TOM PAXTON SAYS FAREWELL ON 9/11

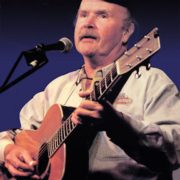

Tom Paxton Says Farewell on 9/11

Thanks for the Memories: At McCabe’s Guitar Shop (September 11, 2015)

Dylan, Paxton and Ochs

Started out singing for Cokes

Bob super-starred; Phil died hard

But Tom still sings for the folks.

~Ross Altman

The last thing on Tom Paxton’s mind last Friday night at McCabe’s was that this may be the last time he would be there. He still had a show to do, and a great show it was.

To say there was not a dry eye in the house might be overstating it, but not by much. In what has been announced as his farewell tour Tom Paxton gave a generous two-hour plus concert to a sold-out, adoring McCabe’s audience that gave him an enthusiastic standing ovation that left America’s greatest modern folk song writer visibly moved; his eyes at least were certainly not dry as he strolled up McCabe’s fabled onstage staircase into the upstairs green room for perhaps the last time.

He left us with two gold standards from the Great American Songbook, The Last Thing On My Mind and Rambling Boy and the title songs of his two most recent albums, Comedians and Angels and Redemption Road for encores, after the most moving song of the night—on the 14th anniversary of what Paxton described as “a black day in American history,” September 11, 2001—“a song,” he said, “for the heroes,” The Bravest his encomium to the firefighters he so memorably described as “coming up the stairs, while we were coming down”—one of the great lines in modern American song. Paxton has always had the gift of summing up the most critical situations in our national life with the most memorable lines:

Lyndon Johnson told the nation

Have no fear of escalation

I am trying everyone to please

And though it isn’t really war

We’re sending 50,000 more

To help save Vietnam from the Vietnamese.

Having just received an email from one of my lunatic fringe leftist friends promoting a number of pseudo-documentary films purporting to show that “9/11 was an inside job,” how refreshing it was to be restored to sanity by a folk singer who has been singing truth to power for more than 50 years. It was refreshing in the sense that Paxton has always been a man of the left, yet never tempted by the overstatements of its most radical fringe. Tonight he unveiled a new song from Redemption Road coming down squarely on the side of the most despised among us:

If the poor don’t matter

Then neither do I

echoing Eugene Debs’ famous line that wherever there is a man in prison, I am not free. Paxton is at his best when he speaks for those who have no one else to speak for them, as in his great song On the Road from Srebrenica—in which the name of the most notorious town to be victimized by ethnic cleansing closes the title of the song.

And before the word AIDS had ever slipped from the mouth of President Reagan, Paxton had already penned the most moving song of that terrible epidemic: Billy Got Some Bad News Today. America’s folk singers were far ahead of our political leaders in coming to terms with the scourge of HIV and AIDS—and Paxton inspired them with his example of how a song could embody the truth and translate it into human terms with a human story.

When women were fighting for an equal day’s pay for an equal day’s work Paxton wrote another great anthem for equal rights: Mary Got a New Job:

Mary got a new job working on the line

Helped to make the automobile

They learned the job together

Things were going fine

She liked the way it made her feel

But when they got their paycheck they dropped the envelope

Money was all over the floor

Mary saw the money

Saw to her surprise

Johnny had a whole lot more.

And she said, “Who’s been matching you sweat for sweat

Who’s been working on the line

Who’s been earning what she ain’t got yet

All I want is what’s mine

I got eyes and hands and a back like yours

I use them hard the whole day

I stand here working just as hard as you do

And I want my equal pay.”

And then the kicker at the end:

“And I want my ERA!”

On every front in the ongoing struggle for social justice Tom Paxton picked up where Phil Ochs left the battlefield from suicide in 1976, and Bob Dylan stopped writing “finger-pointing songs” ten years earlier for more personal poetry. Fortunately for the people Paxton never got tired of writing finger-pointing songs, and never succumbed to depression and despair to stop writing altogether. We have been blessed to have his singular intelligence and passion and sure sense of musical morality all through the Decade of Greed and subsequent slow slide into a deepening rightwing hold on the imagination. When Reagan insisted by neglect that AIDS didn’t exist, Paxton became a voice for those who were dying with opportunistic bedsores all over their bodies; when Bush insisted that equality in the workplace was not a priority Paxton became a voice for women who were only trying to advance from being paid 69 cents on the dollar for men.

And when the environment was being allowed to degenerate into polluted rivers that even fish could not swim in—let alone children—and strip-mined mountains that were decimated for coal Paxton raised the level of environmental songs to a high art with Who’s Garden Was This?, written in 1970 for the celebration of the very first Earth Day. It was one of the highlights of his farewell concert this evening.

But Paxton’s genius as a songwriter is many-faceted, and one of the most illuminating aspects is his brilliant satires that bring his audiences to delighted laughter as well as sympathetic tears. His trenchant verbal cartoon of the modern America phenomenon of Yuppies gave rise to his take-off on Ghost-Riders in the Sky with Yuppies In the Sky, and One Million Lawyers became the definitive comic masterpiece on the takeover of the marketplace by the surplus of lawyers:

In ten years we’re going to have one million lawyers

one million lawyers

one million lawyers

In ten years we’re going to have one million lawyers

How much can a poor nation stand?

