Bread and Roses

The Bread and Roses Centennial: 2011

As we go marching, marching, in the beauty of the day,

As we go marching, marching, in the beauty of the day,

A million darkened kitchens, a thousand mill lofts gray,

Are touched with all the radiance that a sudden sun discloses,

For the people hear us singing: Bread and Roses! Bread and Roses!

As we go marching, marching, we battle too for men,

For they are women’s children, and we mother them again.

Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes;

Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread, but give us roses.

As we go marching, marching, unnumbered women dead

Go crying through our singing their ancient call for bread.

Small art and love and beauty their drudging spirits knew.

Yes, it is bread we fight for, but we fight for roses too.

As we go marching, marching, we bring the greater days,

The rising of the women means the rising of the race.

No more the drudge and idler, ten that toil where one reposes,

But a sharing of life’s glories: Bread and roses, bread and roses.

–James Oppenheim (December, 1911 The American Magazine)

Known first and foremost for his early protest songs, in particular for one great anthem, born in Minnesota, but who didn’t really make it until he came to New York City as an angry young man and had Judy Collins and Ms.Baez record his work, he remains an iconic poet to a whole generation of those still suffering, up against it, and committed to his ideals. May 24 is that groundbreaking American songwriter’s birthday.

I refer, of course, to James Oppenheim, author of the labor/feminist classic Bread and Roses, which was recorded by Judy Collins and Mimi (Baez) Farina, whose melody Judy Collins sang on her album of the same title, Bread and Roses.

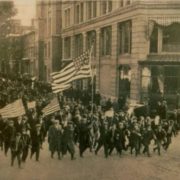

One hundred years ago, this December 1911, James Oppenheim published his classic labor poem in American Magazine. Within a month the poem had become famous in association with a mill workers strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Arturo Giovanitti, an Italian-American and member of the IWW, came to Lawrence to join a team of Wobbly organizers supporting the strikers—who were predominantly young immigrant girls— including Joseph Ettor, Margaret Sanger and eventually Big Bill Haywood, who had helped organize the Wobblies in 1905. Giovanitti wrote an Italian version of Oppenheim’s poem, Pan e Rose, based on a young girl’s picket sign inspired by Bread and Roses.

Then Caroline Kohlsaat set the poem to music so the strikers could sing it, and before you know it, Lawrence became indelibly known as The Bread and Roses Strike. Her tune is not especially beautiful, but it is strong and urgent, a marching song as befits the lyrics.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oYRcCa-ddOo

Sixty five years later Judy Collins wanted to record Oppenheim’s poem, but unaware that a woman had already composed music for it, she asked Mimi Farina to write a melody. Farina’s melody, due to its inherent charm, the power of Judy Collins’ reputation and the recording industry, has now become the melody of choice for most labor programs when it is performed, especially when produced by progressives who don’t value their own history—or her story either. Farina’s melody is frankly prettier than the original, which is why I prefer the original by Caroline Kohlsaat, and still sing it, just the way I learned it from Joe Glazer and Edith Fowke’s great songbook, Songs of Work and Freedom, published in 1960 and still in print, which gave Judy Collins and Mimi Farina sixteen years to have stumbled on it before Bread and Roses was recorded in 1976.

In recent years, not only composer Caroline Kohlsaat’s connection to the song, but even poet James Oppenheim’s has been slowly but deliberately eroded away by Jewish partisans of union activist Rose Schneiderman, most prominently associated with the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, which also observed its Centennial this year—March 25, 2011 (see my previous column—Triangle: The Fire Last Time).

As I describe in that tribute to poets and songwriters inspired by the Triangle fire, Rose Schneiderman is justly famous for her speech on April 2, 1911 at the Metropolitan Opera House in NYC, in the wake of the horrific fire just eight days earlier. Her verdict—We Have Tried You [Members of the Public] and We Have Found You Wanting—has replaced the jury’s verdict of Not Guilty as the consensus historical judgment.

But Rose Schneiderman is not justly famous for having said, “The worker wants bread, but she wants roses too,” not when this passage from a speech she gave in Cleveland the following year in 1912 is used to claim that she is the source for the title of Oppenheim’s poem, when in fact she was simply quoting from it.

