John Lomax Cowboy Songs Centennial

The John Lomax Cowboy Songs Centennial

1910-2010

This essay is dedicated with love to Marjorie Meghrig, founder of Bloomsbury Book and Art Gallery in Los Angeles, who in 1980 gave me a rare book by John Lomax, thinking I might need it one day. She also produced my first concert here-at Bloomsbury. Without realizing it, she started me on a two-fold path as performer and writer.

This essay is dedicated with love to Marjorie Meghrig, founder of Bloomsbury Book and Art Gallery in Los Angeles, who in 1980 gave me a rare book by John Lomax, thinking I might need it one day. She also produced my first concert here-at Bloomsbury. Without realizing it, she started me on a two-fold path as performer and writer.

When did the 20th Century folk revival begin? Baby Boomers argue that it began in 1963, at the Newport Folk Festival, when a young Bob Dylan (who turned 69 on May 24) performed Blowing in the Wind with Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger and the Mississippi Freedom Singers on closing night, a moment captured by Vanguard Records and released in their Newport Folk Festival series.

Wait a minute, claim their frat and sorority house brothers and sisters, the folk revival really began five years earlier, in 1958, with the Kingston Trio’s recording of a song (originally collected by Frank Warner from fretless banjo maker Frank Proffit), the Ballad of Tom Dooley. It went to number 1 on the Hit Parade and paved the way for the likes of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Peter Paul and Mary to bring folk music into the mainstream of American popular culture. No Kingston Trio, they argue, and no Peter, Paul and Mary.

Hold on, not so fast, say the purists, the Folk Revival per se began three years earlier, on Christmas Eve, 1955, to be precise, when the blacklisted Weavers came out of their forced retirement to reunite at Carnegie Hall, a concert which was also recorded by Vanguard Records and released as The Weavers Live at Carnegie Hall. “No Weavers,” the purists argue, “no Kingston Trio.”

Aren’t you forgetting something, claim their parents-what about the Weavers before they were blacklisted-in 1950, when their recording of Leadbelly’s theme song Goodnight Irene shot to the top of the Hit Parade and stayed there for 13 weeks, leading Life Magazine to vote it “the song of the ½ Century”? “Thus,” they conclude, “the folk revival really began in 1950.”

“Now just a damn minute!” chime in the Old Lefties, the Weavers were fine for a commercial folk group, but they grew out of the Almanac Singers, who were far more political and whose first recording was released way back in 1941, called Songs for John Doe, and whose Talking Union represented the kind of music the Weavers should have been performing but rarely did. “No Almanac Singers, and no Weavers! 1941-that’s when the real folk revival began.”

At this point the cultural historians kick in and argue that for all intents and purposes the folk revival actually began one year earlier, and not in Newport, Rhode Island or New York City, but in the Dust Bowl in 1940, at the end of the Great Depression, when Woody Guthrie released his landmark album Dust Bowl Ballads on RCA Victor. “No Woody Guthrie,” they argue, “and no nothin’!”

Now who discovered Woody Guthrie? A young folklorist named Alan Lomax, who dubbed him “the dust bowl balladeer” and recorded Guthrie for the Library of Congress Archive of Folk Song earlier that year, when Guthrie was just 28 years old. No Library of Congress Recordings, this argument goes, and RCA Victor would never have heard of Woody. And don’t forget Moses Asch, who earlier recorded Woody’s Dust Bowl ballads on the album Talking Dust Bowl, for his recently formed Folkways Records. “Thus,” this argument goes, “the Folk Revival begins with Woody Guthrie-and no Alan Lomax, no Woody Guthrie.”

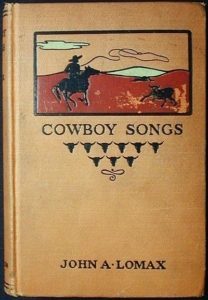

And it’s a fine argument, as far as it goes. Except that this young folklorist had a father, and his name was John Avery Lomax, and 30 years earlier, one hundred years ago this November, he published Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, with a handwritten preface by President Theodore Roosevelt, dated August 28, 1910. You may have heard of him; he’s on Mt. Rushmore.

