THE GERSHWINS’ PORGY AND BESS

Send In the Clowns:

The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess

At The Ahmanson Theatre: April 23rd, 2014

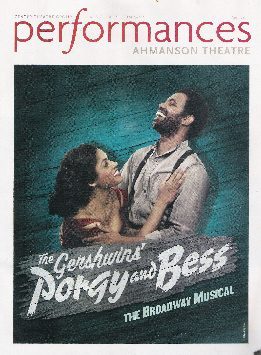

“Is that it?” were the first words out of Jill’s mouth as the last notes died away from The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess at the Ahmanson Theatre. In other words, “Is that how it ends?” In still other words, “where’s the Broadway Musical?” You know, the one that ends the way a love story is supposed to end—with Porgy and Bess in each other’s arms—or dying in each other’s arms, just the way they look on the Marquee picture that’s advertising the show. It’s beautiful, in living color, just the way you want to remember them. But there is something wrong with this picture: what they’re advertising is not what they deliver. Jill could almost have asked, “Where’s the beef?”

“Is that it?” were the first words out of Jill’s mouth as the last notes died away from The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess at the Ahmanson Theatre. In other words, “Is that how it ends?” In still other words, “where’s the Broadway Musical?” You know, the one that ends the way a love story is supposed to end—with Porgy and Bess in each other’s arms—or dying in each other’s arms, just the way they look on the Marquee picture that’s advertising the show. It’s beautiful, in living color, just the way you want to remember them. But there is something wrong with this picture: what they’re advertising is not what they deliver. Jill could almost have asked, “Where’s the beef?”

What they deliver is something more profound: a Shakespearian tragedy, a Greek tragedy, or Dreiser’s An American Tragedy—but not what Rodgers and Hammerstein, Lerner and Lowe, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter or George M. Cohan would call “a Broadway Musical.” That’s why George Gershwin called it “a folk opera.” In opera you expect to see dead bodies on the stage, as you do here—the defining moments of both Act I and Act II.

So it’s anything but love triumphant that you are left with, as the devastated and abandoned Porgy resolves to leave Catfish Row and follow Bess to New York. The problem is that Bess did not go to New York alone and ask Porgy to follow her; she went with her drug dealer Sporting Life—who managed to outlast both Porgy and Bess’s other lover—the violent and abusive stevedore Crown—who Porgy murders in Act 2, thinking that he had disposed of his only competition for the hand of Bess, the “liquor-swilling slut” he had the good heart to take in when Crown abandons her in Act 1 to go into hiding after he murders Clara’s husband Jake after losing to him in a crap game when no one else in the community would take Bess in.

Porgy had no idea of the depth of her addictions to both alcohol and cocaine—but Sporting Life did, and he just bided his time, like Iago waiting in the wings. Sporting Life lives by his wits (as displayed in his big number—It Ain’t Necessarily So—and as soon as the courageous and crippled beggar Porgy finally stands up to the bully and rapist Crown and kills him with the knife he hid in his leg brace, Sporting Life pounces and hides some “happy dust” in Bess’s pocket, knowing she can’t resist it and will soon be coming back to him for more.

And that’s why DuBose Heyward got it right the first time, when he named his novel Porgy—the classic tragic hero of his original story—who sacrifices all for the love of an alcoholic and cocaine addict—and is left with only the bitter aftertaste of her drug-fueled inability to resist either the violent love of Crown or the seductive substance abuse-dependency foisted on her by Sporting Life. George Gershwin added Bess to the title to distinguish it from the play adaptation DuBose and Dorothy Heward had mounted as a Theatre Guild success on Broadway, which ran for 367 performances, far surpassing the commercial failure of 124 that George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess logged in for 1935.

But don’t take my word for it: Before the American Repertory Theatre production of The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess even hit the boards at Harvard University August 17, 2011 Stephen Sondheim, the most successful composer on Broadway also had a problem with it; he too didn’t like the title, but for a different reason: He wrote a withering letter to the New York Times to ask if anyone was expecting to see the Rodgers and Hart Porgy and Bess. He didn’t like putting the brothers’ Gershwin in the title and leaving out the source of the story—DuBose Heyward’s novel Porgy. Sondheim also pointed out that Heyward did not just write the novel and libretto for the original opera; he wrote many of the best song lyrics as well, including the show’s unquestioned masterpiece, the lullaby Summertime—which is reprised four times during the musical—growing in stature with each performance. Ira Gershwin was by far the better-known lyricist, so it’s not surprising his name would become associated with these lyrics:

Summertime & the livin’ is easy

Fish are jumpin’ & the cotton is high

Your daddy is rich and your mama’s good lookin’

So hush little baby, don’t you cry.