I therefore challenge all of the various sources one now encounters on the Web—from Elyssa Barrett and Jeffrey Kaye in The Jewish Journal (“The Torah of Wisconsin—the Bread and Roses Edition”) to the Sinai Temple in Washington, DC, a variety of unnamed contributors to Wikipedia and pages of other misleading authorities who cite Rose Schneiderman as the source of the phrase Bread and Roses—every last one of them basing it on the same speech which when they bother to date it all invariably give it as 1912—to tell me how James Oppenheim managed to use it in his poem published in December of 1911. The critical date of his poem’s first publication is decisive in this case, in that to my knowledge there are no previous references to it in Schneiderman’s work—nor does she bother to use it in her great speech of April 2, 1911—We Have Found You Wanting—when she had a packed opera house hanging on her every word.

1911 was in fact James Oppenheim’s annus mirabilis, for in addition to publishing Bread and Roses he also published a landmark book of labor stories—Pay Envelopes–and a novel—The Nine-Tenths–based on the Triangle Factory fire, in which Rose Schneiderman’s entire We Have Found You Wanting speech, delivered in its aftermath, is quoted verbatim in the character of Sally Heffer, her fictional doppel-ganger.

And guess what: in a novel replete with quotes from Schneiderman, in which she is a major character and is shown speaking in situations both public and private, she never once utters the phrase (or any variant thereof) “Bread and Roses.”

Only when Oppenheim’s poem is published in American Magazine, in the last month of that storied year, does the phrase enter the vocabulary of the American working class—most prominently the following month, in Lawrence, Massachusetts, when on January 12 the mill-workers went out on strike.

Rose Schneiderman is never known to have used the phrase before it was widely quoted from Oppenheim’s poem, and the single quote that has been repeated as its source was not given until she made a speech in Cleveland later in 1912, when she clearly would have been borrowing it from Oppenheim, for by then it had been set to music by Caroline Kohlsaat and the Lawrence strikers had picked up the song.

It had also by then inspired an Italian song of the same title by Wobbly organizer, poet and translator Arturo Giovannitti, who was a participant in the Lawrence strike, and had seen it on the banner of young immigrant girls as Pan e Rose. But in opposition to the standard version of Oppenheim’s poem’s genesis, it did not derive from the banner; the banner was inspired by the poem. And so, at second hand, was Giovannitti’s poem.

But what was Oppenheim’s poem inspired by? The late Professor of American Studies Jim Zwick proposed a not entirely satisfactory hypothesis in the Winter 2003 Sing Out!, in which he unraveled the standard history of the poem which has been passed on as gospel to labor audiences for nearly a century, since 1915, when it appeared in Upton Sinclair’s massive anthology The Cry for Justice. The Gospel according to Sinclair was that the song’s title originated on the Lawrence strikers’ banner, saying “We Want Bread, and Roses Too,” to represent their demand for the ten hour day, with roses representing the time they wanted to be able to improve their minds, to read, to study art, poetry, in short to pursue a life of beauty and not mere survival.

What Sinclair did not realize at the time was that the poem was already in print when the Lawrence strike began on January 12, 1912, and that picket sign was lifted straight out of the poem. Utah Phillips, Judy Collins, even yours truly have therefore been circulating little more than a folk tale about the origins of Oppenheim’s poem—compelling, plausible, but wrong.

Zwick went back to the original publication in American Magazine, in December1911, and highlighted Oppenheim’s own attribution of the slogan to “the women of the west.”

More specifically, when the poem was first reprinted the following year on October 4, 1912, in The Public, a magazine in Chicago, their editor attributed the slogan to “Chicago women trade unionists.” Professor Zwick notes quite saliently that in 1912, Chicago was still seen from New York as, broadly speaking, “the west,” so there was no necessary contradiction between Oppenheim’s original attribution and the Chicago editor’s.

But Zwick does not stop there, and here is where he enters more murky territory. He goes on to observe that in 1907, Mary MacArthur of the British Women’s Trade Union League gave a speech in Chicago in which she attributed to the Qur’an the thought that “If thou hast two loaves of bread, sell one and buy flowers, for bread is food for the body, but flowers are food for the mind.” Zwick then speculates that her audience of Chicago women trade unionists could have reformulated (my italics) this into the slogan “We want bread, and roses too.”

And if ifs and ands were pots and pans, I’d be a baker. But I’m not, and Professor Zwick was still long on speculation and short on citations when it comes to tracing the source for Oppenheim’s signature poem’s title.

