THE LAST THING ON TOM PAXTON’S MIND

THE LAST THING ON TOM PAXTON’S MIND

McCabe’s – Saturday, April 1, 2017

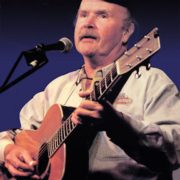

Now we know why they call them Dreadnoughts. Tom Paxton’s late great Santa Cruz Dreadnought (modeled after Martin’s famed D-28 and named like Martin’s for a stalwart British battleship) was smashed in an escalator fall Paxton sustained in Penn Station last year. But he was carrying it on his back and it cushioned his fall, thus likely saving him from a broken back or even saving his life. He brought it up during his concert, after I had already noted that he was playing his old Martin M-38, which I hadn’t seen him play since the late 1990s. I thought at the time that he had just gone back to it out of personal preference, until he brought up the accident later in the show. He mentioned that he was wearing fingerpicks, which he did not ordinarily use, due to injuries to his fingers in the backwards fall down the escalator. What might have been a small feature of this concert thus suddenly took on a larger meaning. Here he is, after all, now 79 years old, and still carrying his own guitar across the country since turning his back on retirement—which he had announced with an air of finality the last time I reviewed his September 11, 2015 show at McCabe’s. I made a bet with myself at the time that he would not stick to it, and would be back at McCabe’s as soon as he had some new songs he wanted to sing.

Now we know why they call them Dreadnoughts. Tom Paxton’s late great Santa Cruz Dreadnought (modeled after Martin’s famed D-28 and named like Martin’s for a stalwart British battleship) was smashed in an escalator fall Paxton sustained in Penn Station last year. But he was carrying it on his back and it cushioned his fall, thus likely saving him from a broken back or even saving his life. He brought it up during his concert, after I had already noted that he was playing his old Martin M-38, which I hadn’t seen him play since the late 1990s. I thought at the time that he had just gone back to it out of personal preference, until he brought up the accident later in the show. He mentioned that he was wearing fingerpicks, which he did not ordinarily use, due to injuries to his fingers in the backwards fall down the escalator. What might have been a small feature of this concert thus suddenly took on a larger meaning. Here he is, after all, now 79 years old, and still carrying his own guitar across the country since turning his back on retirement—which he had announced with an air of finality the last time I reviewed his September 11, 2015 show at McCabe’s. I made a bet with myself at the time that he would not stick to it, and would be back at McCabe’s as soon as he had some new songs he wanted to sing.

Well, dear Reader, that time is now, and he put on a triumphant return don’t listen to what I say—listen to what I do concert. His new album is called Boat in the Water, and the title song is a delightful ode to taking a trip out to sea just to say you had been there.

Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award-winner Tom Paxton came back to McCabe’s last night—the beginning of Act Two (of which F. Scott Fitzgerald said there were none) in a great American life. He returned to a theme he began at the end of his “retirement” concert last time, when he invited the now late Theodore Bikel on stage to share his encore, Ramblin’ Boy. This time Paxton invited special guest and old roommate Noel Paul Stookey to join him on stage for the same encore, Ramblin’ Boy, and it provided the perfect closing to a show in which Tom Paxton had already paid tribute to some of his legendary mentors—including Mississippi John Hurt, Dave Van Ronk and Pete Seeger. Stookey was utterly charming—knew how to lay low when the situation called for it, and provided warmhearted harmony and a sense of drama to the curtain call. During the song Paxton’s speakers started to growl with a feedback vengeance and no one on stage knew what to do except Stookey—who checked his guitar input and saw it had come unplugged. Without missing a beat, or even disturbing Tom’s attention to his lyrics, Paul plugged the cord back into the guitar and quelled the speaker’s annoyance so Tom could continue. The slightest raised comic eyebrow in Stookey’s expression let the audience know that we could now relax without further ado; it was so subtle you really had to be paying attention to even notice it—which I did, and was quite impressed with how smoothly he took care of an interruption which could easily have stopped the entire performance. That’s a professional, I thought, that’s a friend in need. Paul had no guitar on stage; he just kept his wits about him, and kept up his part of the harmony throughout. (Spoiler alert): What a perfect end to a great show!

