The Evolution of the Harp

Folk Harps with “Sharping” Levers

When a harp is mentioned, most of us probably picture the large orchestral harps. But those harps are the current stage of an instrument that has evolved from a much simpler beginning. It most likely began when early man noticed that his hunting bow made a note when plucked. From this came the lyre and later the harp. The smaller folk and Irish harps (Figure 1) are still in common use for non-orchestral music and have come to terms with the chromatic problem by implementing a system of “sharping” levers. Each string has a lever that can be turned to contact the string and raise it one half step. For example, imagine that the strings are tuned to the key of C, no sharps or flats. To change to the key of G—the key of one sharp—you would turn the sharping levers on all of the F-note strings to change them to F sharp (F#). Now if you start playing your scale on a G instead of a C you will be in the key of G.

Re-inventing the Flat

This approach will work fine for all of the sharp keys but the flat keys are not so easy and may not even be possible. To illustrate this, let’s use the sharping levers to set up the harp for the key of F, the key of one flat. All of the B strings have to be changed to Bb (B flat) accomplished by using the sharping levers. At first this seems cleverly do-able since the A strings can be tuned to A# which sounds the same as a Bb. That’s fine but now the A’s are lost from the scale and that is not okay. One work-around in use is the so-called Eb tuning where the instrument is still tuned to a C scale but with the B, E and A sharping levers already engaged and available for use as flatting levers when they are disengaged. This allows the instrument to be played in the three flat keys of F, Bb and Eb however; only the first four sharp keys of G, D, A and E are still available.

The Double Action Harp with Pedals

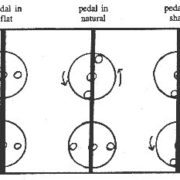

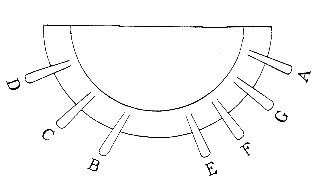

A practical solution finally became available in 1810 when Sebastian Erard of Paris was granted a patent for his “double action” harp. A harpist could lower as well as raise the pitch of any string at will and the harp could be played in any key. The harp could now be included in the orchestra giving it an enhanced air of legitimacy. This “double action” harp replaced the hand-operated sharping-levers with seven three-position foot-pedals (Figure 3), one for each of the seven white keys on the piano. Moving the F pedal from the middle notch to the lower notch (Figure 4) changes all of the F strings to F-sharps in one motion.

A Not So Simple Instrument

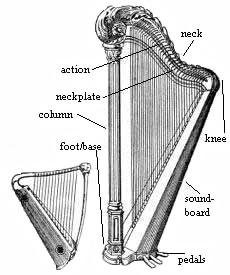

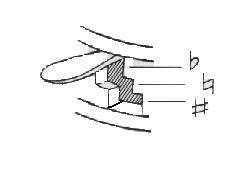

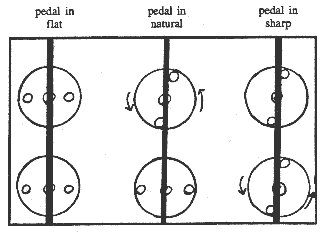

While this system transcended the chromatic limits of the previous harps, the resulting harp was no longer a simple instrument. Pedal movements needed to be transferred across the base of the harp and then up one of the seven rods inside the hollow front column (Figure 2). At the top of the column the rod movement is transferred through a series of brass linkages to all the strings of the same name. Near the tuning pegs at the top of the instrument, each string has two disks with protruding pins that can engage the string. The pedal can engage one (natural), both (#) or neither (b) of the disks to affect the pitch by changing the length of the string (Figure 5). The once simple harp is now a complex piece of equipment with many moving parts.

Interesting Things to Know About the Concert Grand (Pedal) Harp

If laid out end to end on the ground the 1000-plus moving parts of the modern Concert Grand Harp would be over seventy feet long. The 47 strings can exert up to two tons of tension on the 80-pound six-foot frame. Harps are still hand made, some taking two years to construct and selling in the range of $9,000 to $50,000. The six and a half octave range of the harp almost covers the full range of the piano. The bottom string C is three notes above the piano’s lowest note of A and the top string G is only four notes below the piano’s highest string C. Since the harp doesn’t have the piano’s black keys for the musician to use as landmarks the convention is to use red strings for all of the C’s, black or dark blue strings for the F’s and white strings for all the rest. The harpist, like the pianist, uses the right hand primarily for melody and the left hand for accompaniment but, unlike the pianist, uses only the thumb and the first three fingers of each hand. The little or “pinkie” finger is not used at all.

That’s it for this issue. I hope I have been able to show you how others throughout history have attempted to help you stay tuned.

Roger Goodman is a musician, mathematician, punster, reader of esoteric books and sometime writer, none of which pays the mortgage. For that, he is a computer network guy for a law firm. He has been part of the Los Angeles old-time & contra-dance music community for over thirty years. While not a dancer, he does play fiddle, guitar, harmonica, mandolin, banjo & spoons. Roger has a penchant for trivia and obscura and sometimes tries to explain how the clock works when asked only for the time. He lives with his wife, Monika White, in Santa Monica.