NORTHUMBRIAN SMALLPIPES: AN INTERVIEW WITH DICK HENSOLD

Northumbrian smallpipes: An Interview with Dick Hensold

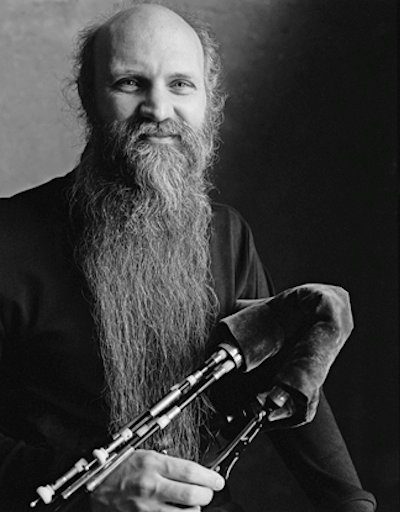

Bagpipes are very traditional instruments, although history hasn’t been kind to many of them. Popular in the medieval ages, bagpipes fell out of favor as Western classical music developed, and they experienced a long decline. Some of these pipes have seen resurgence or were revived as interest in traditional music increased and there is a much more diverse world of bagpipes out there than just the Scottish Highland pipes. Dick Hensold is an expert on bagpipes and his main love are Northumbrian smallpipes.

Bagpipes are very traditional instruments, although history hasn’t been kind to many of them. Popular in the medieval ages, bagpipes fell out of favor as Western classical music developed, and they experienced a long decline. Some of these pipes have seen resurgence or were revived as interest in traditional music increased and there is a much more diverse world of bagpipes out there than just the Scottish Highland pipes. Dick Hensold is an expert on bagpipes and his main love are Northumbrian smallpipes.

Roland Sturm (RS): Where do the Northumbrian smallpipes fit into the wide history and traditions of bagpiping?

Dick Hensold (DH): Many kinds of bagpipes are found from all over Europe, and they vary greatly in tone, volume, tuning, and especially in elaborateness of construction. I usually define “traditional” as meaning, “passed down continuously for many generations”. Many of the older kinds of pipes have died out as “traditional instruments”. There has been some revival of these old pipes, which now exist only in history, but the techniques and playing style of these revival instruments has to be re-invented to some degree, and much is inevitably lost. But there are a few pipes that have stayed continuously active as a living tradition, maintaining what is considered a very old traditional playing style. There are three such traditional pipes from Great Britain and Ireland: the most familiar are the Scottish great Highland bagpipes, followed by the Irish uillean pipes. By far the rarest are the Northumbrian smallpipes. Northumberland is in the northeast of England, just across the Tweed River from Scotland. A strong connection with the Scottish Lowlands gives traditional Northumbrian music a “Celtic” feel.

RS: The Scottish Highland pipes tradition in the last 150 or so years seem to be more a military than a folk tradition. Even solo piping at Highland Games is very regimented and mostly you see the pipes as part of marching bands. But that hasn’t spilled over to Northumberland?

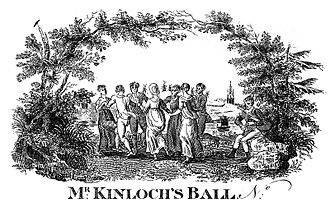

DH: Not at all, but mostly because Northumbrian smallpipes are too quiet to be very effective outdoors as a marching instrument. Their role over the centuries has been as an indoor parlor/ pub/ folk/ traditional music instrument, and only occasionally used for dancing. [Bewick engraving from around 1800]:

Northumbrian smallpipes have remained a traditional instrument in Northumberland for at least 300 years, but the tradition has hung by a thread on several occasions, and maybe it was most endangered in the middle of the 20th century. The tradition in Northumberland was re-kindled in the 1960s and ‘70s by younger musicians in collaboration with the remaining older players, and so the thread remained unbroken. Northumbrian smallpipes have grown in popularity since then (particularly in Northumberland), but it is still a rare instrument. I have only located one or two Northumbrian smallpipers in Southern California and there may just be a dozen in all of California.

RS: Yes, that sure is different from Highland pipes, there seem to be hundreds of players at every Highland game in California! Highland pipes are mouthblown, only 9 different notes, and a range of just over an octave, but you use bellows and have a much larger range. What is the difference between Irish and Northumbrian bagpipes?

DH: Northumbrian smallpipes are sometimes mistaken visually for (Irish) uillean pipes, because both use a bellows to fill the bag. Use of the bellows allows the reeds to be scraped more delicately, which allows more control and refinement in tone, volume, and response. Both instruments are also very elaborately designed and constructed, and so are comparably highly developed technically, having a wider range and more chromatic capabilities than the Scottish pipes.

RS: What do you mean by “highly developed technically”?

DH: Many bagpipes, such as the Scottish Highland pipes, have a range limited to barely a diatonic octave—eight or nine notes in all. This is also true of all the Mediterranean and Eastern European bagpipes, and of the Swedish pipes, which I also play. For example, the Swedish säckpipa is a very simple instrument that you can make out of materials at hand with a pocket knife, needle, and an iron rod. The säckpipa’s sound is wild, matching its primitive construction, but it’s also very difficult to get in tune! So its use, like its range, is somewhat limited. In this video, I play Swedish bagpipes:

The Northumbrian smallpipes are the evolutionary opposite, a highly developed, versatile instrument that requires incredible craftsmanship in its construction. Northumbrian smallpipes have a system of keywork that extends the range of the instrument to two octaves and can make it almost completely chromatic within that range. This allows it to play not only traditional Northumbrian smallpipe music, but to play in several different keys, render songs effectively, and even play fiddle tunes, which now comprise much of the Northumbrian smallpipe repertoire.

