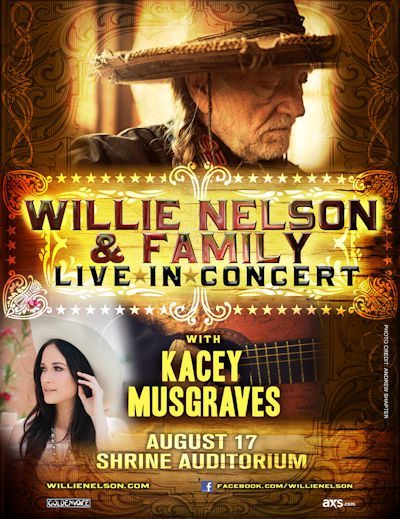

WILLIE NELSON IN CONCERT

WILLIE NELSON IN CONCERT

Shrine Auditorium Los Angeles – Thursday, August 17, 2017~9:30pm

The Voice of America

Climbing high up the half dozen long staircases to the second Mezzanine with my $43 ticket in hand—followed by another long staircase to the very top of the Shrine Auditorium—I was unwittingly high with no effort from myself, just from the second-hand marijuana smoke impossible to avoid. But I was in the building in time for Willie’s entire concert—from Whiskey River to his show-stopping closer: Roll Me Up and Smoke Me when I Die. His closer used to be On the Road Again, but he let that one out of the Great American Songbag (except for Hank Williams and Hoagie Carmichael, most of which he wrote) only 20 minutes into the show.

Climbing high up the half dozen long staircases to the second Mezzanine with my $43 ticket in hand—followed by another long staircase to the very top of the Shrine Auditorium—I was unwittingly high with no effort from myself, just from the second-hand marijuana smoke impossible to avoid. But I was in the building in time for Willie’s entire concert—from Whiskey River to his show-stopping closer: Roll Me Up and Smoke Me when I Die. His closer used to be On the Road Again, but he let that one out of the Great American Songbag (except for Hank Williams and Hoagie Carmichael, most of which he wrote) only 20 minutes into the show.

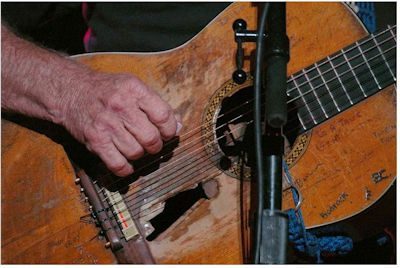

Willie turned 84-years old last April 29—and had to cut short his recent concert in Salt Lake City due to shortness of breath. He was hospitalized and sent alarm bells ringing from here to Austin, but he attributed it to the high altitude and said he felt fine the next day and looked forward to returning to sea level. Yippee Kay Yi Yay, I thought—we’re waiting for you in LA. It’s a good thing Willie was at sea level on stage—where I was sitting seemed like a mile up. Trigger—his antique Martin N-20—“This is my horse—that’s why I call him Trigger”—got him to the Shrine on time. Trigger was sitting center stage before Willie even entered, picked him up and put on his guitar strap. That’s a star.

The late great Pete Seeger had to work to get the audience to sing along; all Willie had to do was shout “Mamas!” and 6,000 plus devoted fans finished the chorus for him: “…don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys…” in tribute to fellow outlaw Waylon Jennings. It happened in song after song: Willie would say “Well hello there” and the whole audience would finish the sentence for him, “It’s been a long, long time” (Ain’t it Funny, How Time Slips Away”).

Way back in 1961 his friend and the greatest female country singer of all time—Patsy Cline—recorded his song Crazy. Two years later she got on an ill-fated small plane homeward bound from a show in terrible weather and went down to her death. Willie now remembers her with that classic—which presidential candidate Ross Perot appropriated for his campaign theme song in 1992 when the press began calling him by the title. It doesn’t seem like anyone actually wrote these songs—they are so much a part of our DNA—well beyond “hit songs.” But Willie Nelson wrote them—before he had long hair, a cowboy hat and a reputation for anything more than a successful Nashville songwriter—who wrote songs for other artists to perform. Then he moved to Texas and declared his independence from country music’s Nashville establishment. He became an “outlaw.” And with apologies to Paul Simon, he’s still “Crazy” after all these years.

