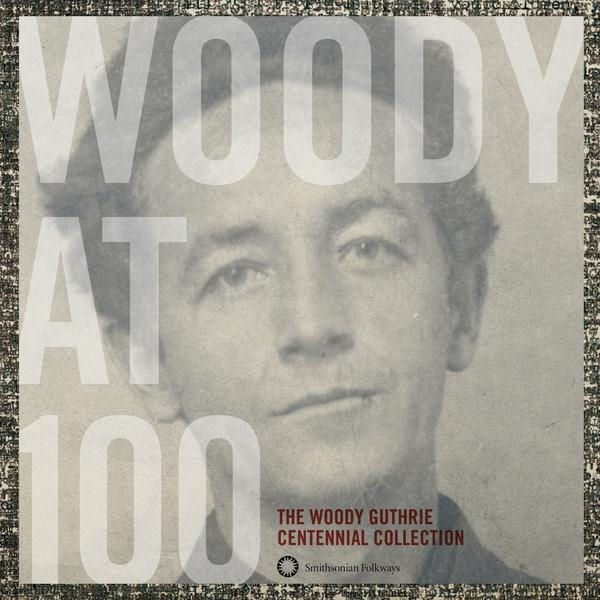

WOODY AT 100 – THE WOODY GUTHRIE CENTENNIAL COLLECTION

TITLE: WOODY AT 100: THE WOODY GUTHRIE CENTENNIAL COLLECTION

ARTIST: WOODY GUTHRIE

LABEL: Smithsonian Folkways

RELEASE DATE: 2012

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF AMERICA’S GREATEST FOLK SINGER—1912-2012

Saturday, July 14, 2012 would have been Woody Guthrie’s 100th birthday. To celebrate, something wonderful this way has come. This is the one you’ve been waiting for; the definitive monument to a diminutive giant—Smithsonian Folkways Centennial Collection of the Dust Bowl Balladeer’s recorded legacy drawing from both Library of Congress and Moses Asch’s Folkways Records, as well as other more obscure sources, with a hundred and fifty page coffee table-size book of photographs, paintings, illustrations, artifacts and manuscript excerpts of Woody Guthrie’s songs, prose writings and memorable epigrams such as, “Take it easy, but take it!”

Saturday, July 14, 2012 would have been Woody Guthrie’s 100th birthday. To celebrate, something wonderful this way has come. This is the one you’ve been waiting for; the definitive monument to a diminutive giant—Smithsonian Folkways Centennial Collection of the Dust Bowl Balladeer’s recorded legacy drawing from both Library of Congress and Moses Asch’s Folkways Records, as well as other more obscure sources, with a hundred and fifty page coffee table-size book of photographs, paintings, illustrations, artifacts and manuscript excerpts of Woody Guthrie’s songs, prose writings and memorable epigrams such as, “Take it easy, but take it!”

There are two recorded versions of his greatest song, This Land Is Your Land, demonstrating once and for all that it did not spring fully formed from the forehead of Zeus, but was written, composed, and revised, the way any master poet would be expected to work, until Woody arrived at his six gemlike verses and classic chorus—that is now a sacred text in the wide world of American folk music. To those who still regard this unofficial national anthem (just the way Woody would have wanted it) as having been censored the editors of this magnificent book-set (to call it a “boxed-set” understates their achievement) finally dispose of this shibboleth; Woody himself never recorded all six verses—and the Smithsonian did not release what they now refer to as the “standard recording” until 1997, long after these extra verses had already entered the folk canon through the inestimable efforts of both Arlo Guthrie (to whom Woody taught them as a child) and Pete Seeger. Pete (and Bruce Springsteen) sang every one of them on the National Mall during the inaugural ceremonies for Barack Obama in January 2009; if that be censorship, let me have more of it. What makes this collection a feast for the eye as well as the ear is that their book contains a full page photo reproduction of Woody’s original master recording—with the matrix number MA-114. Indeed, the size of the book almost perfectly matches the dimensions of an LP record sleeve—a beautiful touch!

