Further on Flamenco

Further on Flamenco

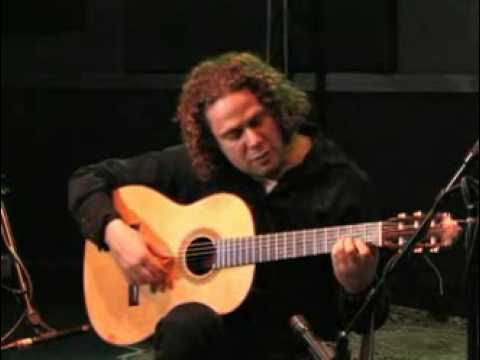

Adam del Monte drummed his fingers on the body of his guitar, following this with a couple of resounding pounds and then a series of rapid-fire dissonant chords. His furrowed brow framed by brown curly hair and his body bent over the instrument he cradled, the guitarist seemed to be in a world far away from the audience at the Souls on Fire concert at Valley Beth Shalom Synagogue last month. Yet his playing kept you on the edge of your seat.

Adam del Monte drummed his fingers on the body of his guitar, following this with a couple of resounding pounds and then a series of rapid-fire dissonant chords. His furrowed brow framed by brown curly hair and his body bent over the instrument he cradled, the guitarist seemed to be in a world far away from the audience at the Souls on Fire concert at Valley Beth Shalom Synagogue last month. Yet his playing kept you on the edge of your seat.

In the January 30 program, in addition to playing solo, del Monte performed with vocalist Pilar Morales, cajon player Geraldo Morales and dancer Lakshmi Basile. The communication among ensemble members seemed telepathic. Why were the musicians sometimes silent, other times playing passionately? Who was leading? The dancer’s arms would rise, undulating with fingers curved in different directions, like two serpents piercing the air. Then she would stamp out a rapid-fire rhythm and twirl in a split second, arms still raised, the fringes of her black shawl sliding over her face. The audience would burst into applause periodically while the musicians called out enthusiastically in Spanish. Suddenly the somber-faced dancer would stop and burst into a momentary smile, acknowledging the audience. Just as suddenly, she would turn away, grasp the skirt of her dress, and hike it up several inches to reveal her legs as she stamped out the equivalent of an extended trill.

What is this fascinating combination of dance, song, guitar, and percussive sound known as Flamenco? Associated with the Gitanos (the name for Gypsies in Spain) of southern Spain, it is by now a world-wide phenomenon. Perhaps this renown is all the more appropriate since the Roma (the preferred name for Gypsies outside Spain) have traveled so much of the world. While they brought their culture with them in their migration from Northern India between the ninth and 14th centuries, they absorbed outside influences. Both Moorish and Sephardic Jewish music influenced the development of their cante (song) in Andalusia. The cante jondo (“deep song”), which deals with themes of death, anguish, despair, or doubt, is thought to be the oldest form of Flamenco music. The Spanish guitar was adopted in the mid-19th century and became essential to the genre as did the baile or dance. The duende, a state of transcendent emotion is an essential element of traditional Flamenco. Rhythmic hand clapping (palmas) and encouraging interjections from the musicians (jaleo) add to the excitement as the ensemble performs in one of some 50 Flamenco music styles (palos) according to its particular compas (loosely defined- a complex rhythmic pattern).

Whether song, dance, or guitar dominate is a question that Flamencologists (yes, really) and musicians debate. Guitarist Adam del Monte experiences it as a kind of communion of artists. “People think that you (the guitarist) follow the dancer but really you follow the music itself,” he told me after his performance. “You follow whatever is unfolding at the moment. So sometimes (the dancer will) take the lead and I will follow her and sometimes she’ll create a space that will permit me to initiate something and that allows her to follow. So it’s a constant give and take.”

Whereas the performances originated in communities of Gitanos, by the middle of the 19th century, Flamenco had gained renown and found a home in venues known as cafes cantantes that offered ticketed public performances. Since then the Flamenco community has been beset by movements to commercialize it for tourist consumption and adapt it for other forms of musical composition such as operas. Flamenco companies have graced theater stages across Europe and beyond. But fortunately, Flamenco still shines vibrantly among groups of Gitanos who make music and dance informally as their ancestors once did in gatherings known as juergas.

Lakshmi Basile has danced Flamenco since childhood and has been performing and perfecting her art in Spain for several years. A San Diego native of East Indian heritage, Basile says that Flamenco dance exists in classical, contemporary/fusion, and Gitano styles. She finds the third the most compelling. “Gitano style of Flamenco is more earthy-looking, more grounded, more emotional, more expressive in the face. It can be simpler but it’s more dramatic. That’s different from a more modern Flamenco which is more technique-based and may have more movement and even fusions with other kinds of contemporary dance …Some people say classical Flamenco is the Gitano style, but others say it…has more influence from the folk dance of Spain –(for example) with the castanets. That could be considered more classical…The Gitano style is what makes me feels good in my body, what makes me say olé.”

Vocalist Pilar Morales, a native of Malaga in southern Spain, says Flamenco is as rooted in the culture of Andalusia as it is in the Gitano culture. “If you study about it, you’ll find that nowhere else in Europe do the Gypsies do Flamenco. Only in Spain. What does that tell you?”

Morales says that both men and women are accepted in the Flamenco vocal tradition and can produce the heart-rending quejido (cry) that comes from the depths of the soul. Sometimes, however, dancers prefer a singer of the opposite sex because this intensifies the male-female dynamic if the singer is expressing something about love. “Singers in Flamenco don’t perform a song per se,” she explains. “What we have is many different coplas (verses), and you pick and choose depending on what you want to express.”

A relatively recent addition to the Flamenco ensemble is the cajon, a square drum that originated in Peru. Playing cajon at the Souls on Fire concert was East L.A. native Geraldo Morales, who has studied the instrument in Spain and now plays with Flamenco groups across the country. “The percussion adds something to Flamenco, gives it more power, more drive,” says Morales of his role in the ensemble. “We’re improvising off the rhythm and feeding off each other. (At the same time) we’re following the dancer.”

Adam del Monte sees the inclusion of the cajon in the Flamenco ensemble over the past three decades as a mark of the genre’s continuing development. “That shows…how it integrates and absorbs different instruments of different colors and with time (this) becomes the new vernacular. And so the evolution of Flamenco is always taking place – rhythmically, harmonically, sonically, and even timbre-wise. You can take Flamenco to very contemporary realms where there is electric bass and flute and violin and trumpet. All that has already happened in Flamenco.”

Audrey Coleman is a journalist, educator, and passionate explorer of traditional and world music.