Beer For My Horses, Good-Hearted Woman In Love with a Good-Timing Man, another duet with Waylon, Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground, On the Road Again, Georgia On My Mind, Always On My Mind, The Night Life, a song for Merle Haggard followed by a tribute to Hank Williams (with Jambalaya and Hey Good Lookin’) and an instrumental blues that gave his famed harmonica player Mickey Raphael a chance to shine; it was like looking at a jukebox onstage from the last row. Except that Willie built the jukebox. For these are not just Willie’s “greatest hits,” they are America’s greatest hits. The sound was gorgeous all the way to the back. It’s hard to believe that Willie’s guitar is not only not electric, it’s not even a steel-string acoustic.

Beer For My Horses, Good-Hearted Woman In Love with a Good-Timing Man, another duet with Waylon, Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground, On the Road Again, Georgia On My Mind, Always On My Mind, The Night Life, a song for Merle Haggard followed by a tribute to Hank Williams (with Jambalaya and Hey Good Lookin’) and an instrumental blues that gave his famed harmonica player Mickey Raphael a chance to shine; it was like looking at a jukebox onstage from the last row. Except that Willie built the jukebox. For these are not just Willie’s “greatest hits,” they are America’s greatest hits. The sound was gorgeous all the way to the back. It’s hard to believe that Willie’s guitar is not only not electric, it’s not even a steel-string acoustic.

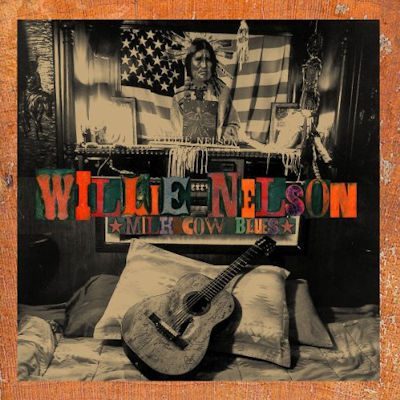

Trigger is a plugged-in amplified nylon string classical guitar—with the power of a Fender Stratocaster—it fills the whole auditorium. Willie is one of the greatest guitarists America has—every note is perfect from the first fret to the amazing 19th fret at the top. His next-to-last album is Milk Cow Blues—which he recorded before B.B. King passed away—so King’s great blues guitar Lucille pairs off in duets with Willie’s Trigger—bending strings near to the breaking point for every aching 7th note they can find. It’s a modern blues classic. He sang another blues, “Shoeshine Man” as an encore.

Trigger is a plugged-in amplified nylon string classical guitar—with the power of a Fender Stratocaster—it fills the whole auditorium. Willie is one of the greatest guitarists America has—every note is perfect from the first fret to the amazing 19th fret at the top. His next-to-last album is Milk Cow Blues—which he recorded before B.B. King passed away—so King’s great blues guitar Lucille pairs off in duets with Willie’s Trigger—bending strings near to the breaking point for every aching 7th note they can find. It’s a modern blues classic. He sang another blues, “Shoeshine Man” as an encore.

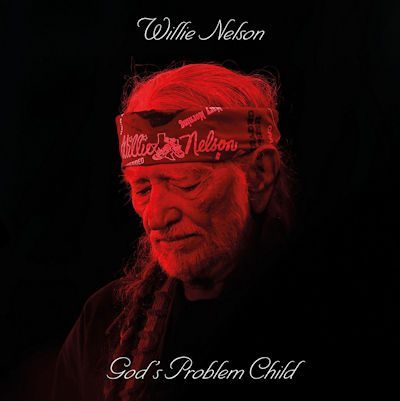

Willie’s most recent album is God’s Problem Child—which has his twisted version of John Donne’s Death Be Not Proud on it—Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die. Willie is unabashedly willing to sing about death right in his face. Before he reaches that closer he embraces classic country hymns like the Carter Family’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken and the traditional hymn I’ll Fly Away. Then he goes from songs about dying to death itself. That’s his answer to Mark Twain’s “Rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” Nelson actually saw rumors of his death in print, and decided they needed to be answered. Like a true artist he answered them with a song, Still Not Dead!

Willie’s most recent album is God’s Problem Child—which has his twisted version of John Donne’s Death Be Not Proud on it—Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die. Willie is unabashedly willing to sing about death right in his face. Before he reaches that closer he embraces classic country hymns like the Carter Family’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken and the traditional hymn I’ll Fly Away. Then he goes from songs about dying to death itself. That’s his answer to Mark Twain’s “Rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” Nelson actually saw rumors of his death in print, and decided they needed to be answered. Like a true artist he answered them with a song, Still Not Dead!

