Willie Nelson’s America

Willie Nelson’s America

In Concert at Bridges Auditorium

Pomona College, Claremont

February 28, 2013

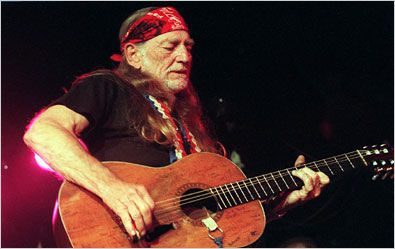

As long as Texas doesn’t take Willie Nelson, let them secede I say. He had the Lone Star State flag as his lone backdrop at Bridges Auditorium in Claremont (“Land of Trees & PhDs”) tonight—where he was greeted with a standing ovation before he even picked up his guitar named Trigger—after Roy Rogers’ horse. “This is my horse, that’s why I call him Trigger,” he said once, and Martin picked it up and put it in the best print ad they ever did. If more music has ever come out of one guitar I have yet to hear it.

As long as Texas doesn’t take Willie Nelson, let them secede I say. He had the Lone Star State flag as his lone backdrop at Bridges Auditorium in Claremont (“Land of Trees & PhDs”) tonight—where he was greeted with a standing ovation before he even picked up his guitar named Trigger—after Roy Rogers’ horse. “This is my horse, that’s why I call him Trigger,” he said once, and Martin picked it up and put it in the best print ad they ever did. If more music has ever come out of one guitar I have yet to hear it.

He put on one amazing show for the students “of all ages”—who gave him an even longer standing ovation at the end of his show. And then—guess what—he stuck around for another hour plus to sign autographs in front of the stage—everything from albums to T-shirts to cowboy hats to whatever they put in his weather-beaten hands. I have never witnessed anything quite like it from an artist of his stature—Willie is the real deal—he never strikes a false note—in person, in print, on film or on record; you don’t have to ask “what was that song?” It’s in your DNA, from Whiskey River, to Crazy, to Funny How Time Slips Away, to Always On My Mind, to Night Life, to Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground, to On the Road Again. It’s the soundtrack of America for the past fifty years.

But he didn’t just stick to his own songbook: he did a heartfelt tribute to the late Waylon Jennings, of “Waylon, Willie and the Boys,” including Good Hearted Woman in Love With a Good-Timing Man and Ed Bruce’s Mamas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys; and a sustained tribute to Hank Williams—who died 60 years ago this past January 1—including Move It On Over, Hey, Good Looking, and Jambalaya, and came back to Hiram Hank at the end, with I Saw the Light.

He also did a lovely set of American standards, with Hoagy Carmichael and Stuart Gorell’s Georgia On My Mind (which he played at Ray Charles’ funeral in 2004) and Irving Berlin’s 1936 Let’s Face the Music and Dance, from Willie’s album Stardust devoted to The Great American Songbook.

Other brief tributes included Steve Goodman’s City of New Orleans (title song of one of Willie’s albums), Kris Kristoffersen’s Help Me Make It Through the Night, Billy Joe Shaver’s No Need to Treat Me This Way and the 1945 Fred Rose classic Blue Eyes Crying In the Rain, which Willie made into a hit after moving back to his home state Texas in 1973, where he and Wayon Jennings became known as the Outlaws, and proved you can make country music outside of Nashville. In the 1980s they would team up with Kristoffersen and Johnny Cash and perform and record as The Highwaymen.

Willie may seem ageless but this coming April 30 he will turn 80 years old. You would never suspect it from his playing, though; his unique and original style is an amalgam of many elements, including country, jazz, folk, blues and even traces of flamenco. He doesn’t have a guitar tech or roadie in his band—no one comes out between songs and switches guitars for him—it’s Trigger all the way. Before Willie takes the stage you notice Trigger standing in the center, and after waving to the audience Willie puts Trigger on; when the concert is over he takes him off—and not until; that’s when you know the show is done. It’s the most complete melding of man and instrument I’ve seen in concert—reminiscent of Leadbelly’s Stella Twelve-String guitar, and no one else.

