A MONTH IN PEÑA ALTITUD

A Month in Peña Altitud

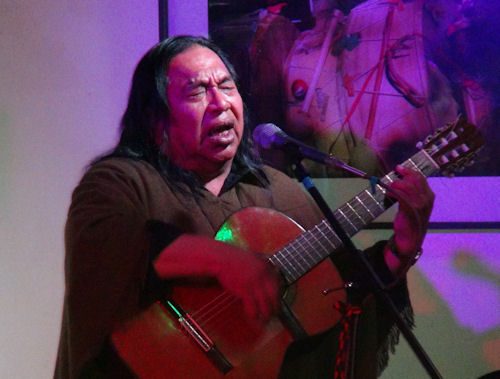

Musician and Peña Altitud proprietor Miguel Llave improvises on the Andean siku.

Until July 29, 2013, my clearest memory of Miguel Llave was witnessing him improvise on the quena surrounded by Andean slopes, the sound of the wooden flute rippling among the cliffs where we were hiking. My husband Michael and I had first met the multi-instrumentalist at his Peña Altitud, the folk music and jazz venue/restaurant located in the town of Tilcara, nestled in the Andes of northwestern Argentina. There Miguel hosts visitors enchanted by the sound of traditional Andean instruments, curious about Andean-jazz fusion and/or tempted by the unique cuisine of Jujuy province. Watching him play sets switching from saxophone to quena to siku (panpipes) of different sizes and tones to charango (a strongly resonating, lute-like instrument) during that Andean summer inspired my FolkWorks article of February 2012 titled “Musician of the Mountains.”

This past Andean winter (our summer) I returned to Peña Altitud alone as a graduate student in ethnomusicology to take a closer look at musical traditions in Jujuy province. Miguel had invited me to rent a room at the peña as a base for side trips to different pueblos. In the process, I encountered more dimensions of Miguel Llave as a musician, mentor, and cultural force in his community.

The hub of the action at Peña Altitud is Miguel’s first set, which he begins about a half hour after the place opens to diners, around 9:00pm (Argentines dine mid-evening). He almost always starts by playing saxophone to jazz classics, improvising over recorded instrumentals. When I first got there at the end of July, Miguel was so wracked by coughing fits from a nasty chest cold that I wondered how he could play at all. But his name is on the blackboard outside the entrance and it takes extreme conditions for him to abandon his date with the spotlights that hang from the peña ceiling. During the worst of the cold, his coughing diminished miraculously when he started to play.

It was only when he had to take a day and night off to get a chest x-ray in the provincial capital that other local traditional musicians pinch-hitted for him. I grew to recognize them because they appeared frequently at Peña Altitud, usually after10:00pm, sometimes playing with Miguel and other times performing on their own. Two were youngsters. There was Pablo Martinez, an eighteen year-old drummer who had been accompanying Miguel’s Andean jazz for two years. The kid was a walking percussion section, drumming his fingers rhythmically on the table and tapping his feet to music coming from Miguel ‘s solo set when he was waiting in the little room between the restaurant kitchen and the dining room. Another protégé, Franco Tonaba, had a set to himself later in the evening, starting with a dramatic entrance playing the erke, the horn made from about nine feet of joined bamboo canes attached to a cow’s horn. He would enter the dining room crouching and swaying as he blew the deep-sounding horn and swung it slowly over the heads of the diners. After that he would display his virtuosity on the quena, siku and guitar. Soon the late-night crowd would be up dancing past midnight to contemporized Andean music. It has occurred to me that the collaborative and generous way Miguel shares the spotlight with younger, less experienced musicians is the reverse of the “opening act” system so often used in the States.

