Cotten Picking Good

Cotten Picking GOOD

She taught herself to play guitar when she was 12 years old, a guitar she had earned with wages of 75 cents a month cleaning a white woman’s home in Chapel Hill, North Carolina; when she had been working for the better part of a year she got a raise—to a dollar a month.

She taught herself to play guitar when she was 12 years old, a guitar she had earned with wages of 75 cents a month cleaning a white woman’s home in Chapel Hill, North Carolina; when she had been working for the better part of a year she got a raise—to a dollar a month.

She sent the money home to her mother who asked her what she wanted for her birthday; “a guitar, mama,” she replied; so her mother went to the music store in town and found the guitar her daughter had her eye on all that time. The storeowner sold it to her for $3.75, and she went home and started practicing all day and well into the evening, “much to my mother’s sorrow,” she would later say.

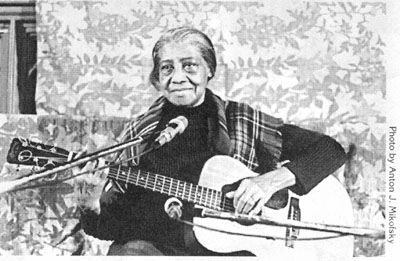

She wrote her first song that same year; you might have heard it; you might even have played it. It’s called Freight Train, and the young girl’s name was Elizabeth Cotten (January 5, 1895 – June 29, 1987). She invented her own way of playing guitar, because she was left-handed and it was strung for a right-handed player. She turned it upside down and started using her thumb to play the treble strings and her fingers to play the bass, reversing the usual method of finger picking.

It therefore came to be known as Cotten picking. It’s the first song I learned to play in finger-style guitar. The tune is so natural, so simple and so logical, it’s almost as if it was made for the express purpose of teaching someone how to fingerpick:

Freight train, freight train run so fast

Freight train, freight train run right past

Please don’t tell which train I’m on

So they won’t know which route I’ve gone.

When finger-style guitarist Jill Fenimore heard those lyrics for the first time she wondered if they might have been referring to the concerns of a runaway slave—almost like an Underground Railroad song rather than a modern train song. Her question makes sense of the song in a way I’ve never heard, one that frames it in a historical context that gives it extra poignancy and drama.

The story of how Elizabeth Cotten came to the attention of the public is one of the Ur-stories or creation myths of modern folk music. When she was 16 Elizabeth Cotten started working for another white family in upstate New York—Ruth Crawford Seeger, the second wife of Charles Seeger—Pete Seeger’s father. Ruth Crawford Seeger was the mother of Pete’s half brother and half sister—Mike and Peggy Seeger. She wasn’t there to play guitar, which nobody knew she could, but to do domestic work. One afternoon when her chores were done she got tempted by all the instruments hanging on the walls of their home, and pulled down a guitar and snuck it into the kitchen. She started playing her song, Freight Train, when Mike and Peggy arrived home from school. Drawn to the unusually melodic finger picking patterns coming from their kitchen they crouched near the door to overhear.

Suddenly Elizabeth realized she had been found out, and someone was listening to her play. Immediately fearful for her job she put down the guitar and apologized to Mike and Peggy for wasting time and assured them she would get back to work.

“Nothing doing,” they replied; “we want to hear what you were playing; where did that song come from?” “I made it up a few years ago,” replied Elizabeth, “listening to the freight train running by my window.”

“Please play it again,” insisted Mike and Peggy; and this time they watched as well as listened, and what they saw was more unbelievable than what they heard: their young housekeeper was playing the guitar upside down, with her left thumb picking the intricate patterns on the treble strings and her index and middle fingers playing the alternating bass notes—all with her left hand, while her right hand made the chords upside down on the neck.

“Why are you playing the guitar backwards and upside down?” they wondered. “I’m left-handed,” replied Elizabeth; “I didn’t know how else to play it. That’s just the way I picked it up.”

Mike and Peggy looked at each other in disbelief; it was hard enough to play the guitar the normal way; what Elizabeth was doing astonished them, and inspired their new name for how she figured out her unique style of guitar playing: Cotten picking. When she invented it there were no “left-handed guitars,” adapted to her needs; so she reversed everything she needed to do and played brilliantly in spite of it. Indeed, perhaps because of it.

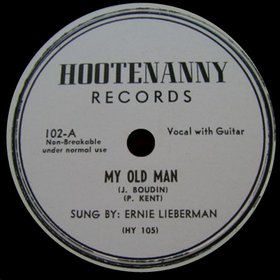

This I know because I too am left-handed, and when I first picked up a guitar to start playing it I naturally held it the same way Elizabeth Cotten held it, and blithely and ignorantly started strumming away. However, unlike Elizabeth Cotten I had a guitar teacher in front of me—a very good guitar teacher too—who was appalled at what he saw me doing. So Ernie Lieberman, who would later play with the Limelighters and Gateway Singers, insisted that I play right-handed, like everyone else or, he assured me, I would never be able to develop as a musician,

This I know because I too am left-handed, and when I first picked up a guitar to start playing it I naturally held it the same way Elizabeth Cotten held it, and blithely and ignorantly started strumming away. However, unlike Elizabeth Cotten I had a guitar teacher in front of me—a very good guitar teacher too—who was appalled at what he saw me doing. So Ernie Lieberman, who would later play with the Limelighters and Gateway Singers, insisted that I play right-handed, like everyone else or, he assured me, I would never be able to develop as a musician,

What did I know? I was twelve years old, the same age as Elizabeth when she had started, so I listened to my guitar teacher, and succeeded in becoming a very respectable if mediocre guitarist.