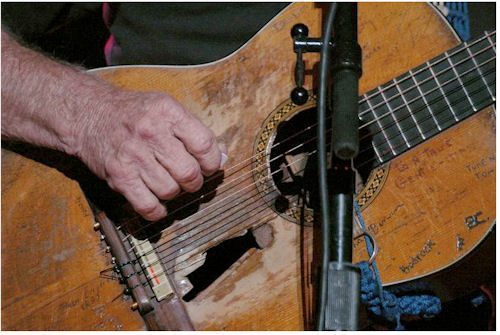

Like Cyrano’s nose Willie’s guitar is more famous than he is, and its reputation precedes him by a quarter foot; it’s a Martin classical N-20 he purchased for $750 after his original steel-string guitar newly refurbished with a three-cord pickup was smashed at a concert when a noisy drunk got up on stage and put his foot through it. Willie tried to have it fixed but the repair shop told him it was too far gone to repair. The owner mentioned that he just got a nice classical guitar in trade and Willie asked him to do a little open guitar surgery and transplant the pickup from his smashed instrument into the N-20. That is the guitar he has played ever since which bears the most famous name in country music.

Like Cyrano’s nose Willie’s guitar is more famous than he is, and its reputation precedes him by a quarter foot; it’s a Martin classical N-20 he purchased for $750 after his original steel-string guitar newly refurbished with a three-cord pickup was smashed at a concert when a noisy drunk got up on stage and put his foot through it. Willie tried to have it fixed but the repair shop told him it was too far gone to repair. The owner mentioned that he just got a nice classical guitar in trade and Willie asked him to do a little open guitar surgery and transplant the pickup from his smashed instrument into the N-20. That is the guitar he has played ever since which bears the most famous name in country music.

Since it is a classical nylon string guitar it was not made with a pick-guard—nor meant to be played with a pick. Over the years Willie’s hard playing has worn a Texas-size hole into the lower bout and the guitar could implode at any time—at which point Willie has already promised to retire from performing: “When Trigger goes, I go.” So, dear Reader, any concert could be his last, before he and Trigger ride off into the sunset. I noticed that he rides Trigger pretty hard, and kept my fingers crossed throughout the show.

Willie’s band is called “Family,” and he means it; they travel North America like a family on his bio-diesel tour bus— Honeysuckle Rose IV—demonstrating one of his vocal causes right down to his fuel tank—trying to get off of fossil fuels and work towards a sustainable planet. And BTW he uses his own brand of fuel, Bio-Willie. His sister Bobbie plays keyboards and they have been playing music together since they were children growing up in Abbott, Texas, where he wrote his first song at the age of seven. Willie gives his little sister two standout instrumentals during the show and she really stops the show—with a great version of Scott Joplin’s Maple Leaf Rag.

The band as a whole is great: Nelson’s touring and recording group, the Family, is full of longstanding members. Along with his sister Bobbie Nelson the lineup includes drummer Paul English (for whom Willie wrote a song, Me and Paul) harmonicist Mickey Raphael, bassist Bee Spears, and Billy English (Paul’s younger brother).

After the show was over the band really stepped up to the plate: for Willie’s show ain’t over till he’s signed all the autographs his audience wants, and while he’s doing it his band keeps the music coming—it’s really a show and a half—just an amazing and original transformation of the auditorium into something like his back porch. Throughout the concert he would punctuate it periodically by removing his signature headgear—both caps and bandanas and tossing them out into the audience to be caught by appreciative fans who will cherish them like a souvenir baseball hit by Stan “the Man” Musial.

Indeed, just walking into a Willie Nelson concert is tantamount to going to the circus: you are greeted by a “merchandising table” unlike any merchandising table you have seen—it stretches from the right theatre entrance to the left door—with caps, T-shirts, concert posters, “Trigger” keychains/USB ports, and a good selection of his more than sixty albums—all emblazoned with Willie Nelson & Family somewhere on them.

It is impossible to sum up what one of his autobriographies calls his Epic Life—for what other American artist has smoked marijuana on the roof of the White House?—which Willie did during the Jimmy Carter administration. What other American artist was prosecuted by the IRS for $32,000,000 in 1990 in back taxes? What other American artist has even made $32,000,000? And more to the point, what other American artist has conscientiously paid off his IRS debt himself, by releasing a double-album The IRS Tapes: Who’ll Buy My Memories and assigning all the royalties to the IRS? What other American artist saw his house burn down and manage to save only one artifact from the burning wreckage?—his guitar Trigger of course. What other American artist, fearing the IRS would seize Trigger like they had seized all his other assets, managed to hide the guitar out in his basement in Maui (where he resides) for three years—until he had paid off his debt—like an old country farmer determined to stand or fall on his own—with no help from the guvment, thank you. And finally, what other American artist—a lifelong Democrat—would sue the Texas Democratic Party for refusing to put Willie’s choice—2004 peace candidate Congressman Dennis Kucinich—on the ballot and in the debate?