Miguel is not only a mentor to younger musicians but also a mentor to an older one—me. During my recent stay, the first time I played the siku which I had brought from California (a product of Bolivia.com), Miguel told me its tone was substandard. He lent me a spare siku that had a deeper, richer tone and eventually I purchased it from him. To cure me of the involuntary throat sounds I made when playing, he taught me to take full breaths into the abdomen and open my throat. In order to get the column of air flowing properly, he recommended visualizing a point in the distance ahead of me and “blowing to it.” He pointed out subtleties of rhythm and accent in a Bolivian melody he taught me. I am also grateful to him for putting me in touch with musician Edgardo Nina who constructed a quena that had the holes sized and placed to accommodate my small hands.

Perhaps most important, Miguel shared with me that when he performs on the siku or quena, he pictures the Andean mountains he loves and plays to them and about them. When the weather wasn’t too cold–which was about half my stay–I would practice my instruments on the porch of the hut that was home for four weeks and gaze at the mountains that rose beyond the roof of Peña Altitud.

By the way, the cold days were especially appropriate for enjoying regional dishes on the peña’s menu. I became fond of llama stew (and they pronounce it jama), a seasoned corn puree called humitas, and a hearty mixture of meat, squash, hominy and onion known as locro.

Folk singer Tomás Lipán is a frequent guest performer at the peña.

Every few months Miguel features one of the most beloved folk singers of Jujuy, Tomás Lipán, whose songs often refer to the mountainous region the two musicians love, known as the quebrada. On August 23, his generous set propelled folk dancers to their feet waving handkerchiefs in the sensuous chacarera. Soon the more experienced dancers were pulling others, I among them, to the floor. Miguel welcomes the different energy Tomás brings to Peña Altitud and Tomás always plays generous sets, at the end alternating between dance-oriented numbers and fervent vocal pieces.

Usually towards the end of his second set, Miguel talks to the audience about the rich indigenous cultures that existed before the Spanish conquest and that have lived on in musical instruments, melodies and celebrations of the agricultural cycle that paralleled the Spanish-imposed Catholic calendar of observances.

From his father’s side of the family, Miguel is Aymara, one of the two most populous indigenous ethnic groups in the region, the other being Quechua. In my first visit to Peña Altitud, I thought the multi-colored checkered flag hanging over the entrance and the cloth with the same design hanging behind performers on the platform were simply a vivid decorative touch. On this visit, I learned that the colors have spiritual significance in the Aymara culture: White stands for mental reflection, green for the produce of the earth, orange for society and culture, yellow for energy, red for the earth, purple for politics, and blue for cosmic space.

Percussionist Pablo Martnez, vocalist-multi-instrumentalist Julio Herrera and vocalist-multi-instrumentalist Franco Torlaba take their turn in the spotlight at Pena Altitud.

When I asked Miguel about his purpose in addressing the audience, he responded, “More than anything, I want them to understand the place they are visiting. Argentina is extremely diverse. You have Buenos Aires (which is) very European and, in contrast, a province like Jujuy and the quebrada with its strong Andean influence and (its own diversity). There is not much information disseminated about the culture here and what comes from the government is often colonialist in tone. They speak of Indios as if (indigenous peoples were of one culture). They (ignore) the scientific knowledge and inventions that indigenous cultures amassed long before the arrival of Europeans…(The audience needs to understand) the value that these ancient cultures placed on the land, and that they should respect the land and not contaminate it.”

Many Californians I know would agree with Miguel when he tells his audiences that we are at a point where either the land is irrevocably destroyed by suicidal attitudes and actions or we change our way of thinking to one which is more collective and protective of the land. Several times I noticed members of the audience squirming after Miguel had been speaking for a few minutes, but after he concluded there was always enthusiastic applause.

Today I am back in summertime Southern California. I can’t say I miss wearing four sweaters under my jacket, leggings under my jeans, and two pairs of socks in my Reeboks. But I miss the world of music that I inhabited for a month in northwestern Argentina. Still, when I play my siku and quena, I follow Miguel’s lead and picture the mountains that rise beyond the roof of Peña Altitud.

Audrey Coleman is a journalist, adult educator, and graduate student in ethnomusicology at the University of California, Riverside.