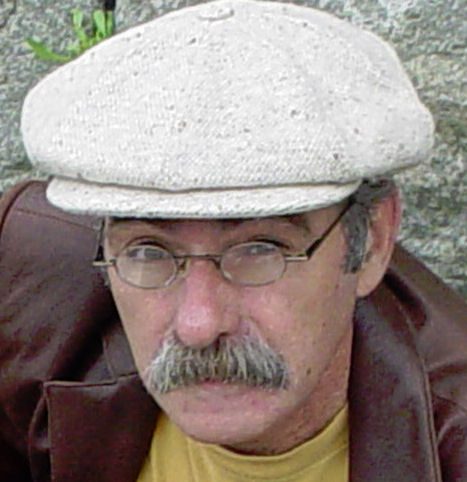

ROY BOOK BINDER RETURNS

ROY BOOK BINDER RETURNS

McCabe’s Guitar Shop – June 11, 2017 8:00 PM

Road Scholar

Blues and ragtime finger-style guitarist Roy Book Binder has come a long way since paying Harlem street singer and preacher Reverend Gary Davis $5 for guitar lessons. That was 49 years ago—when he started his quixotic career as a modern inheritor of the great American blues tradition going back to its founding father W.C. Handy’s St. Louis Blues in 1914. Book Binder has been on the road since 1968, when he recorded his first song for Blue Goose Records—Jimmy Rodgers’ He’s In the Jailhouse Now. You could see and feel his enthusiasm for the upcoming milestone in every song he sang and carefully crafted story he told to enlarge the context for his songs~ he mentioned several times that next year would be his fiftieth anniversary as a performing and recording artist, and he felt privileged to have been able to make a living doing what he loves to do. He thanked McCabe’s loyal audience for helping to make it possible, and our standing ovation expressed our own appreciation for his dedication.

Blues and ragtime finger-style guitarist Roy Book Binder has come a long way since paying Harlem street singer and preacher Reverend Gary Davis $5 for guitar lessons. That was 49 years ago—when he started his quixotic career as a modern inheritor of the great American blues tradition going back to its founding father W.C. Handy’s St. Louis Blues in 1914. Book Binder has been on the road since 1968, when he recorded his first song for Blue Goose Records—Jimmy Rodgers’ He’s In the Jailhouse Now. You could see and feel his enthusiasm for the upcoming milestone in every song he sang and carefully crafted story he told to enlarge the context for his songs~ he mentioned several times that next year would be his fiftieth anniversary as a performing and recording artist, and he felt privileged to have been able to make a living doing what he loves to do. He thanked McCabe’s loyal audience for helping to make it possible, and our standing ovation expressed our own appreciation for his dedication.

This was the highlight of McCabe’s 2017 season. Book Binder had started out at the Merlefest—named for Doc Watson’s late son in Asheville, North Carolina and slowly made his way out west. It was only later we found out that Roy now books for Merlefest, and makes a point of booking women fingerpickers for the festival. My favorite fingerstyle guitarist Jill Fenimore was sitting next to me, and we shared a knowing look at that bit of inside information.

His laconic style of storytelling and singing is well known; no razzle dazzle—except for his incomparable finger picking that carries on the syncopated rhythmic variations and subtle metrics of Rev. Davis, and others like Pink Anderson, Mississippi John Hurt, Big Bill Broonzy, King of the Delta Blues Robert Johnson, and Blind Blake and Lead Belly’s friend (“He was a blind man and I used to lead him around”) Blind Lemon Jefferson. A Roy Book Binder concert is a journey back into the mystic sources of America’s most singular music—which eventually gave rise to jazz—and extraordinary characters who crossed over into the white folk revival of the 1960’s, whereby revivalists like the Greenbrier Boys mandolin player Ralph Rinzler became obsessed with tracking down the Avalon, Mississippi songster John Hurt and Texas songster Mance Lipscomb and bringing them to the Newport Folk Festival in 1963 and 1964.

Often that is where folk revivalists like Roy Book Binder first got to hear them—if not at Gerdes Folk City in Greenwich Village. Their music might have been lost forever if not for ancient record collectors who would search out classic 78s in dusty record bins and see that they were preserved and eventually reissued on then modern 33 1/3 LPs. That’s how John Hammond’s Columbia recording of Robert Johnson rescued his 1936 /1937 sessions of 29 tracks for the American Record Corporation from the dustbin of history.

If not for artists like Book Binder they might remain mere library acquisitions that are never heard live and preserved as a living document of America’s best music. That is why I continue to follow and pay homage to Roy—and his fellow blues travelers John Hammond, and David Bromberg and Stefan Grossman, Keb Mo, Spider John Koerner—and Bonnie Raitt. They are a merry band of brothers and sister who share a collective unconscious steeped in the blues and a certain style of guitar playing that came out of rural America in what Langston Hughes defined in a 1926 poem as “I, Too, Sing America/ I am your darker brother.” Hughes, like Rev Davis, emerged from the Harlem Renaissance, but he also spoke for black people in the South—like the great aforementioned blues singers and guitarists from Mississippi, North Carolina, and Texas.