Perhaps the reference to the Qur’an is what led modern progressive Jews to want to credit Rose Schneiderman as the source for the slogan, Bread and Roses. For they too have found a religious basis for this powerful phrase—surprise!, it’s in The Talmud.* “The worker must have bread, but she must have roses too,” Rose Schneiderman, 1912. This quote, part of a longer speech, echoes a citation from the Mishnah “Im ein kemach, ein torah” (Where there is no flour (bread), there can be no Torah). What is Schneiderman saying about workers’ rights, and how does this connect to what the Mishnah is saying about the relationship between earning a living and studying Torah?

Note the all-important date for this quote: 1912, which clearly places it after the publication of Oppenheim’s poem, Bread and Roses, from December of 1911.

Nor is that the only unsubstantiated reference to a supposedly prior source for the phrase than Oppenheim’s poem; in one web site devoted to International Women’s Day, we find this choice little nugget: “On 8 March 1908, 15,000 women marched through New York City demanding shorter work hours, better pay, voting rights and an end to child labor. They adopted the slogan “Bread and Roses”, with bread symbolizing economic security and roses a better quality of life. In May, the Socialist Party of America designated the last Sunday in February for the observance of National Women’s Day.”

Well, New York City was Oppenheim’s home; his stories and poems of that period are set in New York, as is his novel The Nine-Tenths, which also recounts the garment workers’ strike of 1909 in great detail, beginning with Clara Lemlich’s Cooper Union speech which successfully urged the assembled audience to support a general strike, after seizing the microphone from Samuel Gompers timid counsel of caution.

And yet we are to believe that James Oppenheim somehow completely missed the 15,000 strong International Women’s Day march the year before which “adopted the slogan, ‘Bread and Roses’” and then mistakenly attributed it to “the women of the west” when he published his poem in 1911, the year of the Triangle fire.

Not bloody well likely. Search the Internet as I did patiently all day and all night and try to come up with a contemporary source for the assertion that “Bread and Roses” was “the slogan” for the 1908 International Women’s Day march in NYC, rather than yet one more attempt to rewrite fakelore into history from the perfect hindsight of a hundred years later, and you will come up, as I did, empty-handed.

Which brings me to the dog that didn’t bark, a reference to a Sherlock Holmes story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The story, and thus the mystery, hinges on Holmes pointing out to Watson, late in their investigation, “the curious incident of the dog in the nighttime,” which gives the story its title. Replies Watson, “But Holmes, the dog didn’t bark.” “That’s what was so curious,” concludes the detective. Had what was alleged to have happened actually happened, he implies, the dog would have barked.

James Oppenheim is my dog, and he didn’t bark. Had Rose Schneiderman or anyone else given a speech in NYC during the lead up to the 1909 garment workers’ strike in which she said the following, which Barrett and Kaye (and many others) quote from 1912,

only after the publication of Oppenheim’s poem:

What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist…The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.

Oppenheim would surely have given her credit, as he gave credit to “the women of the west.” Thus it is pure cant to say, as one web site on the history of Bread and Roses does that “Her phrase “bread and roses,” recast as “We want bread and roses too”, became the slogan of the largely immigrant, largely women workers of the Lawrence textile strike.”

Further, had the slogan of the International Women’s Day march in 1908 in NYC actually been “Bread and Roses,” he would likewise have been only too happy to assign them credit for the title of his poem, which he never claimed for himself. In short, he would have barked.

The fact remains that one hundred years after the publication of Oppenheim’s masterpiece of labor poetry we simply do not know the real source of the phrase “Bread and Roses.” What we do know is that, without his poem, and the song that came out of it, with music first by Caroline Kohlsaat , we would have forgotten it long ago.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com

On April 30 Ross will be down in San Diego, performing at the Roots Fest on Adams Ave., with sets scheduled for 12:00pm, 2:00pm and 4:00pm. On May 1, May Day, Ross will be honored by Sunset Hall at their annual Garden Party. Call 323-660-5277 or email wendy@sunsethall.org for tickets and information. On May 15, 4:30pm on the Railroad Stage Ross will perform at the 51st Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest and Folk Festival; and finally, on Tuesday evening, May 24, at The Talking Stick at 1411 Lincoln Blvd in Venice Ross will be hosting a 70th birthday party (in absentia) for that other Minnesota songwriter born on May 24, Bob Dylan, called: Forever Young: Bob Dylan’s Folk Years—1961-1964; $10.