BIOETHICS DURING THE INTERMISSION

Bioethics during the intermission

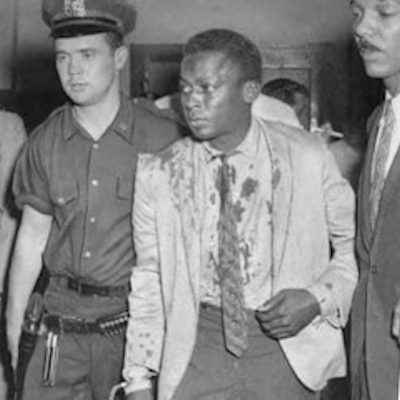

August 25, 1959. Eight days after the release of Kind of Blue, Miles Davis is beaten by police and arrested outside Birdland. Davis had just recorded a Voice of America broadcast — in other words, a broadcast for the armed forces — and was taking a break outside the club.

The name of this column is Intermission because I wanted it to reflect the kind of conversations we have together between sets or after the show. We do sometimes talk about music but not always, particularly as we get to know each other. So, I decided that during this Intermission, it might be a time for another topic that has come up more than once for me between sets or after the show.It starts something like this: “What is a bioethicist? What exactly do you people do?” So, my friends, given what has been going on in the world recently, I thought this would be a good topic for Intermission.

Etymology of the term comes from the Greek bios (life) and ethos (behavior). Following World War II, the Nuremberg trials brought to light the horrendous so-called “research” by the Nazi regime: The Doctors’ Trial. The Nuremberg Code, emphasizing voluntary consent and protecting human subjects from research injuries, arose from the judgment. Sadly, that lesson was not learned by those who conducted research on African American men from 1932 to 1972 who were never told that they were being studied just to see what happened if syphilis was left untreated: The Tuskegee Study. When this travesty finally came to light, legislation, and creation of a federal agency to oversee research followed: The Belmont Report

Philosophy professors Tom Beauchamp, PhD, and James Childress, PhD authored “Principles of Biomedical Ethics,” initially published in 1978 and now in its eighth edition. Their work is often considered the defining text of modern bioethics. As medicine advanced, so did the ethical challenges; Beauchamp and Childress’ ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice soon became the foundation of modern bioethics as a discipline. There are also alternate terms such as “medical ethics” and “healthcare ethics,” reflecting a broader scope of bioethics beyond research and the human body.

So, what does the world of bioethics look like today? Many bioethicists are in the world of academia in universities that have departments of bioethics/healthcare ethics, often within schools of medicine or philosophy. Legal cases, such as the one brought by the parents of Karen Ann Quinlan to allow disconnection of a ventilator due to her diagnosis of irreversible brain damage, brought bioethics issues to the mainstream media and, therefore, the general public. Cases such as this prompted the Joint Commission, a hospital accreditation entity, to require hospitals to have an “ethics mechanism” in 1992: AMA Journal of Ethics

I am not in academia and, although I do occasionally speak at colleges and serve on some hospital ethics committees, my primary focus is working to bring the “ethics mechanism” (which I like to refer to as an “ethics resource”) to locations outside academia and the acute care hospital. For the most part, for me, this means long-term care facilities which range from rehabilitation and immediate post-acute care to long term 24 hour care as well as home care and hospice.

What does this work look like? I think of it in terms of three general categories: education, mediation, and consultation. All of these in some respects help health care providers as well as those who receive health care services. I have provided education to doctors, lawyers, nurses, and individuals, some of whom are personally facing difficult health care decisions. Mediation is sometimes necessary when health care issues become highly charged and communication has broken down. Consultation involves not only making recommendations to individual providers and patients but also to health care institutions to aid them in policymaking where ethical concerns exist. These are situations that are addressed case by case and person by person, centering upon the individual who is personally affected by illness.

Finally, there is one of the four “pillars” of bioethics that I would like to discuss in more detail: Justice.

Over the past weeks, our entire nation has been awakened to the terrible injustices in the way that people of color have been treated by law enforcement. By the time that this is published, I hope that some positive steps have been made toward addressing this shameful consequence of systemic racism.

Bioethics calls for justice in health care as well. Although the US spends more than other “high-income” countries on health care, our population has a higher rate of chronic disease and suicide as well as lower life expectancy: Commonwealth Fund 2019 report. It is also well established that there are many disparities in health and health care in the US based upon race, ethnicity, age, disability, gender and socioeconomic status: Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief. There is no doubt that this uneven distribution of health care resources is the cause of a disproportionate amount of harm and death to people of color.

It is clear that our current health care system is unjust. It needs to be fixed. President John F. Kennedy said, in 1962 “We are behind every country, pretty nearly, in Europe, in this matter of medical care for our citizens.”: How Medicare Was Made. Sadly, this is still the case. Justice requires us to be better. Black Lives Matter in health care too.

Chris Wilson was the creator and co-producer of “Audiofile,” an award winning radio feature which ran internationally for 14 years on public and community radio. She is currently best known in the local folk community as manager for Irish musician Ken O’Malley. She is also an RN/Attorney/Bioethicist and publishes a blog addressing health care issues and seniors. You can reach her at chris@kenomalley.com.