CLASSICAL FOLKIES

Classical Folkies

Classical music, pay up! You owe a debt to folk music. I know you don’t like to hear that, but it’s true. Is that right, you declare smugly.

Classical music, pay up! You owe a debt to folk music. I know you don’t like to hear that, but it’s true. Is that right, you declare smugly.

What exactly do you mean by folk music?

Okay. This question has provided fodder for journal articles and panel discussions since “folk music” entered our vocabulary. For purposes of this column only, folk music means songs, dance melodies, and related storytelling and poetry produced eons ago by a person or persons known as Anonymous or Traditional. These musical creations change to some degree as they pass from generation to generation but retain their essential, recognizable character. This provisional definition rules out many beautiful folk-style pieces credited to specific authors such as Bob Dylan. Do you accept this definition, longhairs?

Grudgingly

Thank you.

As I was about to say, the classical repertoire of most Western nations includes art music based on a folk tradition. You longhairs enjoy listening to it in concert halls and playing it on classical music stations and sound systems. That word nation leads me to a brief foray into the historical context. (Liberal arts graduates having strong powers of recall may skip the next paragraph.)

Until the early 1800s, the word “nation” was not in general use because powerful clans with military might carved up and dominated the various regions of the continent. Here and there, philosophers quietly suggested the possibility of a political order that entitled populations to set their own borders based on common language and cultural heritage. These were musings, not calls to action. But the French Revolution showed that a massive popular uprising could change the political order. This and other influences spurred a wave of nationalism that swept across Europe. Roughly from the second decade of the 1800s through the end of the First World War and even beyond, the goal of nationhood gripped the popular imagination. Members of the middle-class intelligentsia vividly pictured a homeland unified by the people’s common language and culture.

What does this have to do with music?

Interrupting now, are we? All right. People involved in the literary and performing arts were riding on the nationalist wave. But where was the national culture? They identified it with “simple” peasants who lived in outlying areas, far from corrupting urban influences. They labeled these idealized residents of rural communities “the folk”. Their vivid tales, vibrant songs and rustic dances seemed to have passed, unchanged, from generation to generation. What a find! Scholars, musicians, and self-styled folklorists fanned out into the countryside, collecting and documenting folk performances in villages and towns. Incidentally, they did not consider remunerating or crediting the performers or local informants. Hungry classical composers drew upon this field research. They also explored the music of their own regions. The goal was to unearth sources of folk-inspired works that would fuel pieces for symphony orchestra, smaller ensemble, and voice. All right, spinners of art music. Does my contention that you have a debt to folk music begin to make sense?

Let’s hear a couple of examples.

Delighted. Consider the following folk music-laced compositions from regions of Spain and France.

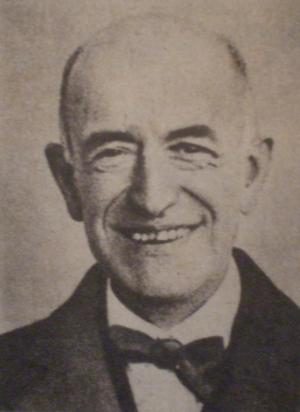

Manuel de Falla in 1919

Andalusian Soul

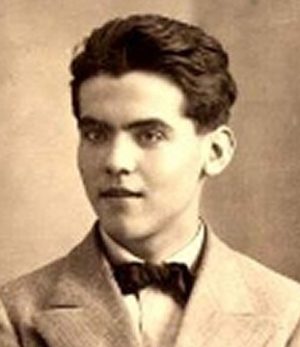

Federico García Lorca in 1914

Composer Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) and musically-inclined author Federico García Lorca (1898-1936), embarked together on a search for folk music in their native Andalusia. In their travels, they witnessed Andalusian villagers perform folksongs and dances that were part of their daily lives as well as those connected with special occasions. The pair also poured over the available songbooks of popular folk tunes. Like the composers mentioned above, they believed that this source could be a foundation for art music. However, they didn’t want to exploit folk music but to celebrate it in the classical genre. Each was inspired to arrange folksongs for the operatic voice. Falla’s Siete canciones populares españolas (Seven Popular Spanish Songs) is considered one of the most eloquent musical expressions of nationalism to come out of Europe. Lorca, for his part, found older Andalusian folksongs to be especially fascinating. They became the basis for his Canciones españolas antiguas (Old Spanish Songs) which often incorporated flamenco rhythmic and melodic figures. These two works influenced composers such as Basque Jesús Guridi and Catalan Xavier Montsalvatge to adapt folk music from their home regions for the concert hall.

