ASK NOT: JFK 100

ASK NOT: JFK 100

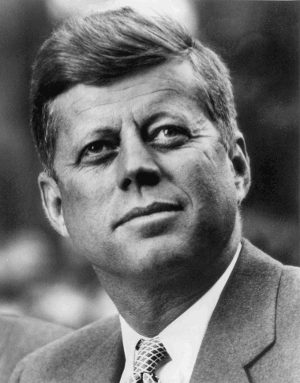

One hundred years ago this May 29, in 1917, John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, to Rose and Joseph Kennedy. His Centennial is this month. The JFK Presidential Library and Museum in Boston and the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC are holding events throughout the year in celebration. But so far did the reach of Kennedy’s inspiration extend that far smaller venues will be sponsoring tributes as well, including the Allendale Branch Library in Pasadena—Saturday, May 27 at 2:00pm. Terry Cannon is producing it for the library.

One hundred years ago this May 29, in 1917, John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, to Rose and Joseph Kennedy. His Centennial is this month. The JFK Presidential Library and Museum in Boston and the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC are holding events throughout the year in celebration. But so far did the reach of Kennedy’s inspiration extend that far smaller venues will be sponsoring tributes as well, including the Allendale Branch Library in Pasadena—Saturday, May 27 at 2:00pm. Terry Cannon is producing it for the library.

No doubt my small musical tribute to the 35th President of the United States will be little noted, nor long remembered—but that doesn’t faze me even a little. Somewhere JFK may notice, and that is more than enough for me. The purpose of my celebration is to highlight the folk music and artists who were similarly inspired by his life and legacy, from his role in World War II—where he served in the US Navy—to his 1,000 days in office as President, which overlapped with some of the singular events of the 20th Century, including the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Cold War, the Test Ban Treaty, and the March on Washington, the civil rights movement at its most noble, passionate and proud.

JFK remains a towering figure in the 21st Century, especially and perhaps even more so. During his foreshortened first term in office, its prestige was such that when his UN Ambassador Adlai Stevenson went to Paris seeking French President Charles De Gaulle’s support for the Cuban Missile Blockade, he carried with him a briefcase filled with photographs to document the presence of Russian missiles in Cuban waters, but (as reported by JFK’s speechwriter Theodore Sorenson) De Gaulle stopped him short with a wave of his hand and unprecedented response: “You don’t have to show me the evidence; if the President vouches for it, his word is all I need.” Stevenson never opened his briefcase. Those were the days when the President’s word was gold. Everybody—on both sides of the Atlantic—understood what truth meant, and the word “truthiness” had not yet entered our vocabulary, let alone “alternate facts.”

They were also the days when no one questioned the right of the people—as Dr. King put it in his “I Have a Dream” speech—“to protest for right.” Phil Ochs wrote Talking Cuban Missile Crisis and paved the way for many satirists to come. Bob Dylan wrote A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall and created a roadmap for future protest singers to follow. But on the same Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album, he also included this remarkable throwaway verse that engaged the living president in an imaginary personal conversation that put the president in a new light—not an adversarial relationship with a folk singer (that has pretty much held sway ever since), but a sympathetic cordiality that defined a new attitude:

My telephone rang and it would not stop

It was president Kennedy calling me up

He said, “My friend Bob, what do we need to make a country grow?”

I said, “My friend John, Bridget Bardot, Anita Ekberg, Sophia Loren: country’ll grow.

(I Shall Be Free—from Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, 1963)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_-VxMXEcYI

Alone amongst the new folk revivalists, Dylan made JFK a presence in his songs whilst he was still alive—before the assassination that immortalized him. That single verse has always put Dylan on his own plane to me—showing that there was no inevitability to a conflict between power and the people, which we have taken almost as a given ever since. The amicable, civil relationship between JFK and American folk artists like Dylan, Ochs and Dave Van Ronk was tantamount to FDR’s relationship to Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly and Josh White, all of whom also wrote friendly songs to president Franklin Delano Roosevelt—such as Guthrie’s Dear Mrs. Roosevelt, Lead Belly’s, We’re Gonna Tear Hitler Down, and Josh White’s The Man Who Couldn’t Walk Around.

JFK became the first president to invite a poet (Robert Frost) to participate in his Inauguration; Jackie invited two world-famous cellists to entertain at the White House, Pablo Casals and Gregor Piatagorsky, and JFK contributed an eloquent defense of the arts in general to the first book of essays introducing what would become the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. It was renamed in his honor after the assassination; before, it was known as the National Center for the Performing Arts. No president—with the possible exception of FDR and the WPA program that included so many writers—had reached out to artists in general in the way that Kennedy did. And it was Jackie, of course, who identified her husband’s administration with a Broadway musical after he died—Camelot, which had opened in 1960, just before he was sworn in.