To say that Willie is one of a kind dramatically understates the matter: Willie is really more like twenty of a kind—all by himself. He is a pure, unsweetened, 98 proof American original and a national treasure—who was awarded the Kennedy Center Honors for the Performing Arts in 1998.

Beyond his role as a performing and recording artist Willie has been a tireless voice on behalf of the American farmer; since family farms were being closed down in the 1980s from mortgage debt and loans were being called in by banks that had given up on them—and this in the nation’s bread basket midwest that had largely been subsumed by industrial-sized factory farms. Willie Nelson stepped up to a challenge fellow troubadour Bob Dylan made during a “Live Aid” concert in 1985, saying he “hoped some of the money would go to help farmers.” Along with Neil Young and John Mellancamp, Willie started FarmAid that year to make direct bequests to those who faced foreclosure. They raised $9,000,000 the first year and have been a part of the solution ever since.

It was out of this devotion that my friend the late “Banjo Fred” Starner and I were able to meet Willie in the summer of 2006, when he came to South Central Farm in LA, a three acre plot that was being used by three hundred families who were growing their own food in the industrial wasteland along the Long Beach Blvd corridor downtown. They were about to be evicted by the landlord, who after fifteen years wanted to pave paradise & put up a parking lot. Banjo Fred and I were there every day, singing Joni Mitchell’s Big Yellow Taxi and making up new songs for their vigils. Activist actress Daryl Hannah told Willie about their struggle and he gave us an inspiring day with his full support.

Even though nothing the protesters could do managed to save the farm from the legal system, it was a dramatic display that Willie Nelson’s sense of outrage, hope and courage extends far beyond his public persona as a country superstar. His last words to the local Latino and Black family farmers whose livelihood was in jeopardy—and who were engaging in Gandhian acts of civil disobedience to keep their precious garden of homegrown produce from being leveled—were, “Where I come from we’ll stay here until we get you out of jail, or we’ll get in there with you.” Inspiring words, but he already had his roundtrip plane ticket home.

And yet, seven years later, I am nothing but grateful to Willie for giving us that memorable day, and linking up an urban farm struggle with the much better known Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Post image of the American farmer. And I treasure having his autograph on all of my Willie Nelson albums and songbook. He showed me—outside of the limelight in which he usually travels—that Willie Nelson’s America is a full-color portrait, as Pete Seeger so eloquently described it, “of rainbow design.”

All of these memories were drifting through my mind during his concert. I saw first hand how Willie’s relationship with his audience is also unique; for a few songs they become the chorus; with Pete Seeger the audience literally “sings along with Pete” while he keeps on singing; but not with Willie: when he starts a chorus with, “Mamas,” the audience finishes it with “Don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys,” while Willie lays off and enjoys listening to them—us—become a part of the show. And let me tell you: everybody sings as if they had been rehearsing for a week. It was beautiful to be a part of.

I won’t say he saved the best for last, but his longstanding reputation for being a champion of legalizing marijuana, (and co-chair of NORML—National Organization for Reform of Marijuana Laws) after a generous 27 songs finally brought Trigger into the barn. When he asked the audience if they wanted “one more” we stood up again, including my fellow performer and medical marijuana advocate Jill Fenimore, for the third time, and he regaled us with a recent song that captures his outlaw spirit as well as any other—from the album Heroes—and is now also the title of his most recent memoir: Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die—Musings From the Road (with an Introduction by Kinky Friedman).

Quoting John Wayne’s farewell line from True Grit: Just don’t make it too soon, Willie. And thanks for the memories.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com

Willie Nelson and Family will be at The Hollywood Bowl Friday August 9 and Saturday August 10, 2013. Tickets have not yet gone on sale.

Ross Altman will host Rebels With a Cause, a tribute to Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson, and Phil Ochs on Tuesday, April 9, 2013 at The Talking Stick Coffeehouse at 1411 Lincoln Blvd in Venice, (310) 450-6052, 7:00 to 10:00pm—free and open to the public.

On Saturday, April 27 Ross will perform in San Diego at Adams Ave Unplugged; for info see www.adamsaveunplugged.org;

On Sunday, May 19 Ross performs at the Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest and Folk Festival; for info on tickets, contest registration and volunteer opportunities see www.topangabanjofiddle.org;

On Sunday, June 15 Ross returns to Claremont for the 30th Claremont Folk Festival; for info on tickets, a complete list of performers and volunteer opportunities go to www.claremontfolkfestival.org