If it were a movie you could call it Love and Death and the Whole Damn Thing. Having taken his audience on a journey from love to death, he returns to Hank Williams classic hymn, I Saw the Light. At this point his family (his concerts are billed as “Willie Nelson and Family”) joins him on stage for the closing hymns—like an old-fashioned Grand Ol’ Opry show—with family gospel singing even after earlier songs about drinking and cheating belie the religious soul of country music. It’s a lesson in being able to walk and chew gum at the same time—or what John Keats called the poet’s ability to hold two opposing thoughts simultaneously. You might also call it Willie’s answer to Eugene O’Neill’s greatest play—“Long Night’s Journey Into Day.” The point is that a Willie Nelson concert is a journey—he takes you somewhere you didn’t expect to go—with some of the most beautiful music in the world to guide your way.

Willie is like Dante entering the dark wood—“Abandon hope all ye who enter here”—and being there with you every step of the way—from the Purgatory of love’s darkest and saddest moments to the Inferno of having to recover from substance abuse—whether drugs or alcohol—and repay the IRS for years of back taxes—(which Willie nobly did) and finally the Paradiso in 1998 upon turning 65 and being honored by the Kennedy Center for a lifetime of achievement as a great performing artist. Willie has done it all—we are so lucky to still have this great American with us—who is now experimenting with grain-powered bio-diesel alternatives to gasoline—with which he now powers his own tour bus across the country. Willie stands only 5’6” tall, but he towers over the industry he now represents. His recent album is therefore simply called Country Music.

For the past thirty-two years Willie has devoted himself to helping save the American family farmer with annual Farm Aid Concerts in Texas—which he honors with his one stage decoration—a backdrop of the Lone Star State flag behind him hanging from the rafters. It evokes Willie himself—Hank is gone, Johnny is gone, George is gone, and now Merle too is gone. But Willie—the Lone Star—is still very much with us—with Trigger. What a privilege to see him in concert—after having seen Van Morrison and Bob Dylan at the same honest venue; the perfect three-part Divine Comedy.

For the past thirty-two years Willie has devoted himself to helping save the American family farmer with annual Farm Aid Concerts in Texas—which he honors with his one stage decoration—a backdrop of the Lone Star State flag behind him hanging from the rafters. It evokes Willie himself—Hank is gone, Johnny is gone, George is gone, and now Merle too is gone. But Willie—the Lone Star—is still very much with us—with Trigger. What a privilege to see him in concert—after having seen Van Morrison and Bob Dylan at the same honest venue; the perfect three-part Divine Comedy.

And speaking of Willie Nelson’s response to hard times with Farm Aid benefit concerts, you may have an image in your mind of what a “family farmer” looks like; I did—he is probably Midwestern and undoubtedly white. But Willie also showed up to offer his full support for the Latino and black urban family farmers of South Central Farm in 2006, when my friend “Banjo” Fred Starner and I were singing there and committed ourselves to trying to save it from the wealthy landowner and real estate developer who wanted to sell it for development as an industrial parking lot. Actress Darryl Hannah was one of the full-time organizers of the effort to enlist local activists into occupying and resisting the landowner from evicting three hundred families who lived there and supported their children with food they all grew on the land. She called Willie Nelson and he flew in with his wife to join the struggle. It was a great day in the morning when Willie came to South Central Farm to lend his name and full-throated support for this quixotic but doomed endeavor. When it reached the point of actually committing civil disobedience to prevent tractors from throwing families out of the enclosed farm Willie addressed us all with these words of inspiration and comfort: “I just want you to know that you are not alone. Where I come from if you have to go to jail we’ll either get you out—or we’ll get in there with you.” That’s Willie Nelson. And before he had to get on the road again he graciously signed all of my Willie Nelson records and songbook—a mensch!

Likewise, at the Shrine Auditorium Willie threw his cowboy hat out into the front row for some lucky fan, and walked down to the edge of the stage and signed everything he could reach. The standing ovation started the moment he strolled onto the stage, and didn’t let up till the lights turned on at the end. And when he left the stage Trigger still stood proudly in his designated spot at the back. His own guitar roadie finally carried him off.

Willie is still looking forward, but he is not afraid to look back either—and honor in song the great country singers who came before him and with whom he shared the stage, like Hank Williams, Waylon Jennings and Merle Haggard. He keeps all of their names alive and presents sumptuous versions of their songs—and the first family of folk and country music, the Carter Family—along with his. He resolutely understands his role as country music’s elder statesman and most authentic voice. Willie truly is the Voice of America.

Sunday September 3, 10:15am Ross Altman returns for his 36th annual “Labor Day Sunday” appearance at the Church in Ocean Park, 235 Hill St, Santa Monica, CA 90404 310-399-1631. Ross will perform labor songs, stories and topical songs~

Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature from SUNY-Binghamton and belongs to Local 47 (AFM); Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com