What will call this book’s attention to even serious collectors of Woody Guthrie’s previously available work is its plethora of documents reproduced nowhere else—taken directly from the deep vaults of the Woody Guthrie archives in NYC; from which his daughter Nora Guthrie has been excavating unrecorded lyrics for the better part of the last two decades—and having them set to music and released by a variety of musicians from both the folk and rock worlds. For this project they have gone back to the source—and been able to include 21 of Woody’s previously unreleased performances and six never-before-heard original songs. What an amazing accomplishment considering he died October 3, 1967, 45 years ago!

This richly illustrated text is perfectly in keeping with the way Moses Asch always produced his original Folkways records—the accompanying soft-cover booklets inserted in the record sleeves usually had the lyrics to all the songs on the record, illustrated with wonderful images from Moe’s private collection. Folkways Records was a singular achievement of an artist/scholar/recording engineer who was committed to fully documenting the folkways of the world—with both sound recordings and accompanying texts and visual records of the artists he included in his vast catalog. How proud Moses Asch would have been of this testimonial not just to his greatest artist—Woody Guthrie—but also to the man—Moses Asch—who recorded, documented and preserved his work during the hardest of hard times.

This is a Folkways Record in the great tradition created by Folkways visionary founder. If PBS American Masters series is looking for a worthy new subject they need look no further than Moses Asch.

The editors and annotators of Woody at 100: The Woody Guthrie Centennial Collection—Jeff Place (archivist for the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage) and Robert Santelli (Executive Director of the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles)—have done a brilliant job of telling the stories behind Woody’s great songs—both their narratives and the full background of the recording sessions themselves. They also revel in the wonderful details of Woody’s songwriting craft, even telling the story of how he wrote The Ballad of Tom Joad on a borrowed typewriter—which Woody was too shy to ask for—so he delegated that task to Pete Seeger, who came through. And then they reproduce Pete’s tale of seeing Woody with a half-gallon jug of wine in the late evening, when he set out to retell the story of Grapes of Wrath, and finding the bottle nearly empty when Pete woke up in the morning and discovered Woody curled up asleep underneath the typewriter table, with the 17 verse ballad complete on several pages laid out next to it.

They did leave out one charming codicil to the published record—which Bob Santelli shared at a recent memorable evening interviewing Arlo Guthrie at the Grammy Museum’s oral history project—to which the public was invited. Santelli told of how when John Steinbeck first heard Woody’s song on an RCA Victor record of Dust Bowl Ballads he wrote a mock angry note to Woody saying essentially, “Fuck you! You captured in seventeen verses what it took me 250 pages to write!”

Another unexpected and previously unknown delight of this three CD collection is a section called “The Los Angeles Recordings,” including two songs never before heard:

Them Big City Ways and Skid Row Serenade. When Woody lived in LA he often stayed out at Will and Herta Geer’s home in Topanga Canyon, which is now the site of the Theatricum Botanicum. Woody had his own shack out there, on which he hand-painted “Woody’s Shack.” But Woody also liked to hang out on Skid Row, and picked up some tips singing in their bars.

It was outside one of those bars that vocalist Rose Maddox first heard Woody sing a song he called Reno Blues, about a cowboy who shot a lawyer in an argument over his girlfriend. She and her brothers recorded the song in 1949—as The Philadelphia Lawyer—and it became a certified regional hit. Here is Woody’s original recording from April 19, 1944.