My favorite recording features mezzo-soprano Teresa Berganza with nuanced guitar accompaniment by Narciso Yepes. Berganza’s voice expresses the vibrancy and profound simplicity of the Andalusian folksongs that inspired Falla and Lorca. Canciones españolas also includes songs from earlier eras.

Interesting.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2enib0lS2A

Nudge from a Nation

Even if the name Joseph Canteloube (1879-1957) and the Auvergne region of France are not on your radar, chances are that somewhere you have heard a sweet soprano voice wafting through the air, lingering on each phrase. A few instruments gently introduce the melodic line, then softly curl around the beguiling voice. Later, rich orchestral harmonies surge forth, underscoring the splendor of the imagined scene. While “Baïlero” may be the best known of the Chants d’Auvergne (Songs of the Auvergne), each of Canteloube’s 20-some songs carries its own distinctive mood.

Inspiration for this masterpiece came from the landscape and village life of the Auvergne, located in south central France, where the composer’s ancestral home. had stood since the eighteenth century. It is a region of rolling hills, low mountains, and vast oak forests. As a child, Cantaloube took long walks with his father, hiking along hill and mountain paths. They strolled through villages where the musically-inclined boy first heard folk songs that would enthrall him for the rest of his life. Among them were shepherd songs known as baileros.

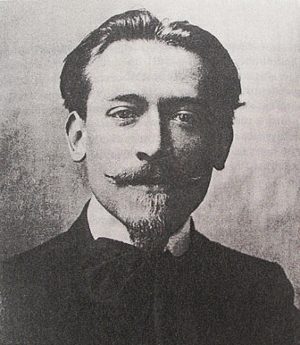

Joseph Canteloube

As a young man, Joseph Canteloube studied composition in Paris. There he became part of a circle of students who regarded French folk music as a springboard for their composing activities. This idea engaged them not only because they identified with the European nationalist movement but more specifically because of a project the French government had launched in the wake of the country’s humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). To restore national pride, the Third Republic harnessed the arts to demonstrate the beauty and cultural riches of France. The massive public program honored regional traditions in music, dance, and storytelling. Free concerts presented music by French composers. New musical works dedicated to the glory of France were meant to uplift the population. The program’s success over two decades spurred the government to perpetuate the model in the decades that followed.

The budding composer Canteloube encountered a folk-based musical masterpiece while working as a concert pianist and accompanist. Manuel de Falla’s Siete canciones populares españolas (Seven Popular Spanish Songs) often was on the requested repertoire. He well might have recognized it as a model for adapting folksongs into art songs.

I’m familiar with Canteloube, but what exactly did he adapt?

Based on a 1915 interview with the composer, Deborah Marie Steubing recounts the experience that inspired him to arrange “Baïlero.”

(On) a mountain above Vic-sur-Cère, in the Cantal (Haute Auvergne), Canteloube was sitting behind a rock, unseen by a shepherdess who sang out the call of this song… He then observed a shepherd on a faraway peak…(who) answered her very clearly. It was such a profound moment that Canteloube documented the entire song.

In 1923 the composer developed piano and orchestral settings for songs from the Auvergne region. By 1924 and 1925, for the first time, concert audiences were hearing his piano and voice arrangement of Chants d’Auvergne. The acclaim was immediate.

On record covers and sheet music for Chants d’Auvergne, following the title are the words “arranged by Joseph Canteloube.” Arranged, not composed. What better tribute to a classical work’s folk origins? My favorite recording features the late Victoria with the Orchestre des Concerts Lamoureux conducted by Jean-Pierre Jaquillat (EMI). Although many fine sopranos and mezzos have performed the Chants, for me de Los Angeles perfectly expresses the contrasting moods of the songs, from sparkling to whimsical, to amorous and languorous.

I’m close to convinced of our debt to folk music. But I’d like more examples.

We’re out of space here. How about I share some in a future column? I can give you examples from Finland, Czechoslovakia, the U.K., Hungary…

The United States?

A definite possibility.

By the way, how would we classical composers repay the folkies?

Hmmm. Let’s discuss it after that future column.

Audrey Coleman is a writer, educator, and ethnomusicologist who explores traditional and world music developments in Southern California and beyond.