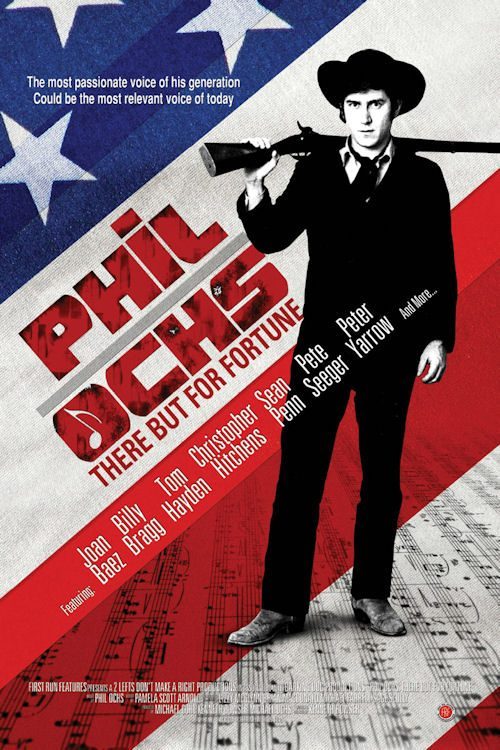

PHIL OCHS: THERE BUT FOR FORTUNE

Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune

A Documentary (2010) by Kenneth Bowser

Abbie Hoffman did it with pills, Jerry Rubin walked into an on-coming car on Wilshire Blvd., and Phil Ochs hung himself on his sister’s bathroom door in Far Rockaway, New York. All founders of the Yippies—the Youth International Party that confronted Mayor Daley and the Democratic Party at the Chicago Convention in 1968 and led to the Trial of the Chicago 7. All dead of suicide. So far as we know there was no suicide pact, but in the aftermath of the long strange trip of the 1960s, a more eerie coincidence would be hard to imagine were it not true.

Abbie Hoffman did it with pills, Jerry Rubin walked into an on-coming car on Wilshire Blvd., and Phil Ochs hung himself on his sister’s bathroom door in Far Rockaway, New York. All founders of the Yippies—the Youth International Party that confronted Mayor Daley and the Democratic Party at the Chicago Convention in 1968 and led to the Trial of the Chicago 7. All dead of suicide. So far as we know there was no suicide pact, but in the aftermath of the long strange trip of the 1960s, a more eerie coincidence would be hard to imagine were it not true.

Fortunately, some of the more eloquent voices of that volcanic decade made it out alive, and continue to bear witness to its courage, commitment and overzealous foibles that make it continually memorable into its half century anniversary this year. Perhaps its most eloquent voice did not, protest folk singer, songwriter, organizer and provocateur Phil Ochs, the subject of filmmaker Kenneth Bowser’s astonishing new documentary, Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune, which, for a week in August, 2010 was shown for an Academy Award qualifying run in New York and Los Angeles. before its official release in the beginning of 2011.

In its opening frames Phil Ochs sings a song that defines his greatness as an artist, both for its musicality and its intense lyricism, While I’m Here:

There’s no place in this world where I’ll belong when I’m gone

And I won’t know the right from the wrong when I’m gone

And you won’t find me singing on this song when I’m gone

So I guess I’ll have to do it while I’m here.

As tragic as his death was, brought on by a combination of alcohol and manic-depressive illness that runs in his family, described with utter candor in the movie by his devoted brother and co-producer of the film Michael Ochs—founder of the Michael Ochs Archives in Los Angeles—his music remains the most powerful soundtrack of the antiwar and civil rights movements that defined the decade and a joyous reminder of why Phil Ochs’ life retains its hold on our imaginations thirty-five years after he died. The Power and the Glory, I Ain’t Marching Anymore, the Ballad of Medgar Evers, Here’s To the State of Mississippi, Draft Dodger Rag, Love Me, I’m a Liberal, Outside of a Small Circle of Friends, the Crucifixion, Cops of the World, and There But for Fortune—were the history books of the period to go up in smoke, one could do a good job of reconstructing the highlights and low points of the decade with the Phil Ochs Songbook.