And The Ballad of Gary Hart premiered a new age in presidential politics, when the Gotcha scandal became the constant preoccupation of press coverage; Paxton never ducked the tough ones, but when he saw low-hanging fruit he plucked it. And one of my favorite McCabe’s moments with Paxton was years ago when for his final encore he nailed the universal frustration with Rubric’s Cube: It’s Only a Game. Leave ‘em laughing? Tom did, again and again.

In 1980, with his transformative masterpiece The Paxton Report Tom Paxton introduced the subversive folk response to the bailout of the auto industry I Am Changing my Name to “Chrysler”:

I Am Changing my Name to “Chrysler”

I’m going down to Washington DC

I’ll tell some power broker

What you did for Iacocca

Would be perfectly acceptable to me

I am changing my name to Chrysler

I am heading for that great receiving line

And when they hand a million grand out

I’ll be standing with my handout

Yes sir, I’ll get mine!

Paxton has always stood for the common man and woman against the big machine, against corporate indifference and greed, and for the most vulnerable among us against those who resent any part of the social safety net or the reforms of the New Deal. He has been the voice for ignored and abandoned leaders like FDR and a torch bearer for the previous generation’s Woody Guthrie. He was able to walk and chew gum at the same time—distinguishing LBJ’s War on Poverty from his War on Vietnam, supporting the one while protesting the other.

And he has endured—since he signed his first recording contract with Jac Holzman of Elektra Records in 1964—the same label that recorded Phil Ochs, Theodore Bikel and Josh White. Jac Holzman was in the audience tonight, and kind enough to give me his autograph and talk to me during intermission. He suggested I read his recent memoir Follow the Music, with some wonderful stories about the singers and musicians (like Paxton) who made his label’s amazing contribution to American music possible. So I am passing it onto you. It was Holzman who took a new American actor no one had heard of outside the Broadway show he came here to open—a little thing called The Sound of Music—and turned him into the best-known Jewish folk singer of the folk revival—Theo Bikel. It was Jac Holzman who turned a South African singer who nobody knew but Harry Belafonte—Miss Miriam Makeba—and turned her into an international superstar.

And it was Jac Holzman who took a couple of pass the hat folk singers at the Gaslight and Gerde’s Folk City—Phil Ochs and Tom Paxton—and gave them a national platform worthy of their extraordinary gifts. Paxton introduced him from the stage and described him as his hero. He has certainly been mine too, for more than half a century. I was thrilled to be able to finally tell him so.

As in his previous McCabe’s concerts, Tom was accompanied by the two-man band of Fred Sokolow on slide guitar and banjo and his son Zac on mandolin and fiddle. They were just wonderful throughout—adding refined musical textures befitting a full band. They have been playing together for many years now and it shows—with just a modicum of communication on stage they always knew how to create a sonic landscape around Paxton’s word pictures that extended to stories about Agamemnon, Impressionist painters like Cezanne, and his indelible portrait of the late great folk music giant Dave Van Ronk.

But the most heart-rending and endearing moment of the night for this reviewer was Paxton’s beautiful tribute—in both spoken word and song—to his late wife Midge, who passed away just two years ago. He sang one of his early classic love songs, which he wrote for her as an engagement present when they got married, just six months after meeting at the Gaslight in January of 1963—My Lady’s a Wild Flying Dove:

My lady’s a wild-flying dove

My lady is wine

She tells me each evening

She’s mine, mine, mine.

She likes pretty pictures

She loves singing birds

She’ll watch them for hours

But I see only her.

Midge was just 18 when they met, and when they married according to Paxton after six months word on the street was that was how long it would last. But she—like so many of Paxton’s amazing songs—was a keeper. They were married fifty years and ten months before she passed away—and Paxton honors her with some of the most moving love songs of the past half century—songs like You’re So Beautiful, Home To Me (Is Anywhere You Are) and Wish I Had a Troubadour. She clearly was and remains his inspiration, as Tom Paxton has been ours. Thanks for the memories, Tom, for a great concert—and a life that has filled our world with some of the very best songs of our time. If this was indeed your farewell appearance you long ago put it in words and music:

Outward bound

Upon a ship that sails no ocean

Outward bound

It has no crew but me and you

Far behind

When just a minute ago the shore was filled with people

With people that we knew.

Chorus:

So farewell, adieu, so long, vayo con dios

May they find whatever they are looking for

Remember when the wine was better than ever again

We could not ask; we could not ask for more.

(Outward Bound, 1966)

You can find Tom Paxton’s music on his website.

With thanks to McCabe’s Concert Director Lincoln Meyerson and Assistant Brian Rogriquez who gave FolkWorks a much-needed Press Pass.

Monday evening September 28 at 7:00pm Ross Altman celebrates Ethel Rosenberg’s birthday in 1915 with the Ethel Rosenberg Centennial Concert; at The Los Angeles Workers Educational Center, 1251 South Saint Andrews Place 90019; $5.

Friday November 20 at 8:00pm Ross commemorates the Centennial of the execution of Labor’s greatest troubadour Joe Hill at Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center, 681 Venice Blvd, Venice, CA 90291 310-822-3006; $10.

Sunday evening December 20 at 7:00pm Ross Altman and a Small Circle of Friends celebrate Phil Ochs 75th birthday with a concert of his songs at Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center, 681 Venice Blvd, Venice, CA 90291 310-822-3006; $10.

Los Angeles folk singer Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature; for further information about any of these events Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com