus—it gradually becomes clear why Guantanamo has become such a bone of contention in the American debate; for it is virtually defined by what it does not have—and that is due process in all the respects noted above. Prisoners are routinely detained without any charges being filed against them; no proof of a specific crime is required; simply being suspected of being “terrorists” is sufficient cause to imprison them for life. Lincoln would have gagged at the thought that he was accused of “suspending Habeas Corpus” during the Civil War when compared to the routine violation of every legal norm at the US prison in Guantanamo. And yet seven years after President Obama promised to close the most notorious prison in US history it remains open for business with no plan for its closure. Every time I sing Guantanamera I therefore remind my audience that the song is of lasting value in being a constant reminder of what Guantanamo used to represent—one of Cuba’s most beautiful places as described by their national poet Jose Marti—and set to music by Pete Seeger and Hector Angulo—versus what it now represents—a place where “los pobres de la tierra” (the poor people of this earth) languish in what amounts to permanent confinement in a lawless prison.

And yet, in the borough of Brooklyn prosecutors have just convicted a US veteran of trying to join ISIS—while observing the laws of jurisprudence—demonstrating that the “war against terror” can be successfully fought without abandoning due process of law.

The Magna Carta—in all its “raging glory” (Bob Dylan, from Idiot Wind, 40 years old this year) thus shines a grim light on what has become of the United States commitment to Due Process of Law. But you don’t have to read the Magna Carta. Just listen to Guantanamera: Con los pobres de la tierra (With the poor people of this earth)

Quiero yo mi suerte echar (I share my fate)

Con los pobres de la tierra

Quiero yo mi suerte echar

El arroyo de la sierra (The small streams of the mountain)

Me complace más que el mar (Please me more than the wide ocean).

That is the power of song: it casts a steady ironic glow around one of the darkest chapters in recent history. Jose Marti’s imperishable lines make it impossible not to think of this place in the context of Cuba’s rich history—in the same way that Leadbelly’s The Midnight Special transforms a prison song into a freedom song; and his Let It Shine On Me (both detailed in my recent review of Smithsonian Folkways boxed Lead Belly collection) transforms a slave spiritual into an Underground Railroad song.

The greatest folk songs transcend their moment and become constant bellwethers of freedom and the courage of those who sacrificed to achieve it. Without them we would have only the words of such documents as the Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights; but not the music. And it is the music which—in Pete Seeger’s wonderful phrase—assures us that “Throughout this world of danger and sorrow/We still may have singing tomorrows.”

This June 14 (June 15 in England) we will therefore celebrate the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta; for when I think of it, how can I keep from singing?

Sunday May 17 Ross Altman performs at the Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest and Folk Festiva, 4:00 PM at the Railroad Stage; a celebration of Joe Hill and the IWW in commemoration of the Centennial of his execution November 19, 1915 in Salt Lake City, Utah, which just reinstated the firing squad that killed him. www.topangabanjofiddle.org

Saturday May 30 Ross Altman performs in the Claremont Folk Festival. folkmusiccenter.com/folk-festival/

Sunday June 14 (June 15 in England) Ross Altman hosts and performs with friends in a celebration of The Magna Carta@ 800: The Birth of English Liberty at Beyond Baroque, 681Venice Blvd, Venice 90291 7 PM, $10; www.BeyondBaroque.org(310) 822-3006.

Los Angeles folk singer Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com