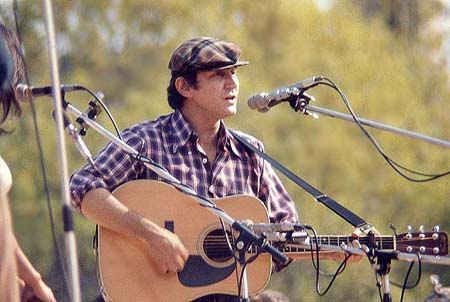

The sound quality of the movie is outstanding—Phil’s excellent finger-style guitar accompaniments on his old Gibson J-50 shimmer throughout, and his beautiful singing voice (until he was attacked and almost strangled to death in Africa in the early 70’s—which damaged his vocal chords and helped fuel his depression) is gloriously captured in one live performance after another, often in intimate settings far removed from the concert halls and mass demonstrations that were his usual venues.

Indeed, it was at one of those antiwar demonstrations in San Francisco that I was fortunate enough to hear Phil Ochs live, in 1967; he never turned down a request to sing at a demonstration, nor I am sure did he get paid for his constant presence in the antiwar movement, for whom he wrote the title song of his second album, I Ain’t Marching Anymore:

Oh I marched to the battle of New Orleans

At the end of the early British War

A young land started growing

And young blood started flowing

But I ain’t a’ marching anymore.

Many of his colleagues in the movement recalled both the highs and lows of Phil’s life, and helped to put it in illuminating historical perspectives. One of the Chicago Seven, Tom Hayden, described the 1960s as composed of two distinct periods, punctuated by the assassinations of JFK in 1963, before which a profound sense of hope and possibility was in the air that inspired and energized the civil rights movement, and of MLK and RFK in 1968, after which a malaise of despair clouded over the most determined efforts to achieve an end to the war and a new direction for the country. The four and a half years in between proved the testing ground for Phil’s growth as an artist, during which he began to expand his musical and poetic vocabulary as a songwriter, in ways that provided a distinct alternative to the folk rock pioneered by his Greenwich Village soul mate and rival for preeminence, Bob Dylan. When Bob went electric, Phil went classical, exploring accompaniments demonstrated by pianists Van Dyke Parks and Larry Marks, the latter of whom arranged Phil’s brilliant satire on the death of Kitty Genovese, Outside Of a Small Circle of Friends. This hit song was just one of a number that displayed Phil’s willingness to call them as he saw them and let the chips fall where they may:

Many of his colleagues in the movement recalled both the highs and lows of Phil’s life, and helped to put it in illuminating historical perspectives. One of the Chicago Seven, Tom Hayden, described the 1960s as composed of two distinct periods, punctuated by the assassinations of JFK in 1963, before which a profound sense of hope and possibility was in the air that inspired and energized the civil rights movement, and of MLK and RFK in 1968, after which a malaise of despair clouded over the most determined efforts to achieve an end to the war and a new direction for the country. The four and a half years in between proved the testing ground for Phil’s growth as an artist, during which he began to expand his musical and poetic vocabulary as a songwriter, in ways that provided a distinct alternative to the folk rock pioneered by his Greenwich Village soul mate and rival for preeminence, Bob Dylan. When Bob went electric, Phil went classical, exploring accompaniments demonstrated by pianists Van Dyke Parks and Larry Marks, the latter of whom arranged Phil’s brilliant satire on the death of Kitty Genovese, Outside Of a Small Circle of Friends. This hit song was just one of a number that displayed Phil’s willingness to call them as he saw them and let the chips fall where they may:

Smoking marijuana is more fun than drinking beer

But a friend of ours was captured and they gave him thirty years

maybe we should raise our voices/ask somebody why;

But demonstrations are a drag

Besides we’re much too high

And I’m sure it wouldn’t interest anybody outside of a small circle of friends.

