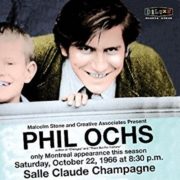

PHIL OCHS – LIVE IN MONTREAL 10/22/66

TITLE: PHIL OCHS LIVE IN MONTREAL 10/22/66

ARTIST: PHIL OCHS

LABEL: ROCKBEAT RECORDS

RELEASE DATE: MAY 5, 2017

The Unquiet American

“The death of the poet was kept from his poems” ~ W.H. Auden In Memory of W.B. Yeats

“The death of the poet was kept from his poems” ~ W.H. Auden In Memory of W.B. Yeats

“When I’m Gone” by Phil Ochs

There’s no place in this world where I’ll belong when I’m gone

And I won’t know the right from the wrong when I’m gone

And you won’t find me singing on this song when I’m gone

So I guess I’ll have to do it while I’m here.

Ochs may have underestimated himself, because every few years another testament and example of his ongoing presence in our lives surfaces from the depths like a submarine.

Michael Simmons, author of the liner notes for this first-time release of Phil Ochs: Live in Montreal 10/22/66, Ochs’ 1966 concert in Montreal, Canada, makes every effort to bring Phil kicking and screaming into the 21st Century—indeed the Age of Trump. What would it be like if Phil were here to take on this regime as he did Johnson and Nixon? “What Would Phil Do?” asks Simmons and then creates a brilliant portrait of the artist as a young man, before the depression, alcoholism and near-psychosis when he changed his identity to “John Butler Train” and eventually reached his personal crossroads on April 9, 1976, and took his own life. This concert took place ten years before that—before he declared The War Is Over, and before he finally declared there are “No More Songs.” October 22, 1966 was in the heart of his genius and youthful optimism—and he gave a great concert that reflected the full range of his songwriting talent—including between songs commentary that created an on-gong conversation with his audience of a devastating wit. As Simmons points out, this concert also represents a watershed moment when Phil was at a turning point between his last Elektra album (Phil Ochs in Concert) in 1966, the “lone troubadour” with just a guitar onstage and his more elaborate and eclectic arrangements that included ragtime and classical instrumentation—by Van Dyke Parks—(Pleasures of the Harbor) he would bring to A & M Records in 1967.

But the core question Simmons raises is what Ochs might have done to stop Trump~ and the answer unfortunately is it would hardly have mattered. Of course he may have written songs—despite the fact that he had already declared there were “no more songs.” He might have declared that “Trump is Over” despite the fact that his declaration “The War is Over” was made in 1968—and the war wasn’t really over until 1975. The truth of what folk singers do is better reflected by W.H. Auden’s observation in his elegy to W.B. Yeats,

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flow on south

From ranches of isolation and busy griefs

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives

A way of happening, a mouth.

A bitter pill to swallow to those of us who believe that a song can change the world, but Auden wouldn’t sugarcoat it. When he came to the conclusion that his most famous poem—September 1, 1939—was not telling the truth—in its resonant line “We must love one another or die”—because he had to admit “We would die anyway,” he deleted the entire poem from his Collected Poems. That is artistic integrity, summed up in his line from another poem: “Nothing is lovely—not even in poetry—that is not the case.” (vs. Keats’ “Beauty is truth, truth beauty…”)

However, Auden—the greatest Anglo-American poet of the 20th Century–does not have the last word on this subject. Phil Ochs–the greatest American protest poet of the 20th Century—does. For it was Phil Ochs who found the sliver of light in the failure of the New Left to end the War in Vietnam. Phil Ochs said, “Ah, but in such an ugly time, the true protest is Beauty.” And that is what Phil Ochs created—beauty unsurpassed—beyond all the declarative statements about the War and many other topics—the beauty of his lyrics and the beauty of his music—and that is what is most fully documented in this buried treasure of an almost lost recording from October 22, 1966. It’s an amazing concert with 20 amazing songs that should win a Grammy—and it will survive long after the current hoax Simmons sums up as “a neo-fascist con man with gilded hair and gilded toilet seats” who now occupies the White House is relegated to the dustbin of history.

More than anything, what this concert reveals is the enormity of the tragedy of Phil Ochs giving up on life when he did. At some time—perhaps now more likely than ever—he would have found his voice again and prompted Americans to Lincoln’s better angels of our nature. For unlike most of the “protest” singers around at the time he was a true American patriot, who began as a cadet in Virginia’s Staunton Military Academy; he loved his country—as is evidenced by his passionate poetic masterpiece Crucifixion—his second song for JFK after the assassination (referenced by Michael Simmons in his eloquent, illuminating and extraordinary liner notes—which are worthy of Phil’s songs and should also be awarded a Grammy for historic value next February). Phil Ochs—after satirizing Kennedy with Talking Cuban Crisis in October, 1962—was the first folk singer of the folk revival to pay homage to him after November 22, 1963, with the song That Was the President:

How a man so filled with life, even death was caught off guard.

Crucifixion is copyrighted 1966, the same year as this landmark Montreal concert:

So dance, dance, dance

Teach us to be true

Dance, dance, dance

’Cause we love you.

