THE RHYMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’

The Rhymes They Are A-Changin’

TITLE: The Lyrics: Since 1962

AUTHOR: Bob Dylan

EDITOR: Christopher Ricks, Lisa Nemrow, Julie Nemrow

PUBLISHER: Simon and Schuster

RELEASE DATE: October 28, 2014 (NYC)

The most complete collection of Bob Dylan’s lyrics we are likely to see in our lifetime has just been published, and the most notable thing about it is the juxtaposition of Dylan’s lyrical changes in many songs from their original recorded versions to the printed versions to the various live recorded versions, yielding in some cases three rather different texts. Each section is framed by a full-size replica of the original album cover, in full color front and back. The dimensions of the LP determined the size of the book.

The most complete collection of Bob Dylan’s lyrics we are likely to see in our lifetime has just been published, and the most notable thing about it is the juxtaposition of Dylan’s lyrical changes in many songs from their original recorded versions to the printed versions to the various live recorded versions, yielding in some cases three rather different texts. Each section is framed by a full-size replica of the original album cover, in full color front and back. The dimensions of the LP determined the size of the book.

As my rabbi pointed out after seeing Dylan’s third concert at the Dolby Theatre (I reviewed the first in these pages) Bob seemed to have altered the lyrics my rabbi knew in both Tangled Up in Blue and Simple Twist of Fate. What gives? He wondered; we are accustomed to hearing different tempos, arrangements, instrumentation, even melodies for many of Dylan’s classic songs in live performance; now must we also get used to different lyrics? At what point do we find it difficult to think we heard the same song?

So I decided to order the $200, 961 page, 13 pound book and find out for myself. It just arrived from Barnes & Noble in NYC and what can I say? Rabbi, Things Have Changed.

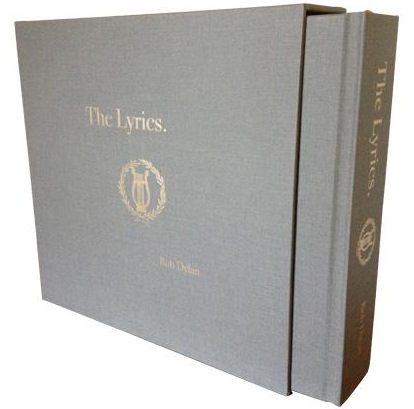

To begin with, this is Dylan’s coffee table book, but in a rather different sense from virtually every other coffee table book I have seen. This Loch Ness Monster of a book is big enough and sturdy enough to put the coffee table on, not the other way around. It comes wrapped in a box with more packing material than you would need for a small refrigerator—and like a Chinese puzzle it has a box within the main shipping box such that you have to open it twice before you actually reach the amazing book inside. The binding and cover and spine could not be more understated or more elegant—there are only four words on them: The Lyrics near the top and Bob Dylan near the bottom. Only when you open it to the title page do you see the complete title: The Lyrics: Since 1962.

The book is published by Simon and Schuster in New York City, and in one extraordinary act of publishing bravado they have utterly overwhelmed the noisy “Nobel Prize for Literature” with a silent act of worship of the collected works of the world’s greatest author of the past four hundred years on four continents since Shakespeare. This book is of biblical proportions—and I mean the Gutenberg Bible. It is a book that almost demands its own book stand or book case—like Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary. There are no promotional plugs anywhere on its vast surface; there are no tributes to Dylan—except for the brilliant introductory essay by its editor the former Oxford Professor of Poetry and himself now knighted Sir Christopher Ricks, distinguished author of a number of books on “high culture” poets like T.S. Eliot, John Milton, Alfred “Lord” Tennyson, John Keats, and, oh, did I mention, Bob Dylan (Dylan’s Vision of Sin—2003). It could not be more clear that Dylan is now fully considered their equal.

In addition to this being Dylan’s artistic masterpiece (of course the final song in the book is still When I Paint My Masterpiece), it may also be Christopher Ricks’ scholarly masterpiece as well. This is the book he has slowly built his academic reputation to be able to write.

I have a similar though not nearly as large a book in my personal library of great authors—a facsimile of Edgar Allan Poe’s first and most valuable book (on the rare book market), the nearly anonymous and privately printed Tamerlane and Other Poems. What makes that book—and this one by Dylan—so remarkable is that it (in an appendix) contains all of the known variants of the poems within—and many in Poe’s handwriting (not so here) as he revised them later on.