He wasn’t in anybody’s pocket, and though identified with protest music in the broad (side) sense, as often as not his targets would have rankled those in the previous generation that gave rise to the name “Woody’s Children” to describe Phil, Dylan, Tom Paxton, Eric Andersen and others. For example, in Phil’s antiwar classic I Ain’t Marching Anymore he does not just go after corporations and politicians, but labor unions as well, when he writes,

Oh the labor leaders holler when they close the missile plants

United Fruit screams at the Cuban shore

Call it peace or call it treason

Call it love or call it reason

But I ain’t marching anymore.

In Pete Seeger’s generation, one did not dare call out labor unions for their complicity in the crimes of capitalism; Phil Ochs’ allegiance was to the people who were suffering—not to any preordained institutions.

And yet despite the generation gap between them, it is Pete Seeger who tells two of the most compelling stories about Phil in the film, one early and one late; before Dylan or Ochs had made their first records, Pete brought them up to the offices of Sis Cunningham’s and Gordon Friesen’s Broadside Magazine, which was set up to publish topical songs that didn’t quite fit in Sing Out! As Pete sat listening to the new songs Phil and Bob brought with them, all written within the past couple of weeks, Pete realized that he was hearing something he hadn’t heard since Woody Guthrie became hospitalized with Huntington’s Chorea—an outpouring of songs based on news stories that were fresh as today’s headlines. He concluded by the end of their “audition” that he was sitting with “two of the greatest songwriters in the world, only nobody knew it yet.”

The later story is even more gripping, the first time I have heard Pete recount in such chilling detail the final hours of the 3,000 students and workers imprisoned in the Estadio Chile during the coup on September 11, 1973, one of whom was folk singer and Nuevo Cancion songwriter Victor Jara, who had befriended Phil Ochs during his trip to Chile earlier that year. The film footage of Victor Jara is indeed one of the most significant revelations in the documentary, since it weaves Phil Ochs story into a hemisphere wide struggle involving the democratic socialist movement in Chile with the American artist most in tune with it, who reached out to Victor Jara before anyone else here but perhaps Pete Seeger recognized his greatness. Indeed Victor is referred to in the film as “the Pete Seeger of Chile.” To see Phil’s deep connection to him and the struggle for which he gave his life brings into sharp focus the vision of Ochs as an international artist who understood—and documented—world music before there was even a name for it.

Pete describes Victor Jara’s last minutes—on September 16—when his hands are crushed by the junta on a table displayed in the center of the stadium, much as a cross and its mutilated victim would have been erected on the roadside by ancient Romans to terrify its citizens into obedience. As the rifle butts come down on Jara’s delicate hands—that had fashioned his own guitar out of a walnut tree in his back yard—Pinochet’s henchmen scream at him, in Pete Seeger’s uncensored account, “Now play, you cocksucker!”

Jara then holds up his bloody stumps so the crowd can see what these soldiers have done, and starts leading them in song; before he is finished the soldiers take aim and murder the voice of Chile. Then the generals order their soldiers to turn their guns on the crowd, and massacre the movement that had elected Salvador Allende. While the blood of the people is flowing onto the stadium floor, Pinochet leaves in a chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce.

Back home in New York City, Phil Ochs took it very personally; he felt as though he had lost a brother. He also took it personally because he held his own country accountable, once he started connecting the dots from what he had personally observed during his trip and conversations with Victor and concluded that the CIA must have been involved in this horror, and by extension—the Department of State, headed by Dr. Henry Kissinger

Phil decided to do what he could to help the families of the “disappeared,” and organized a benefit concert for their relief. It was at that concert—which wound up being headlined by Bob Dylan, and provides some of the most moving footage in Kenneth Bowser’s amazing film, of Ochs and Dylan on stage together after several years of estrangement—that for the first time in public the CIA is implicated in the overthrow of a democratically elected government in our own hemisphere. The following morning the New York Times—the nation’s paper of record—reported the allegations based on what they had picked up at the concert, and the long slow emergence of a story now uniformly accepted as true was brought to light, by a topical folk singer who had first trained as a journalist, and wound up breaking the story of his life.