RS: OK, so then what IS the difference between Irish and Northumbrian bagpipes?

DH: The big difference between an uillean pipe chanter (the melody pipe) and a Northumbrian smallpipe chanter is the construction and the acoustics. This drives the difference in every other aspect of the instruments. An uillean pipe chanter has a conical bore inside (so the bottom of the pipe is bigger than the top), and the Northumbrian smallpipe chanter has a cylindrical bore. This gives them very different sounds and volumes. A comparable comparison is an oboe (conical) with a clarinet (cylindrical). The Northumbrian smallpipe chanter also has a double reed like an oboe, so its sound is sort of a cross between on oboe and a clarinet. In addition to its rich, mellow tone, the Northumbrian smallpipes also have a volume that balances well with other acoustic instruments, such as guitar, flute, fiddle, etc. The balance, blend, range, and musical versatility make the Northumbrian smallpipes a great instrument for playing in bands.

RS: When were the keys added? Is this a refinement paralleling other western instruments (e.g. brass instruments getting valves). Does it change the “tradition”?

DH: Adding keys to extend the range is not exactly a new development—it took place about 200 years ago—but the classic old Northumbrian smallpipe repertoire is mostly made for the simpler 8-note version of the instrument. But the basic traditional playing style seems not to have fundamentally changed.

RS: Tell me about this older piping tradition—do people still play these old tunes, or do people mainly play repertoire like fiddlers?

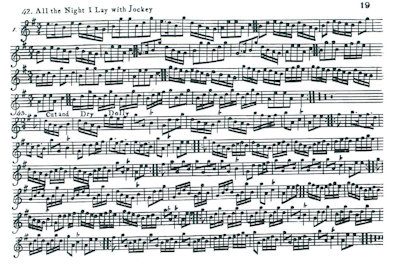

DH: A really cool thing about the Northumbrian smallpipes is that the piping tradition preserves a very old style of tune that was known in the Scottish lowlands and in Ireland hundreds of years ago (we know this because this type of tune appears in old manuscripts in those places). This style has died out in the tradition elsewhere, but remained alive continuously in Northumberland. In fact, there is one tune for which there is very good documentation proving it stayed in fashion among traditional players (both literate and non-literate) for at least 250 years. Here is an example of an older tune—the Northumbrian smallpipes are panned to the right channel, and the accompanying Scottish smallpipes are on the left:

All the Night I Lay with Jockey Richard Hensold

RS: Other than tone, what else sets the Northumbrian bagpipes apart?

DH: One of the particular characteristics of Northumbrian smallpipe music is the “staccato” style. The chanter is closed at the end, and this allows the chanter to be silent for a brief moment between notes. This gives the piper control over articulation and a broad range of expression—the player can play smoothly, or articulately, or even bubbly at will.

RS: I’m puzzled. Bagpipes and staccato don’t go together in my mind. They have a continuous sound, both from drones and chanter. This continuous sound is part of the charm and the limitation – the squealing pig sounds at the end or when things get out of control. Highland pipes have this complicated system of ornaments to create rhythmic phrasing, a way around not having a staccato option.

DH: True, that’s a big part of the effect of Highland pipes. And staccato is very unusual for most bagpipes, which have an uninterrupted sound. Northumbrian smallpipes can introduce ornaments common to other piping styles, or very few, as the occasion requires. They can also slur or slide at the will of the performer. But playing with more staccato is greatly desired for the older repertoire. It is even mentioned in the 1777 Encyclopedia Britannica entry under “Bagpipe. Small”! (See the previous audio clip for an example of staccato playing—note the occasional “bubblyness” in the Northumbrian smallpipe part.)

RS: Often bagpipes are solo instruments, but you seem to play regularly with others.

DH: That’s what you can do with Northumbrian smallpipes! Right now, I am touring with Patsy O’Brien who is a singer and guitar player. Half the concert is traditional songs sung by Patsy from Ireland, Scotland, England and Northumberland, and half is instrumental music from the locales above, plus Cape Breton Island. In addition to the Northumbrian smallpipes, I will also be playing Scottish Highland reel pipes (a quieter version of the Highland pipes, known for dance music in the 18th and 19th centuries, and revived in the past generation), and various whistles. And I can back up Patsy with Northumbrian smallpipes accompaniment when he flatpicks Irish tunes on guitar —just try doing that with a Highland bagpipe! (here’s an example:)

Dick and Patsy are appearing at Alvas Showroom on November 8th, and at Caltech on November 9th.

Friday, November 8, 2019 – 8:00 pm

Alvas Showroom Concert info 1413 W 8th St, San Pedro, CA 90732 310-833-3281 Tickets: $20

————————————————Pasadena Folk Music Society Concert info Saturday, November 9, 2019 – 8:00 pm Caltech Beckman Institute Auditorium, 400 South Wilson Ave., Pasadena, CA 626-395-4652 Tickets: $20 for adults and $5 for children and Caltech students. Tickets available at the Caltech Ticket Office by calling the box office.

Roland Sturm is Professor of Policy Analysis at the RAND Graduate School and usually writes on health policy, not music. He is the talent coordinator of the Topanga Banjo Fiddle Contest. These days he mainly plays upright bass and mandolin.