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Tom put on a great show—backed by his new band, who did double service as the opening act—the Grammy winning singer/songwriter duo The Don Juans — lead guitarist Don Henry & keyboardist and harmonium player Jon Vezner—whom he joked he “picked up on the 405,” and opened with his lovely song based on a line from Isaiah: How Beautiful Upon the Mountain (Are the Steps of Those Who Walk in Peace). That’s when he added that he had “come out of retirement”—indicating that he assumed a lot of folks in this sold-out house would have been there the last time—and cheerfully amended, “Well, forget about that; I’m having too much fun!” which got an immediate round of applause. I find in my notes at that point “M-38.” It’s a beautiful late-in-the-game Martin 0000 design, which Arlo Guthrie and David Bromberg both use as well. (I have the M-36 version with a three-piece back—the late Kim Friedman’s guitar which I bought and wrote about after she passed away in 2015.)

Then he sailed into the title song of his brand new album—Boat In the Water—which he paused at the beginning to joke, “I don’t know what your rhyming dictionary says, but in mine “water” rhymes with “oughter” and that’s how we’re going to sing it:

Let’s put our boat in the water

And do what we oughter.

He got a great laugh with that observation—and everyone started singing along.

With that he performed a powerful indictment of the way the poor are now treated in this country, which evoked a classic line from socialist Eugene Debs:

While there is a working class I am of it

While there is poverty I can’t rise above it

And while there is a soul in prison

I am not free.

Paxton’s song develops from his similarly moving refrain:

If the poor don’t matter

Then neither do I.

After the extended eloquent middle rap passage describing all the examples of how poor people are disregarded in this society, he made a biting remark at the end by noting that he did not like the way some “religious types” would use religion to justify ignoring the suffering of the poor; concluded Paxton: “Why don’t they just admit they are ‘a-holes’?” (But he used the complete word).

At that point he told the rather shocking story of his accident on the escalator in Penn Station, which put the M-38 he was now playing again in perspective. It made me think that if Santa Cruz replaces his smashed guitar they could make it a true Tom Paxton signature model by adding in the front, where Woody scrawled “This Machine Kills Fascists,” “This Machine Saved My Life.”

April 22nd upcoming will be the 47th anniversary of the founding of Earth Day by Senator Gaylord Nelson, in 1970. That’s when songwriters responded and started writing songs for the Earth; Pete Seeger wrote My Rainbow Race that year. This evening Tom delivered his first Earth Day classic song from 1970 Whose Garden Was This without saying a word about the current climate change controversy, or the president’s recent announcement that we would no longer abide by the Paris Agreement of last year—just one of the many stunning announcements in denial of every scientific warning about global warming we have heard from this White House, and his new EPA appointee during the confirmation hearings. Paxton didn’t have to; his song spoke for him:

Whose garden was this

It must have been lovely

You say it had flowers

I’ve seen pictures of flowers

And I’d love to have smelled one

Whose forest was this

it must have been lovely

You say it had breezes

I’ve heard records of breezes

And I’d love to have felt one

Chorus:

Oh tell me again I need to know

Forests had trees

Meadows were green

Oceans were blue

And birds really flew

Can you swear it was true?

A great work of art like Paxton’s song is undeniable—just like the science it is based on. It is Paxton’s still illuminating answer to those idiots now in charge of America’s environmental policies, and willing to ignore worldwide opinion based on scientific evidence. That is why I had to leave the Folk Club to hear him again. I brought Jill Fenimore, who recorded Paxton’s masterpiece The Last Thing on My Mind in her own fingerstyle arrangement, with me.

But even there Tom Paxton’s gentle wit shone through: he wound up saying that he didn’t mind environmentalists telling him what to do “as long as they’re not telling me not to go to 7-11.”

Tom followed his secular hymn to the earth with one of his newer songs from his second-to-last album Redemption Road, And If It’s Not True, a personal artistic fairy tale taking him on a journey back to the Impressionists in France, in which every verse makes you believe (or want to believe) that it’s really happening, leading up to the chorus:

And if it’s not true

what harm can it do?

I know what I know

And I go where I go.

It’s a charming defense of the artistic imagination, just as the previous song was a powerful defense of the scientific imagination. There’s a place for both—and both are necessary—so long as you know which is which.