But there is much more than politics in Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune; the personal stories are equally remarkable and well told—his friend, poet and singer Ed Sanders is particularly eloquent when speaking of Phil’s battle with drugs, alcohol and mental illness. He describes the effect on Phil of his own terrible behavior during some of these episodes, which drove Dave Van Ronk away from any further contact with him. Ed puts it like this, “When you make mistakes of this magnitude, it leaves harpoons and fish hooks in your soul; you don’t get over it, nor do your friends. At this point Phil had even taken on another name—John Butler Train, insisting to all who would still listen that “Phil Ochs is dead—he doesn’t exist anymore.”

His songs took on the task of documenting his own despair, particularly after his trip to Africa had resulted in a violent attack that left his vocal chords permanently damaged so he lost three notes of his vocal range—which was particularly hard on an artist who had memorably said, “Ah but in such an ugly time, the true protest is beauty.” In No More Songs he writes,

Hello, hello, hello

Is there anybody home

I’ve only called to say I’m sorry

The drums are in the dawn

And all the voices gone

And it seems that there are no more songs.

As he reaches the end it is clear he is losing his will to live, and yet even so he articulates it in some of the most moving lines of his career:

A star is in the sky

It’s time to say goodbye

A whale is on the beach

He’s dying

A white flag in my hand

And a white bone in the sand

And it seems that there are no more songs.

As difficult as his own life was, and as difficult as he sometimes made others’, such as his wife Alice Ochs and their daughter Meegan, who Alice movingly describes as “the joy of Phil’s life,” one comes away from this loving but brutally honest story with a powerful sense of gratitude for the lasting music Phil managed to compose in both the highs and lows of his struggle to stay true to his well wrought artistic mission of a protest singer engaged with his times, who loved his country with a fierce determination to make her live up to his life-affirming values. Ochs was made a rebel by the war and by racism.

Most importantly, as Kenneth Bowser’s movie makes clear, Phil was not born a rebel—as was, for example one of his lifelong heroes whom he discovered in the movie houses of Ohio—James Dean, of whom he would later write,

His mother died when he was born

His father was a stranger

Marcus Winslow took him in

Nobody seemed to want him…

He played a boy without a home

Torn with no tomorrow

Reaching out to touch someone

A stranger in the shadow.

Jim Dean of Indiana

Unlike James Dean, Phil did his best to fit in: he went to a military academy and intended to pursue a military career, only leaving when he thought that journalism would be more to his liking, which led him to Ohio State, where he roomed with folk musician Jim Glover. That is where he stumbled on Jim’s guitar, and where a fellow Ohio State student (and personal friend of mine, the late Fred Starner) gave him his first guitar lessons.

Phil got into a bet with Jim, for which Glover put up his Kay Guitar as collateral, and proceeded to lose the bet and the guitar. Phil Ochs thus acquired his first guitar, though he was already a trained musician who had studied both clarinet and piano as a high school student. Jim bought a better guitar and eventually teamed up with his girlfriend Jean to become the recording duo, Jim and Jean, whose first album was called Changes, the lyrical title song that Phil wrote in 1965 and recorded himself for his first live recording at Carnegie Hall. Its haunting images endure,

Scenes of my young years

Grow warm in my mind

Visions of shadows that shine

Till one day I return

And find I was the victim of the vine of changes.

From the beginning Phil Ochs had a sense that time was closing in, that, as Wordsworth once wrote, “Nothing can bring back the splendor in the grass” and that, “a poet’s life begins in gladness and ends in madness.”

What remains, and what makes it meaningful, is the unequalled body of songs that document a time when freedom and justice and peace were not just words on an opportunistic politician’s tongue, or code words for their opposites in a demagogue’s cable TV show, but the objects of a great artist’s life and death struggle.

As the closing credits roll, over contributor’s names that include cultural critic Christopher Hitchens, Joan Baez, Judy Henske, and his sister Sonny Ochs, one sees and hears his once estranged friend, whose heart with many others was broken at the news of Phil’s death at 35, singing, He Was a Friend of Mine. Dave Van Ronk spoke for us all.

Ross Altman has a Ph.D. in English. Before becoming a full-time folk singer he taught college English and Speech. He now sings around California for libraries, unions, schools, political groups and folk festivals. You can reach Ross at Greygoosemusic@aol.com