Brothers and sisters, that’s a date to conjure with, because that’s when the folk revival began. And now that I have your attention brothers and sisters, John Lomax also discovered and recorded Leadbelly for the Library of Congress-in 1935, from which his son Alan got the idea five years later to record Guthrie.

But I came here to talk about cowboy songs. Welcome to the John Lomax Cowboy Songs Centennial-1910-2010. First published in November, 1910, Lomax’s first book became the template for future folk song collections-most of which would be published by either John Lomax, or later on by John and Alan Lomax, or still later by Alan’s younger sister Bess Lomax Hawes-about whom I have already written extensively and interviewed even more extensively in these pages (see accompanying links). It’s time to talk about the old man.

He was born in Goodman, Mississippi on September 23, 1867, and raised in central Texas. By the time he started teaching English at Texas A & M he had already collected the makings of a book of cowboy songs learned as a child growing up on his father’s farm fortuitously located along a branch of the Chisholm Trail. Tragically, however, his interest in these local ballads was condemned by his colleagues at the university as unworthy of serious study, and the gifted but impressionable budding scholar took it too much to heart: he burned his collection to please his critics, and tried to get over his early obsession with the songs he had learned directly from nearby ranch-hands growing up.

Fortunately for America, however, he could burn the manuscript but he couldn’t quite get the songs out of his head. When he later took a teaching fellowship at Harvard he finally met the two scholars who were worthy of his own talent: Professors Barrett Wendell and George Lyman Kittredge. When Lomax mentioned to them what he had done to his cowboy song collection and why he had done it they were horrified.

They told him he must do everything in his power to reconstruct the manuscript and then add to it by going around the country and completing his collection with firsthand interviews from his informants. They understood that these songs were the real thing-folk poetry of a very high order, and needed to be preserved, documented and if possible, recorded.

Lomax had found his calling. With a little money from Harvard and his own savings, he purchased a massive direct-to-disk recording machine that took up the entire trunk of his big black Ford sedan. He began to travel around the countryside asking the last of a disappearing breed of cowboys if they would sing their songs into his recording machine. What he discovered as he did so was almost as big a disappointment to him as the discouragement he had faced from his former colleagues: the cowboys themselves didn’t think their songs were worth preserving, let alone recording. To them they were just a way of passing the time as they herded cattle to market-to think of these songs as literature was beyond their ken. But this time Lomax would not be turned from his path-he kept at it, and because he did we now have such songs as Buffalo Skinners, The Chisholm Trail, the Dying Cowboy, Git Along Little Dogies, and Home On the Range. Eventually, Lomax brought his recordings to the Library of Congress for deposit in the Archive of American Folk Song, which was started by Robert Gordon, and of which Lomax would soon become director.

Despite the fact that he tended to be a conservative in his politics, and would eventually alienate even Leadbelly-whom he discovered in the Louisiana State Prison in Angola–with his ingrained sense of Southern paternalism towards African-Americans, there is no gainsaying the fact that Lomax regarded and recorded his black informants with the same dedication to preserving their art that he brought to white informants.

He was no progressive democrat in his views of social justice and reform, but on the larger question of an innate sense of respect for the folk poets from whom he drew forth his ever-expanding treasury of American folk song, he was a true believer. He insisted that any folklorist who traveled with him copy down the songs just as they were performed-without regard for taste or social mores-he wanted them preserved in their raw form, as gritty and real as the people who passed them on, even if he eventually would have to make some occasional compromises in what publishers would allow him to print. Scholars could sort that out later, he reasoned, but at the Archive of American Folk Song he wanted the unadulterated real thing on record for posterity. Thus, for example, Sweet Betsy from Pike would “make a great show for the whole wagon train,” in Pete Seeger’s cleaned up version on American Favorite Ballads (newly released on Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, which I recently reviewed in FolkWorks), whereas Lomax had originally heard her “show her bare arse for the whole wagon train.” (In his book, however, he omits the verse entirely.) By today’s standards even the rough-and-tumble version of the original gold miners seems rather sweet and quaint.