Having taken us to France (both the unstated Paris Climate Agreement and the richly imagined Impressionist painters he pays homage to) he was in no hurry to leave. Paxton closed out the first set with another of his classic songs, Bottle of Wine—to which he gave an unexpected denouement—singing the chorus in French, and telling us why. He said that, like a number of his songs, this had been mistakenly identified in print as “a French folk song.” He then added, “Well it’s not a French folk song…it’s my own damn French folk song!” And the audience sang it too! (Or maybe that was my imagination—I suspect he added one last chorus in English for us.)

C’est tres jolie!

During the second set Tom grew into his newfound role (since Pete’s passing) as elder statesman of the folk music community, paying tribute to his beginnings in the Greenwich Village folk scene of 1962, when he recorded his very first record (just newly released on CD) Live at the Gaslight. Already there were friends-to-be Dave Van Ronk (who arrived in 1959) and Bob Dylan (who arrived in “the coldest winter in seventeen years,”—from Talking New York—1961. With Tom they had a troika. Of course Maria Muldaur was born there, in 1943. One of the legends who linked the old world of folk from the 1920s and ‘30s—in the Mississippi Delta—to the revival of the 1960s and came to Greenwich Village in 1963 was Mississippi John Hurt—who Paxton celebrated in his song Did You Hear John Hurt?

Did you hear John Hurt

Play his Creole Belle

Spanish Fandango

That he loved so well

Did you see John Hurt

Did you shake his hand?

Did you hear him

Sing his Candy Man?

He plays it finger-style and the syncopated rhythm is just close enough to the master to evoke the flavor of John Hurt’s unmatched picking. Paxton said he soaked it up by osmosis when Hurt was booked for two weeks at the Gaslight, during the same time he was there—perfect timing. If you want to hear it performed by another modern master listen to Doc Watson play Paxton’s tribute to Hurt.

Paxton followed this with a perfect segue into his next song—his new (also from Redemption Road) and hugely entertaining tribute to the first real friend he made in the Village—Dave Van Ronk, “The Mayor of MacDougal Street.” At the end he mimics Van Ronk’s almost inimitable gravelly voice—by scat singing to the melody. It’s a brilliant and unmistakable recapturing of the original—just beautiful, and it proves that Paxton had genuine talent as an actor, which was what he started out to be. It was Van Ronk who inspired the lead character of the movie Inside Llewyn Davis—which spun its title and portrait of the early folk scene from Van Ronk’s first Folkways Record of 1961, Inside Dave Van Ronk. I reviewed the movie for FolkWorks when it came out in December of 2013: The Coen Brothers Rocky Road to Greenwich Village: Inside Lewyn Davis.” It recounts some of that early history I don’t have time to repeat here.

Finally, for those hoping to hear at least one new political song to rescue a thread of hope for democracy out of the blazing bundle of frenetic anti-immigrant, anti-health care, anti-freedom of the press, anti-respect for science, truth, and women, anti-civil rights and voting rights actions and the plethora of angry tweets towards the downtrodden and dispossessed emanating from the White House since January 20, 2017, Paxton saved the best for last—the first song he co-wrote with his band-mates the Don Juans, a brilliant satire on various kinds of “alternate facts” and alt-right fictions masquerading as truth promulgated by the president. It’s called, What’s So Bad About That? and it’s a keeper.

That’s about all the time I have to tell you about Tom Paxton’s comeback kid concert of 2017, except that he closed with Jill’s favorite—The Last Thing on My Mind. Jill especially loved their full three-part harmony a capella singing opening chorus and verse, which made a love song sound like a church hymn. We and McCabe’s full house gave Tom, and Don and Jon, a well-earned standing ovation—for a concert to remember.

How can you keep from singing, Tom? And retirement?—It’s the last thing on his mind.

Sunday, May 21, 2017 at 4:00pm on the Railroad Stage Ross Altman performs “The Greatest Show on Earth: The Circus in American Folk Music” to commemorate the final show of Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, which takes place the same day. See the Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest and Folk Festival website for information, volunteer opportunities, the deadline for and how to register as a contestant, and tickets. There is still time!

Saturday, May 27, 2017 at 2:00pm at Allendale Branch Library in Pasadena Ross Altman performs his one-man show “Ask Not: JFK 100,” a musical celebration of President John F. Kennedy’s Centennial (May 29, 1917-November 22, 1963); 1130 South Marengo Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91106; 626-744-7260 (Free).

Los Angeles folk singer Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature from SUNY-Binghamton and is a member of Local 47, now in its 120th year representing working musicians; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com