There is one track that reveals how difficult and daunting this project must have been to sort through and piece together—the song Hard Travelin’, a harrowing montage of the many different kinds of hard labor Woody came across and may even have tried his hand at. The notes to the song credit Woody for mandolin and vocal, Cisco Houston for guitar and harmony vocal and harmonica virtuoso Sonny Terry for mouth harp. But listen to the performance (recorded in 1947, Smithsonian acetate 2767) and you won’t hear a mandolin, or harmony vocal, and the only harmonica accompaniment comes between the verses—cleanly separated from Woody’s vocal. Nor, when you listen to the harmonica, do you hear any of Sonny Terry’s signature whooping, note-bending and instantly recognizable grace notes between the main melody-line; no, I’m afraid no one would confuse Woody Guthrie’s cross-harp solos (held together on a wire rack around his neck so both hands could play guitar) with Sonny Terry’s. Woody taught Ramblin’ Jack Elliott to play like this; and Jack taught Bob Dylan.

But Woody did record Hard Travelin’ with this ensemble; if you want to hear that version (recorded in 1944, Master 689) you will need to get Rounder Records 2009 boxed set, My Dusty Road: Woody Guthrie (previously reviewed in these pages). You won’t mistake Sonny Terry’s brilliant harmonica accompaniment—woven throughout Woody’s vocal—for anyone else’s. And yet, oddly enough, if I had to choose between them, I actually prefer Woody’s elegant solo version, which I recall with deep fondness from one of my first really treasured folk recordings—Stinson Records Folksay series. You can see their stunning record cover art in this Centennial Collection from Smithsonian Folkways. This version of Hard Travelin’ is one of Woody’s purest performances—as close to perfection as one could imagine.

The song that Woody once called his “favorite song,” Hobo’s Lullaby, was not one of his own 3,000 compositions, but was written and recorded (in 1934) by his friend and fellow Merchant Marine Goebel Reeves (1899-1959), “The Texas Drifter.” In their notes to Woody’s 1944 recording, Jeff Place and Robert Santelli do an outstanding job of correcting the public record and giving Reeves the credit he deserves.

The separate and complete discography in this monumental achievement is the work of Texas librarian and Guthrie Scholar Guy Logsdon and includes all of Woody’s known recordings. Considering that his primary creative period—before showing the first debilitating signs of the inherited genetic illness Huntington’s Chorea—lasted about a dozen years it is remarkable how many recordings there are. This book devotes several pages to recreating the beautiful album covers (in miniature) of all of them, and lists their recording background as well. Jeff Place and Robert Santelli sample some of the rare treasures preserved in Smithsonian Folkways archives, including a number of radio programs Guthrie either hosted or appeared on (such as a series hosted by his friend Huddie Ledbetter, Leadbelly.) That is what sets this book-set apart from even the best of previous Guthrie boxed sets: the chance to hear Guthrie in an informal setting of a radio broadcast, talking and singing both—including a show broadcast on the BBC during WWII. It is unlikely that even rare records collections would have these broadcasts—and Smithsonian Folkways generously includes three of them.

Even more rare is a short recording on acetate that Moe Asch was able to capture of a live “People’s Songs Hootenanny” from one of their rent parties to raise money for their fledgling organization. During this Hoot Woody and Lee Hays (a founding member of the Weavers) have a wry debate that captures their wit and Midwest, Dust Bowl roots (Hays came from Arkansas, Woody of course from Oklahoma). Two songs came out of this recording—Ladies Auxiliary and Weaver’s Life.

For Angelenos, social and music historians, and Woody Guthrie fans alike, however, the most intriguing and revealing section of this book and record may well be the aforementioned four tracks entitled, The Los Angeles Recordings—with a separate essay included by Peter LaChapelle. That is because they are the oldest known recordings of Woody Guthrie—which he made himself in 1937 (though LaChapelle believes they may have been recorded as late as 1939) on a Presto disc-cutting machine.

Woody was just 25 years old at the time and one of a hundred thousand Dust Bowl refugees who had made it to Los Angeles. (For comparison, he was 27 when he made his famous Library of Congress recordings in 1940 with folklorist Alan Lomax.)