Once his cowboy song collection was published, Lomax turned his attention to Black American folk song, which he soon found was best documented in southern prisons and on chain gangs like the one where he would meet Huddie Ledbetter-Leadbelly-in 1934, the same year he and his son Alan published their first general collection American Ballads and Folk Songs.

In the meantime, MacMillan republished John Lomax’s first book, Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads in a much-expanded version in 1916, and yet again in 1924. Gold mining classics like Days of 49 and the aforementioned Sweet Betsy were sung alongside cowboy classics like The Gol-Darned Wheel, which both Sam Hinton and Glenn Ohrlin would later sing with gusto. And his son Alan’s protégée Woody Guthrie, with his singing partner Cisco Houston, would themselves record two albums of cowboy songs for Moe Asch’s Folkways Records.

John Lomax had to face and overcome the resistance of both academics and his own folk sources to save the very core of American folk song from passing into oblivion. He certainly had no way of knowing that many of these very songs some forty years down the road would become commercial hits and even light up the silver screen. That was not the point and would not have interested him had he been able to foresee the folk revival he started. He was an English professor, and to support his growing family a banker as well, to whom these songs were literature as worthy of study as the English classics on which he was trained.

John Lomax died in 1948, just one year before the Weavers were formed and would record the song Goodnight Irene, which Lomax had patiently transcribed and recorded from his most illustrious informant, Leadbelly, fifteen years before, and without whom we might never have been having this conversation. Leadbelly pleaded with Lomax at this same prison recording session, where he first sang The Midnight Special to him, to also take down a song Leadbelly had just written-to Governor O.K. Allen: “If I had you, Governor Allen, like you got me, I would wake up in the morning and set you free.”

Lomax made sure the Governor received his song requesting a pardon, and the gods of folk music must have been listening too, for Leadbelly was indeed pardoned-the only convict to have sung his way out of prison-not once, but twice.

More to the point, Leadbelly aspired to be a black singing cowboy, just like Gene Autry and Tex Ritter, both of whom would later record Goodnight Irene. Leadbelly even wrote his own cowboy song to try to get his foot in the door, When I Was a Cowboy Out On the Western Plains. (There was room for only one black singing cowboy in Hollywood, however, and that honor would go to Herb Jeffreys, lead vocalist for Duke Ellington’s orchestra, who made four westerns with all-black casts, including The Bronze Buckaroo.)

Leadbelly also loved to sing for children, I wrote in a poem about the two men,

And spirituals like Oh Mary and Meetin’ At the Buildin’-

His last concert was at the University of Texas in Austin

They’d come a long way since Lomax took him up to Boston

And introduced him to white audiences at Harvard U.

He made him dress like a field hand-with a bale of cotton too

Evoking the plantation world of the Old South

So Leadbelly smiled and sang and watched his mouth.

Talk about an odd couple-Lomax never understood the man

Who chauffeured him around in his shiny black sedan

And yet he knew this was the greatest musician he’d ever found

This was why he’d carried that heavy recording machine around

This was why he’d left teaching to become a ballad hunter

This was “America singing,” not some one hit wonder-

And this is why I love John Lomax, our greatest folklorist:

He gave us Leadbelly-the tallest tree in the forest.

—from Leadbelly and Lomax © 1999 by the author

Neither Lomax nor Leadbelly, who died of Lou Gehrig’s Disease the following year in December, 1949, lived to see the folk revival that was ushered in at the half century mark, built on the twin towers of a Louisiana Negro convict and a determined white Texan scholar, who had laid its foundations in 1910, when this southern gentleman wrote with a prophetic sense of purpose to the President of the United States, asking him if he would please recommend his new book of old cowboy songs to the reading public.