The problem is Ira Gershwin—the other Gershwin in The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess—didn’t write those lyrics: Novelist and poet DuBose Heyward did—as a poem for his wife Dorothy’s adapted play that George Gershwin set to music when he started working on adapting Heyward’s novel Porgy as an opera in 1934. In 1926 Gershwin had said that he had hoped to fall asleep reading it and instead he “read himself wide awake.”

The problem is Ira Gershwin—the other Gershwin in The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess—didn’t write those lyrics: Novelist and poet DuBose Heyward did—as a poem for his wife Dorothy’s adapted play that George Gershwin set to music when he started working on adapting Heyward’s novel Porgy as an opera in 1934. In 1926 Gershwin had said that he had hoped to fall asleep reading it and instead he “read himself wide awake.”

His brother Ira Gershwin didn’t come on board until much later, when George Gershwin decided he wanted to expand the lyrical voice for the music he was writing—a fusion of jazz, American folk, Negro Spirituals, Tin Pan Alley and European opera traditions—something he later described as “a folk opera.”

Wrote Sondheim in his introduction to the section on DuBose Heyward in Invisible Giants: Fifty Americans Who Shaped the Nation But Missed the History Books: “DuBose Heyward has gone largely unrecognized as the author of the finest set of lyrics in the history of the American musical theater—namely those of Porgy and Bess…But most of the lyrics in Porgy—and all of the distinguished ones—are by Heyward…His work is sung, but he is unsung.”

Well, not all of the distinguished ones, Mr. Sondheim; Ira Gershwin wrote the lyrics to It Ain’t Necessarily So, Sportin’ Life’s skeptical masterpiece questioning the authority of the bible that raises the curtain on Act 2. Somehow over Mr. Sondheim’s objections the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess won the Tony for best revival in 2012 and “The Broadway Musical” is now touring the country, with Book Adapted by Pulitzer-Prize winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks and Musical Score Adapted by two-time OBIE Award winner Diedre L. Murray and directed by McCarthur Genius-Award winner Diane Paulus. That’s more prizes than George Gershwin won in a lifetime. It took two years to get to Los Angeles but it was worth the wait. Jill and I saw the opening night performance on Shakespeare’s 450th birthday, April 23, at the Music Center’s Ahmanson Theatre. And where better to celebrate the bard’s 450th birthday than in a theatre?

Like Othello the tragic hero is black, like Hamlet there’s a dead body on stage at the beginning of Act 1, and another by the middle of Act 2, and like Macbeth there is a treacherous woman along for the ride, so if you like Shakespeare you’ll feel right at home. I felt like singing Happy Birthday, except it would have lowered the musical level.

You see, this folk opera was written by America’s greatest composer—the composer of Rhapsody In Blue—and a tragic figure in his own right—who died of a brain tumor at 38 just two short years after his crowning stage achievement premiered on Broadway and closed after only 124 performances—leaving its composer crushed and believing his ambitious attempt to create an American opera worthy of its European forebears had failed. It was like Leadbelly dying in December of 1949, just six months before his theme song Goodnight Irene became the number 1 song in the country and was declared the song of the half century by Life Magazine.

In 1959, legendary film director Samuel Goldwyn got involved, though very reluctantly. His famous initial reaction to the offer to make a movie of the stage work was simple, eloquent, and devastating: “Blacks won’t see it because it was written by a Jew; Jews won’t see it because it was written about blacks; and no one will see it because it’s an opera.” But he came around and the movie starring Sydney Poitier (because Harry Belafonte refused to play the lame beggar Porgy on the grounds that it was a racist portrayal of southern blacks) and Dorothy Dandridge got made. This was just one of many controversies surrounding the gradual acceptance of Porgy and Bess as a classic.

Preeminent among those controversies was the initial fact that DuBose Heyward, the Southern white novelist’s book Porgy was based on a real Charleston, South Carolina local character named Samuel Smalls, aka Porgy.