Inspired by JFK, Bill Clinton invited Maya Angelou to read at his first Inauguration, and Lucinda Williams’ Arkansas father, poet Miller Williams to read at his second. And Obama, continuing in the same tradition, but redirecting it to include folk music, invited Pete Seeger (with Bruce Springsteen) to sing Woody Guthrie’s classic This Land Is Your Land at his first inauguration. And raising it to the next level, Obama invited Bob Dylan and Joan Baez—who was just inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame—to perform in the White House in a celebration of music of the Civil Rights Movement, including Dylan’s The Times, They Are A-Changin’, and Baez singing We Shall Overcome, as she had at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. Is it any wonder that a folk singer would rank JFK as the greatest president of the second half of the 20th Century?

But this view is no special pleading for folk music. It’s JFK’s leadership that brings it into sharp focus. He was the first president to make civil rights “a moral issue,” from his landmark June 11 speech before the assassination of Medgar Evers on June 12, 1963. That speech put the federal government clearly on the side of the marchers in the streets, against the police dogs and fire hoses in Alabama and Mississippi. On June 11, that same day, he sent Asst. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to confront Gov. Wallace in the schoolhouse door to integrate the University of Alabama with its first two Negro students.

It was JFK who launched the international Peace Corps and its domestic equivalent, Vista. And it was JFK who signed the Test Ban Treaty with the Soviet Union to lower the threshold of nuclear war—if anything could be said to have paved the way towards the end of the cold war, it was that rapprochement which put the president’s prestige behind his words that war was no longer thinkable—especially in light of how close we came in October of 1962 during the Cuban blockade, defused by a Soviet submarine commander.

All of these moments in modern diplomacy during the Cold War were accompanied by a soundtrack of antiwar songs and freedom songs, which became indelibly associated with his presidency—which prompted Sherriff Bull Connor to let the Freedom Riders go, because “I couldn’t stand their singing—and Marilyn Monroe singing Happy Birthday.”

But his public service began in World War II, when he piloted the PT 109 for the US Navy, so any portrait of the folk songs that tell his story for the Centennial must include Woody Guthrie’s The Sinking of the Reuben James on October 31, 1941, which prompted Woody to say to Pete Seeger, “Well, I guess we’re not going to be singing those peace songs anymore,” referring to the Almanac Singers album of songs opposing US involvement in the war. Both Woody and Pete would serve—Woody in both the Merchant Marines and the Navy, and Pete in the Army, stationed on the island of Saipan.

Pete’s 12-string guitar case proudly displayed a sticker saying “Veterans of Foreign Wars”: so much for those who mistakenly thought of him as a pacifist.

During his term in office JFK would stand up to the Soviet Union as no other president before or since—when he refused to allow Soviet missiles in our hemisphere. He challenged us to send a man to the moon before the end of the decade, thus putting his stamp on America’s greatest technological achievement of all time, on July 20, 1969.

And it all began with 17 words, next to FDR’s “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” the most eloquent line from any Inaugural address in the 20th Century: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” It prompted me to join SDS and CORE in the civil rights movement—and thousands upon thousands of young Americans to join the Peace Corps and Vista. It may have been the first and last time in my generation that a US President inspired civic engagement of the highest order.

And then, as I wrote in my song, That Dallas Morning, “in a flash it was over too soon.” Phil Ochs wrote the first elegy after the assassination on November 22, 1963, That Was the President. A couple years later he wrote The Crucifixion, an intense poetic meditation on the emotional impact of losing the youngest president ever sworn in: “So dance, dance, dance, teach us to be true / So dance, dance, dance, ‘cause we love you.”

Dave Van Ronk had a concert booking that evening, and called, when Walter Cronkite lifted his glasses from his nose and wiped his brow to announce the president’s death, to ask the concert promoters if they wanted to cancel, saying he would understand. To his surprise, they said “No, we want you to come anyway; this music now means more than ever.” Van Ronk, “The Mayor of MacDougal Street,” had a whole day to think about the song he wanted to sing in the president’s memory. It was a traditional song he had adapted with the help of Bob Dylan and Eric Von Schmidt, He Was a Friend of Mine. That became folk music’s eloquent eulogy to the slain president. And so it remains.

Saturday, May 27, 2017, 2:00pm at Allendale Branch Library in Pasadena, Ross Altman presents Ask Not: JFK 100; 1130 S. Marengo Ave, Pasadena 91106; (626) 744-7260.

Los Angeles folk singer and Local 47 member Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature from SUNY-Binghamton; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com