The way in which these LA recordings came to light is an “only in LA” story if I ever heard one. They were donated to the Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research—a private nonprofit library in South Central LA that specializes in local progressive history and culture distinguished by many donations of lifetime primary resource collections from major LA activists and artists such as Tom Hayden and Harry Hay—the gay organizer who left them his priceless Woody Guthrie acetate masters. Peter LaChapelle was a young graduate student in 1999 when he came upon them through the middleman in his search for source materials for his dissertation on the connections between the Dust Bowl migration and country and folk music. The middleman was Harry Hay and Woody Guthrie’s mutual friend actor Will Geer—Grandpa Walton of the TV series.

Their connection is opaque but worth adding to the scenario that Mr. LaChapelle weaves as to their background; start with the question how did the most prominent gay activist (founder of the Mattachine Society—the earliest gay rights organization) who was at the same time a member of the Communist Party Harry Hay wind up with these rarest of rare recordings? Will Geer’s daughter actress Ellen Geer is on record as believing that her father’s homosexuality is what broke up his marriage with Herta Ware. (Full disclosure: This reviewer was friends with both of them as a child, and spent many happy Sunday afternoons playing folk music on their front porch.) I see no reason to put Will Geer back in the closet; he and Harry Hay became lovers in 1934 while working in the Tony Pastor Theatre, and Hay credited the ten-years older Geer with being his political mentor as well. (They were also both involved in the San Francisco General Strike in 1934.) Will Geer is the narrator on the 1956 Folkways album Bound for Glory: Songs and Stories of Woody Guthrie. I therefore assume that it was Will Geer who was the immediate source of Hay’s becoming their owner.

To his enormous credit, Harry Hay knew how important they were and where they belonged, and when he donated his profoundly important historic document and record collection to the Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research included Woody’s original masters. Now they belong to the Smithsonian and therefore to the world.

We can only be grateful to Smithsonian Folkways for carrying on this incredible legacy of Woody Guthrie’s music and art—including a full-color portrait of Abraham Lincoln I had never seen before. This Centennial Collection is such a multi-faceted jewel it cannot fully be appreciated in one sitting. One will come back to it again and again to discover facets only glimpsed the first time through. As full and complete as it is, moreover, the book’s magnificent scholarly apparatus includes many avenues for continuing research and artistic pleasure at the end; for they do not hesitate to cite and credit other record companies who have contributed to making Woody’s work available, such as Rounder, Vanguard and most notably, Stinson.

When Woody wrote “From California to the New York Island” he wasn’t kidding, and this Smithsonian Folkways book finally demonstrates—for the first time, really—just how crucial California in general and Los Angeles in particular—was to the artistic growth of the Dust Bowl Balladeer.

When Woody Guthrie rambled round and noted,

The peaches they are rotting

They fall down on the ground

There’s a hungry mouth for every peach

As I go rambling round

he was standing on our good earth. Though he eventually wound up in the Big Apple, his artistic and political conscience was forged right here, amongst the most down-and-out of LA’s skid row. Perhaps that is why, before the painful throes of his final, terminal illness confined him to Brooklyn State Hospital for seventeen years, he found himself heading back here to renew old friendships with onetime comrades like Cisco Houston, Will Geer and Harry Hay. With all the roads that Woody traveled down, he started on Highway 66, heading out of the Dust Bowl and into “that old Peach Bowl, California!”

Thanks to Smithsonian Folkways Recordings we can now travel those roads with Woody, and see 150 pages full of the unforgettable things he saw and hear 57 of the wonderful songs he wrote. It’s a trip well worth your time. Note: Single tracks or the entire collection can be downloaded at the Smithsonian-Folkways website. Check out the Woody at 100 events and other Woody Guthrie information and links.

Happy 100th Birthday, Woodrow Wilson Guthrie.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com Ross Altman and author Peter Dreier will be doing a tribute to Woody Guthrie at the Allendale branch of the Pasadena Public Library on Saturday, September 15, 2012, from 2:00 to 4:00pm. Free and open to the public