Cowboy Music of the Southern Hemisphere: Música Gaúcha

Winners of a 2022 Musica Gaúcha contest

Música Gaúcha, associated with the culture of the South American cowboy or cattle herder known as gaúcho, is the South American equivalent to Cowboy or Western Music. There are many shared sensibilities, including themes related to rural life, cattle and horse culture, even wide-open grasslands. Yet the music comes out entirely different – and not just because of the ubiquitous accordion in Brazil. In fact, so different that it takes two of us to write about it, but it makes for an interesting comparison. One of us did not know anything about it until recently (Roland), the other grew up playing this music in Brazil (Joana).

Música Gaúcha has a strong cultural significance in the southern regions of South America (Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina), where it is celebrated through festivals, gatherings, and cultural events. So much that “Gaúcho” these days refers to natives from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil’s southernmost state. Joana calls herself a Gaúcha despite never having wrangled cattle.

Os Serranos, a Música Gaúcha group, drinking their chimarrão (also known as mate elsewhere – a green tea-like beverage essential to Gaúcho culture) while performing:

Another, more grassroots, clip from this year’s Farroupilha Week, a weeklong event celebrated all over Rio Grande do Sul every September. This is Joana’s community group, the Orquestra de Violões de Gramado.

Farroupilha Week is named after the Farroupilha Revolution (or “Guerra dos Farrapos”), led by the gaúcho Bento Gonçalves. For an outsider, it is somewhat hard to grasp why it matters, seems like it refers to a 10-year separatist war (1835-45) against the Brazilian Empire that did not change anything. But for someone who grew up in Rio Grande do Sul, like Joana, the Farroupilha Revolution was a major history topic studied at school. Farroupilha Week remains a big event in southern Brazil where people dress up in Gaúcho garb (pilcha), there are lots of horses and parades, and everybody drinks chimarrão.

The accordion may be the most prominent instrument in Música Gaúcha, but a very sweet instrument that is much less known elsewhere is the viola caipira, a 10-string cross between a ukulele and guitar. Renato Goetten on viola caipira and friends play a medley of “5 clássicos da música Nativista gaúcha”:

Música Gaúcha has a number of different rhythmic styles that are present in songs from Rio Grande do Sul. Those sound nothing like Samba or Bossa Nova. Here is a webpage with videos that demonstrate different rhythms, the Milonga, Chamamé, Chamarra, Vaneira, and more. They speak Portuguese in the videos (scroll down, there is one for each rhythm), but you get the idea of the key elements.

Música Gaúcha is South American equivalent to the US Cowboy or Western music. In the US, Cowboy and Western music is now a smallish subgenre of country music. Until about 50 years ago, the music industry used the longer label Country and Western music, but it has now all been subsumed under the modern name, country music. Musically, these two music styles are entirely different. Culturally, there may be more similarities, at a minimum a rather romanticized view of the past.

John Lomax published a collection entitled Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads in 1910, followed a few years later by second collection Songs of the Cattle Trail and Cow Camp. Around that time, there was also a distinct literary Gaucho genre in Brazil. In the US, various musicians recorded western songs in the 1920s and early 1930s (we found no similar Brazilian recordings). Beginning in the 1930s, Hollywood took over with romanticization of the cowboy. Singing cowboys, such as Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, sang cowboy songs in their films and became enormously popular. That was the heyday of Cowboy music. Eventually that may have become the downfall of this genre because Cowboy Music became associated with kitschy movies that nowadays feel very dated.

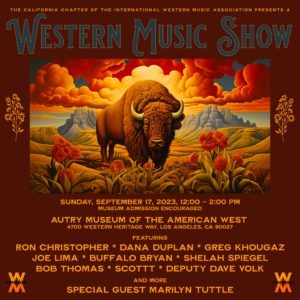

As a consequence, Cowboy and Western Music has shriveled to a fringe. There are still organizations supporting this music, like the International Western Music Association. And they have their events, including a regular show at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles.

As a consequence, Cowboy and Western Music has shriveled to a fringe. There are still organizations supporting this music, like the International Western Music Association. And they have their events, including a regular show at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles.

In contrast, the Brazilian anthropologist Ruben George Oliven believes that the cult of Gaucho traditions strengthened after World War II when Brazil became more urban and industrialized. He says that Gaucho Traditionalism was an urban movement that tried to recreate the rural values of the past. Unlike the decline of Cowboy Music and Poetry, Gaucho Traditionalism seems to have very strong grass roots support, with possibly two thousand Centros de Tradicōes Gaúchas (CTG). Joana says they exist in most towns, including the one in which she grew up. That also means a flow of new talent. Now an established musician, Renato Borghetti got his start at one of the many CTG. Nothing traditional, more of a shredder:

There is one communality between the US and the Brazilian cowboy styles that is absent in other styles: You get poetry and story-telling mixed in. Moreover, that is more contemporary poetry (i.e. these are not ancient or historical poems and stories, but recent or even improvised). In Brazil (and neighboring countries), there is a form of improvised poetry, known as payada. Those follow a fixed format of stanzas and are performed with guitar accompaniment. Rio Grando do Sul created (by state legislation) the Pajador Gaúcho Day on January 30. That date actually pays homage to the Gaúcho poet Jayme Caetano Braun as it was the date of birth. There also is a statue of him in Porto Alegre, the capital of Rio Grande do Sul.

Every state in Brazil tries to support their local cultural heritage, but Rio Grande do Sul seems to put particular effort into it, especially with the Centros de Tradicoes Gauchas that have events, dancing lessons, music lessons throughout the whole year. Also, there is pride in the characteristic “Pilcha” clothing, the Brazilian Cowboy outfit, and you can see them dressing in their Pilchas to go to work or just as their daily clothes depending on where you are in Rio Grande do Sul.