The name was thus not a novelist’s invention, nor the disabled black beggar who—along with using a push board—rode a goat-cart in the dismally poorest black part of town referred to as “Cabbage Row,” for the little vegetable stands that sold cabbage heads up and down the streets. “Goat Cart Sam’s” goat was widely known to smell terrible, as was Porgy. And yet it did not keep him from finding a faithful wife who Porgy himself was responsible for moving onto James Island off the shore of Charleston. In the novel and subsequent play, opera and now Broadway Musical James Island became Kittiwah Island; Porgy became a sympathetic, dissolute beggar who swapped his push board and goat cart for a leg brace and most noticeably from the standpoint of poetic license, his devoted wife became the local “liquor-swilling slut” named Bess.

And Cabbage Row of course became Catfish Row—more famous now than Steinbeck’s Cannery Row and an emotional precursor to Dylan’s Desolation Row. But most dramatically of all in terms of the poetic impact of the story, Heyward’s novel’s ending was fundamentally altered so that when his cocaine-addicted wife Bess is finally lured to New York by her drug dealer Sportin’ Life, Porgy (unlike his real namesake who just said “c’est la vie”) is shown in the final scene about to leave Catfish Row and try desperately once more to win her back—after having lost her previously to her violent, abusive former lover Crown. Porgy is the one decent man in her life, caught between Crown and the flashy hustler Sportin’ Life, who is always able to count on Bess’s need to get high, her drug-dependence to keep her tied to him throughout—so much so that she is shown in utter degradation sniffing coke on the floor when Sportin’ Life’s “happy dust” slips out of her pocket. Like Cocaine Bill and Morphine Sue, Bess has cocaine all around her brain.

DuBose Heyward’s first published story was called “The Brute.” He was already working on the characters that would later wind up in Porgy—where “the brute” became the violent stevedore Crown. And Porgy—though based on Samuel Smalls—also had ties to his own life. You see Heyward contracted polio at 18, and was himself disabled. Maybe we all are, and don’t know it; as Dylan said in 4th Time Around,

And you, you took me in,

You loved me then

You never wasted time

And I, I never took much

I never asked for your crutch

Now don’t ask for mine.

“How does it feel?” asked Bob in another song. How does it feel to be sitting next to a woman who could have been Bess when Porgy says to her, “I know you been with Crown.” I recognize the symptoms of desperation Porgy feels, and incapacity to learn from his mistakes. How does it feel to lose the same woman twice? I can identify completely with both songs, Bess, You Is My Woman Now and the even more heart-rending I Loves You, Porgy—which she sings to her twice-abandoned disabled husband just before leaving him again for NYC with Sportin’ Life. I well know that—as Carson McCullers, another southern novelist schooled in the crooked highway of love wrote, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. I would have been right on that doomed, existential boat with Porgy at the end. How does it feel to say I Got Plenty of Nothing? I know that too, so who am I to judge poor Porgy? We’re brothers beneath the skin.

That’s the picture that should be in the window—Porgy with his back to us, hobbling on his cane, with his eyes lifted toward the horizon, still on the prize—his true love Bess.

This amazing production succeeds on every level—the music is sung with complete authority, the actors are great—Nathaniel Stampley and Alicia Hall Moran star as Porgy and Bess, with Alvin Crawford as Crown and Kingsley Leggs as Sportin’ Life.

How good was it? Good enough to break your heart. It broke mine.

Indeed, therein lies the power of this hypnotic story, in all its historical guises it transcends one small impoverished black community in Charleston in the 1920s and speaks to the permanent human condition of love and loss, hope and heartbreak.

Porgy and Bess will be playing until June 1 at The Ahmanson Theatre at the Music Center. Go see it. And tell Bess I said hello. Better yet, send in the clowns.

For tickets and information go to: Center Theatre Group. With thanks to Phyllis Moberly and Jason Martin of the Center Theatre Group for press passes.

On Sunday, May 18 at 4:30pm on the Railroad Stage of the Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest in Paramount Ranch, Ross Altman will present Sing Out for Pete!, a tribute to Pete Seeger; go to the Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest website for tickets, information and volunteer opportunities.

On Sunday, May 25 Ross Altman will be honored by the Chinese human rights organization the Visual Artists Guild for his song Tiananmen Square, which he will sing in Chinese. See his May/June column Tiananmen Square for details and reservations.

On Saturday, May 31st 2014 Ross will present a protest song workshop and concert at the Claremont Folk Music Festival at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden 10:00am-9:00pm.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com