As if it was the most natural thing in the world for the president to take time out of his busy schedule to read this letter from a complete stranger, and give him an honest reply, Theodore Roosevelt wrote him back, from Cheyenne, Wyoming, on August 28, 1910:

Dear Mr. Lomax,

You have done a work emphatically worth doing and one which should appeal to the people of all our country, but particularly to the people of the west and southwest. Your subject is not only exceedingly interesting to a student of literature, but also to a student of the general history of the west. There is something very curious in the reproduction here on this new continent of essentially the conditions of ballad- growth which obtained in medieval England; including, by the way, sympathy for the outlaw, Jesse James taking the place of Robin Hood. Under modern conditions however, the native ballad is speedily killed by competition with the music hall songs; the cowboys becoming ashamed to sing the crude homespun ballads in view of which-Owen Wister calls the “ill-smelling saloon cleverness” of the far less interesting compositions of the music-hall singers. It is therefore a work of real importance to preserve permanently this unwritten ballad literature of the back country and the frontier.

With all good wishes,

I am

Very truly yours

Theodore Roosevelt

(transcribed by this author from the original printed handwritten preface)

Lomax dedicated the book to him:

TO MR. THEODORE ROOSEVELT

WHO WHILE PRESIDENT WAS NOT TOO BUSY TO TURN ASIDE-CHEERFULLY AND EFFECTIVELY-AND AID WORKERS IN THE FIELD OF AMERICAN BALLADRY, THIS VOLUME IS GRATEFULLY DEDICATED

The president, by the way, did not get his observations about Jesse James and Robin Hood from Lomax’s introduction; that was his own take on the outlaw ballad, and it is unthinkable in today’s politically correct world that someone in his position would-even at one remove-record a “sympathy for the outlaw;” it would never make it past the White House chief of staff. What an eye-opening reminder that we used to have leaders whose every public utterance was not field-tested by pollsters and advisors.

In a larger sense, it has been a long time since an American president has expressed a preference for folk song to popular music. But Theodore’s cousin-FDR-whose Hyde Park home was as far as possible from this untamed west, added his own support by mentioning that his favorite song was Home On the Range, first published in book form in Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads.

Both Roosevelts listened with their own ears and spoke with their own voices. The music that inspired them still inspires us today, one hundred years later. And the man who dedicated his life to preserving it for us is worth remembering too. Sing a cowboy song today, and a Leadbelly song too, for a sui generis American original, John Lomax.

Author’s note: Lomax’s first book was not the first book of cowboy songs published. That distinction belongs to N. Howard “Jack” Thorpe’s Songs of the Cowboys, published two years earlier in 1908, and including a number of songs and/or poems written by Thorpe himself. The original copy included 23 songs, among them most notably The Cowboy’s Lament, or Streets of Laredo. Unlike Lomax’s book, however, there were no tunes. Thorpe’s book, and its numerous subsequent editions including the excellent one I have from 1966, edited by Austin and Alta Fife (which includes a facsimile edition of the original), has recently been republished again by two modern cowboy musicians.

For my purposes, however, it remains a footnote in the story of the revival of folk music in the twentieth century. Whereas Lomax’s book looked to the future as well as the past, and led to Leadbelly, Woody Guthrie, the Weavers and beyond, Thorpe’s pioneering efforts never expanded to include folk music in general, but rather inspired generations of cowboy and old west re-enactors to museum period recreations of 19th century music, a worthy endeavor in its own right, but not my subject.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com. His Ph.D. is in modern literature. He has performed programs of cowboy songs, gold rush ballads and protest songs at the Autry Museum of Western Heritage. His Autry concert The Ten Greatest Protest Songs of the 20th Century, originally broadcast live on KPFK on September 26, 1999, was recently rebroadcast in their From the Vault series on the nationwide Pacifica network. It has just been released and is now available from Pacifica Radio Archives. Its catalog number is FTV 219.