These days Roy Book Binder is in tall cotton; he lives in Florida and his tour bus would be thrown out of the Delta and other places associated with the roots music he performs. It’s a top-of-the-line Mercedes Benz ERA motor home with license plates that pay tribute to the effort to “Save the Florida Sea Turtle.” When Janis Joplin prayed in song “Oh Lord won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz?” the Lord must have been listening and gave an extra one to blues guitarist Roy Book Binder. It must feel a little ironic to sing a hard times song like Match Box Fits My Clothes or Broke Down Engine with the symbol of luxury waiting at the curbside to take you to the next gig. It’s not exactly the Grapes of Wrath with its broke-down jalopies lined up with the fictional Joads and real-life Woody Guthrie to get across the California line.

But I’m not complaining; it’s a good thing that an artist who has devoted his life to preserving the best American music that represents us to the rest of the world does not have to spend his retirement years in a degraded condition of poverty—even if that is what gave rise to some of his best songs. As Texas blues master Lightning Hopkins once said when someone confessed to him that he didn’t “know what the blues were—because he’d never had them.” “Just wait,” said Lightning, “You don’t have to look for them; they’ll find you. Nobody gets through life without ‘em.” Lightning spoke volumes.

He began by paying tribute to “his late wife—‘may she rest in peace’—then drolly added “with her new husband in Biloxi, Mississippi.” As he launched into Pink Anderson’s song Travelin’ Man, about a man who couldn’t be caught, he created the delightful soundscape of a band onstage with the aside, “Pick it, Roy!” leading into his guitar break.

He then described his “near brush with stardom” which was undermined by a record he cut in 1970 in Wesleyan, Connecticut that he recorded with some of the best sidemen in the business, only to finally listen to it and realize he couldn’t hear himself play; the lesson he took away from that was “Never let your dobro player get too high in the mix.” Later in the show he contrasted that experience with the happy one of playing with acoustic master Tommy Emmanuel quite by accident. Book Binder was doing a show and recognized Emmanuel near the stage. He went over to pay his respects and was surprised when Tommy vouchsafed that he was a huge fan of Roy’s—and had been since the 1960s. That took Book Binder quite by surprise, and then Tommy asked if he “might back him up for a song or too.” Roy thought well, here goes, he’ll steal the show, but at the same time he couldn’t say “no” to Tommy Emmanuel.

That’s when he found out what a pro and a gentleman Tommy was. He truly did stay in the background during both songs, and only played some quiet harmony to bring out the best in Roy’s playing. It was a joyful experience and made you appreciate that what makes a great musician is not always what they play, but what they don’t play—and how they know when to lay off, and to create instinctive arrangements that highlight the other performer. Roy’s show was filled with such moments of grace, of paying tribute to other artists and demonstrating points of musicianship that you would only hear in a master class. What a joy he was to listen to, both in playing and talking about the music.

However far he ranges in a show, Roy Book Binder always comes back to the guitar hero who brought him into the arena—the Reverend Gary Davis, who’s playing remains unsurpassed. His legendary Biblical song Samson and Delilah brought stardom to many a young Greenwich Village folkie, from Dave Van Ronk to Peter, Paul and Mary, who had a hit with it and originally claimed authorship, assuming it was traditional until word got back to the Reverend, and he stepped forth with a claim of copyright infringement. When the trio invited him to a business meeting with Warner Brothers Records to sort it all out, the business representatives from Warner asked Rev. Davis when he wrote it. Well, to their amazement he spoke right up and said, “I didn’t write it.”

As they breathed a collective sigh of relief and started counting their new royalty checks, Davis continued explaining, “The Lord revealed it to me one night in Harlem in 1957.”

You couldn’t argue with that, and Peter, Paul and Mary honorably signed over the songwriting royalties to Reverend Gary Davis. (Davis’s estate is represented by Manny Greenhill’s management company—now run by his son (my friend) Mitch Greenhill—Folklore Productions in Santa Monica who relayed this story to me many years ago. They also secured Davis’s royalties for the song Bob Dylan recorded on his first record—Baby Let Me Follow You Down—which Davis composed before getting religion when he still wrote and performed songs both sacred and profane.)

So when Roy Book Binder performed Samson and Delilah he introduced it with a few words in praise of “The House That Peter, Paul and Mary Built,” that got Reverend Davis off the streets and finally secured him a decent place to live. That’s what makes folk music different from other forms of music—it comes wrapped in these inimitable tales of survival and struggle—and compassion and generosity. For every song that Roy sings there is a behind-the-scenes story of human triumph over adversity. A singer like Roy Book Binder lives the life he sings about—and for nearly fifty years he has woven these songs and stories into the fabric of American life.

For his last song he dropped his “E” string to “D” and finger-picked a glorious version of Another Man Done Gone, a tribute to all who had come before him, and whose lives and music he now was tasked to carry on. He also wrote a lovely song he performed earlier—in tribute to Rev. Gary Davis, The Preacher’s Hands Danced Along the Strings. In Roy Book Binder’s weathered hands, the preacher is still dancing. Amen, Roy; amen.

“Road Scholar” was the title of Michael Cooney’s Sing Out! column for many years.

Ross Altman has a PhD in English; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com