That is the distinguishing feature of Boston University Professor of Humanities Ricks’ edition: every one of the texts of Dylan’s famous and not-so-famous songs is not simply a reproduction from the three earlier versions of his lyrics—Writings and Drawings (1973), Lyrics: 1962-1985 and Lyrics: 1962-2001—rather each of the songs is transcribed directly from the records themselves, and thus contains a number of variants between the song as Dylan sang it in the studio, as printed in his published songbooks and then subsequent variations in live performance as represented by the series of official Bootleg Recordings that Columbia began to release in reaction to the unstoppable privately produced bootleg records that Dylan’s fans released. Notwithstanding Paul Valéry’s view of poetry (as attributed by W.H. Auden) that a poem is never finished, it is only abandoned, it is clear that Dylan continues to re-imagine even his best known songs with both minor and more significant lyrical changes—so that they never become set in stone.

Christopher Ricks has managed to preserve all those variant texts on the margins of the beautifully printed primary versions—and the editors have succeeded in finding subtle ways of including them without distracting the reader’s attention from the main text. The most significant feature of this graphic accomplishment is that there are a great many simply blank pages throughout, done in such a way that every song is completely contained within one double page layout in front of you at all times. You never have to turn the page to see the song continue to its end. It’s a masterstroke of design to go along with the rigorous editorial standards Ricks has maintained throughout. It is nothing less than astonishing to see three fully blank pages near the beginning, just so that when you turn the page you will see the entire song at one viewing on both pages displayed like an open dictionary.

My initial reaction to hearing early descriptions of this masterwork of the songwriter’s art and craft was frankly somewhat dubious—less than positive view of Dylan’s penchant for revising even his classic songs. “Call me when he’s revised Blowing In the Wind,” I remember thinking to myself—in full agreement with my Rabbi’s similar reservations. He wrote in response to an exchange of emails about my review of Dylan’s concert at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood:

“I was struck by, what I thought at the time, was his change of lyrics for both Tangled Up in Blue and Simple Twist of Fate. In thinking about it, it may be that what he recorded on the original album was different than the lyrics that were eventually published, and he was now singing the original lyrics. But while I vaguely recall that was the case for Tangled Up in Blue, I did not remember that happening for Simple Twist of Fate. So my question to you is: was Dylan also, now, changing his lyrics in addition to his long-time practice of changing the music?”

Best,

Rabbi

Dear Rabbi,

Yes, he does change lyrics and the new book The Lyrics: Since 1962 documents many live performance variations from the original recordings–which as you mention are sometimes different from the standard printed versions in previous songbooks and his web site. One such change just came up for this article; I remembered the quote I use from the recording of Property of Jesus (on the album Shot of Love) as:

‘Cause he doesn’t tell you jokes and fairytales

Say he fails to make you smile

but the printed version says:

‘Cause he doesn’t tell you jokes and fairytales

Say he’s got no style.

My editor went with the printed version.

Lisa Finnie’s wonderful Sunday morning show from KCSN (88.5 FM) The Dylan Hour is always playing rare live recordings and mentioning lyric variations from the official text.

It’s just the kind of thing that will keep English professors and editors gainfully employed in the future.

W.H. Auden once wrote, quoting Valéry I believe, “a poem is never finished; it’s only abandoned.”

For what it’s worth, I don’t happen to agree–and one takes issue on such matters with Auden (or Dylan) only at one’s peril. But I will start to pay attention to this in a more serious way when Bob changes Blowing In the Wind, which so far as I know has not yet happened. Though, and this I found very revealing at the time, there is a first draft of that song in his published Scrapbook which demonstrates that it did not come straight from the head of Zeus fully formed. He did revise it into its lasting form, and that is somehow comforting. It tends to confirm my occasional suspicion that it wasn’t G-d but an artist who wrote those songs.

Warmly,

Ross

To which my Rabbi replied:

Ross:

“…Much more profound is the issue of him changing lyrics. Why should we be less perturbed about his shifting tempos and, at times, changing the melodies for some of his songs than we are about him changing lyrics?