At the same time my teachers at school did their best to convert me into writing with my right hand as well, and succeeded in making my penmanship a thing of disfigured, mangled pen strokes, the envy of any medical doctor who has ever filled out an unreadable prescription.

I am convinced that if I had just kept playing guitar on my own, untutored and uninterrupted, I would have become a far better instrumentalist in the end. After all, it didn’t hurt Elizabeth Cotten. And it didn’t hurt Paul McCartney either. Or Jimi Hendrix; left-handers all; and my brethren.

The real irony of it, though, was that Ernie was a member of People’s Songs, a true leftist in the great radical American tradition; but when it came to being left-handed, I had to be converted into becoming a right-winger.

Ernie came from Brooklyn, and coached baseball too. It’s a good thing he never coached Sandy Koufax. (I’m kidding, of course; Ernie was my mentor.)

Southpaw Carl Hubbell was another member of my fraternity; and on a gray day in the All-Star game of 1934 threw his screwball and struck out five in a row of the greatest hitters of all time—Joe Cronin, Al Simmons, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Jimmy Fox.

Proud to be a lefty; I came along too late for the Meal Ticket, King Carl, but I got to see Libba Cotten once, in her 90th year, when lifelong friend Mike Seeger brought her out to McCabe’s during a farewell concert tour in 1983.

Proud to be a lefty; I came along too late for the Meal Ticket, King Carl, but I got to see Libba Cotten once, in her 90th year, when lifelong friend Mike Seeger brought her out to McCabe’s during a farewell concert tour in 1983.

Talk about a double bill: Mike was still her biggest fan, ever since his and Peggy’s serendipitous discovery of her playing guitar in their kitchen. He recorded her for Folkways, and introduced her work to better known artists like Peter, Paul and Mary, who first recorded Freight Train in 1963. That same year, when Libba neared 70, she began her professional career as a musician—long after most people had retired.

Fortunately for her other fans, Arhoolie Records released a record of performances from this tour—Elizabeth Cotten—Live; it won the Grammy in 1984 for “Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording.”

Let me tell you, dear Reader, it’s Cotten-picking good—both her songs and stories shimmer with the best that real folk music has to offer. Even at 90, her voice and guitar playing offer you a rare glimpse into the heart and soul of a great artist who could distill her whole life into a few brilliant lines:

Oh babe, it ain’t no lie

Oh babe, it ain’t no lie

Oh babe, it ain’t no lie

This life I’m living is very hard.

And looking back on sweeter times, she asks simply, “Didn’t we shake sugaree?” Her writing, singing and playing are completely unaffected—every note is there for a reason, and every word hits home. For its apparent sweetness quickly becomes bittersweet, as she concludes with: “Everything I had is gone.” Freddie Neil’s classic recording of Shake Sugaree demonstrates just how deeply Elizabeth Cotten’s songs affected the best performing artists of her time.

A quick guitar lesson.

When David Cohen—a bearded, gentle giant of a man and great guitar teacher—taught me to fingerpick nearly fifty years ago he chose that song to show me how, in the following progression. First go through the entire tune with just the alternating bass—no treble (or melody) notes at all. (The “C” position is the one most guitarists use, though Pete Seeger plays it in “D” chords on his 12-string.) The alternating bass is done with the 5th string, then 4th string, and then 6th string. Walk through all the chord changes, from C to G to G7, back to G to G7 to C, E7 to F, to C to G to C.

Then go through it the second time, adding just one (the index or middle) finger to pick out the melody. At this point you can avoid any syncopation—play the treble notes simultaneously with the bass notes.

Once you can play the entire song with just the alternating bass and one line of treble notes you can add syncopation by playing the treble line (still with just the middle or index finger) either just before the bass notes or just after; this basic pattern can then be varied during the song, sometimes syncopating the melody before and sometimes after the bass line.

Finally, you can add a second finger to the mix; I use my middle finger to play the top line of the melody on the first string, and then alternate with my index finger to play the second and third treble strings for either a drone effect or the descending notes that require those strings.

It actually sounds more complicated than it is, and the tune is so logical that your fingers will find the strings they need to pick out the melody. Some of those notes will be easier to play by using your left hand that is making the chords to shift one finger (first the index then the pinkie finger) to the first or second string, especially in the transition from E7 to F. To get precise instruction one can find tablature on-line, and work your way through the piece one step at a time. An excellent source of instruction for folk guitar is available from Happy Traum, who has his own web site.

If it looks difficult, bear in mind that Libba Cotten, as was said of Ginger Rogers in relation to Fred Astaire, did it all backwards, and on high heels!

1) Elizabeth Cotten. Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes. Smithsonian Folkways Records. (Includes best liner notes by Mike Seeger.) 1989.

2) Elizabeth Cotten. Shake Sugaree. Smithsonian Folkways Records

3) Elizabeth Cotten. Live!. Arhoolie Records, 1983;

4).Elizabeth Cotten. Vol. 3: When I’m Gone. Smithsonian Folkways Records

5) Legends of Traditional Fingerstyle Guitar. DVD Vestapol.

Smithsonian Folkways Artist Spotlight: Elizabeth Cotten

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com