What’s the sense of changing horses in midstream? Well, for one, it is a refusal to let his music become, in any way, ossified. If some performers simply refuse to do old hits because they’ve already done them a thousand times in concert and they’re bored with it or because it’s “no longer them” or because they want to do something new, Dylan simply reworks them. In some ways, is this any different than jazz musicians? Each concert can be a new improvisation. We somehow expect that the lyrics will “stay put” and the melody will revolve around the words. But Dylan is far too mercurial for that. In some ways, there is no “there” there. What to hold on to? He changes the tempos, changes the melodies, changes the words. He puts on costumes and proclaims that he’s not the same performer. (Newport, Pat Boone’s Baptist Swimming Pool….) What’s real is the moment. Otherwise, he will not be pinned down: not musically, not personally, and not poetically.

And, yet, there’s something about his fluidity with the words that makes me uncomfortable. Perhaps as one who has spent a lifetime wrestling with the inherited word that we Jews have received. Now, it’s one thing to read a given text in all sorts of different ways. But, in the end, the text still remains. What does it mean when even the text can shift? Of course, this is where scholars can compare and contrast several manuscripts. But what is one to do when the author, himself, proclaims that the word is not static? It’s a bit disorienting. I understand the teaching that if one stands in a moving stream, the stream is different at every moment. I understand how the artist can proclaim the same. And yet, for us mortals….”

Rabbi

In reply, I had to admit:

Rabbi,

You’re preaching to the choir. I’m on your side on this; I plan to order the new “complete” lyrics book and review it for FolkWorks. When I’m able to consult some specific examples of these lyric changes I’ll perhaps have a more informed opinion. Anyway, if and when I do I will look forward to continuing this conversation.

Best,

Ross

And finally, from Rabbi:

“Yes. I’d be very interested in following up on this, especially the issue of why we feel it’s “ok” to change melodies but not lyrics. Something about the difference between the visual and the auditory? Sound moves but the written word is static? Yet Monet’s picture of the Rouen Cathedral or the Water Lillies – same picture taken at different times of day- also showed that what we thought was static also changes as a result of light. To be continued.”

Rabbi

Well, Rabbi, as you now know, I got the book and I still agree with you. There are some songs which Bob has not tampered with, not even a little—such as Boots of Spanish Leather—a good thing too I think, since it is now in the Norton Anthology of Poetry—and that would be like tampering with the tablets of the Decalogue.

However, thanks to this book I can now see the source of the difference between my editor’s carefulness and my own indelible recollections of listening to Property of Jesus; here are the lyrics Dylan actually sang on Shot of Love:

Because he’s not afraid of trying, say he’s got no style

’Cause he doesn’t tell you jokes or fairytales

Say he’s failed to make you smile.

Those are from the primary version of the song lyric as printed throughout this book—based on the original studio recording.

However, my editor went with the lyric as printed in Dylan’s third edition: Lyrics 1962—2001 (published in 2004):

Because he’s not afraid of trying, ’cause he don’t look at you and smile

’Cause he doesn’t tell you jokes or fairytales, say he’s got no style.

These are presented on the facing page as the alternate lyrics to the original. And evidently they are the ones on Dylan’s web site as well. What can I say? Rabbi, I prefer the original.

But don’t take my word for it. I still have a personal letter from Jeff Rosen—Bob Dylan’s manager and head of his publishing companies—written in reply to my request to put some of my lyrics to Bob’s melody for My Back Pages. Mr. Rosen politely but unambiguously and once and for all denied my request with apparently Dylan’s own words: “Bob Dylan does not allow anyone to put different lyrics to his music.”

I think those are words to live by that Bob Dylan should take to heart—and leave his classic songs alone. I would try to come up with some salient examples to support my argument, but unfortunately I put his book back in the box from whence it came for maximum protection, and at this time of night it is too heavy to lift.

In conclusion, dear Rabbi, if I know Dylan, he doesn’t give a damn what we think. That’s one of his more endearing traits that make him the genius he is. So, as he once wrote, I’ll bid farewell in the night, and be gone.

But to show you that I did look through the book somewhat carefully this morning, I will end with the one mistake I found in 961 pages: Playboys and Playgirls is described as “unreleased.” Prof Ricks is no folkie, or he would have known: Playboys and Playgirls was released—as a duet with Pete Seeger at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival by Vanguard Records.

And it is one of my favorite Dylan vocal performances—his nasal twang supported by Pete’s sturdy baritone harmony:

Ye red-baiters and race-haters

Ain’t a-gonna hang around here

Ain’t a-gonna hang around here

Ain’t a-gonna hang around here

Ye red-baiters and race-haters

Ain’t a-gonna hang around here

Not now, nor no other time.

I wouldn’t change a word. And neither did Bob.

Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com