At the same time he satirizes Christianity in the Canons of Christianity—and in this double CD on a song here released for the first time, Chaplain of the War—he uses its most famous symbol to represent the slain president. “I contradict myself,” said Walt Whitman, “very well I contradict myself/I am large—I contain multitudes.” Like Whitman, Ochs contained multitudes. His songs were not written to a prescription or to be consistent to some rigid preexisting belief system—they were written to be honest to his feelings when he wrote them. That is why they endure. They are always art—not propaganda. That is his core belief and what underlies his diehard principle “The true protest is beauty.”

There is another Michael behind this recovered masterpiece—Phil Ochs’ younger brother Michael Ochs. “Am I my brother’s keeper?” asked Cain, with the intent to disparage the idea. But Michael has been his brother’s keeper without apology or misgiving; and here he brings to life his brother’s voice once again—the presentation is itself a thing of beauty—a double CD/20 songs packaged to mimic an 33rpm LP with the first CD labeled “Side A” and the second “Side B.” Give the label Rockbeat credit too, for the perfectly realized black & white color scheme of the CD face art—produced by Michael Ochs; Mastering Randy Perry; Art Direction/Design Mark Kalmus; here are the track listings:

Disc 1:

1) Cross My Heart

2) Song of My Returning

3) The Bells

4) Flower Lady

5) Miranda

6) Joe Hill

7) I’m Going to Say It Now

8) Pleasures of the Harbor

9) I Ain’t Marching Anymore

10) Outside of a Small of Friends

11) I’ve Had Her

Disc 2

1) There But for Fortune

2) Cops of the World

3) Crucifixion

4) Is There Anybody Here?

5) Changes

6) Party

7) Doesn’t Lenny Live Here Anymore?

8) Power and the Glory

9) Chaplain of the War

Words and Music by Phil Ochs All songs © Barricade Music, Inc.

I saw Phil Ochs live once—and have never forgotten it. Fifty years ago this summer—the Summer of Love in 1967—at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. I wore no flowers in my hair, and did not drive four hundred miles for a love-in—but for an anti-war march. For several hours there were high quality speakers—and except for Buddhist philosopher Alan Watts I don’t remember a single one of them. But I remember Phil Ochs—who sang towards the end and brought his impassioned anti-war songs like the one he sang in Montreal—I Ain’t Marching Anymore. He also dedicated I’m Going to Say It Now to Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement leader Mario Savio—as he does on this concert recording—by name. Like Savio, Phil Ochs was the unquiet American—loyal opposition to leaders whom British novelist Graham Greene called The Quiet American—portrayed by Michael Caine in the movie adaptation. Phil Ochs gave voice to a generation of dissenters who refused induction, refused to cooperate with a murderous unjust war on impoverished peasants, and refused to be cowed by the collective power of the State.

“I never should have loaned this guitar to Dylan,” Ochs quips at the beginning of Side B, while he attempts to tune it for There But For Fortune and it proves recalcitrant. To bring his name into the concert reminds his audience where he comes from—the Greenwich Village folk scene. And it also reminds them that no one else would have been in that position. But even more delightful is the quip from Side A introducing The Bells~ he refers to “a prominent protest songwriter today”—and while everyone awaits the mention of Dylan’s name—Ochs pauses and says “Edgar Allan Poe,” father of the New Left to another rousing response of laughter. The audience throughout is having a great time—and not just from the songs—but Ochs standup comedy between; beautiful!

“As you know I’m a folk singer for the FBI,” he pauses again before starting “The Crucifixion”—about the Kennedy assassination.” What I wouldn’t give to be able to hear him sing it again—during the Centennial of JFK—born May 29, 1917. But wait a minute! Thanks to this concert, recorded as Michael Simmons notes, just one month before the third anniversary of that fateful day, I can hear Ochs sing it again, and so can you. What a gift! Phil Ochs was the troubadour of Kennedy’s memory, and outside of Arlington it remains the greatest song to keep that eternal flame brightly burning.

One of the singular features of this glorious concert recording is the relation of Phil Ochs to his Montreal audience at Salle Claude Champagne. He reaches out to them—knowing it is a French-speaking audience, who are nonetheless immediately conversant with his songs and speech—in a more comprehensive way than he might have done for a hometown audience in New York City. He contextualizes the songs in a meaningful way—as when he says that Joe Hill was a “minor hero” of the labor movement as a songwriter for the Industrial Workers of the World—the Wobblies—until he was indicted for murder in Salt Lake City, Utah, when he became “a major hero.” That is a brilliant observation I’ve never heard any other performer articulate. And then he places the music of his ballad to place himself in the folk tradition as well—pointing out it is to the music of the traditional song “John Hardy.” It’s a quiet, moving and profound introduction that shows his music belongs in a particular historical tradition—it grows out of American folk music. It’s worth the price of admission—only $2.75—yet another sign of the times.

So whatever Phil Ochs would do—in Michael Simmons provocative question—were he able to return to the Theatre of the Absurd American political struggle today, I feel secure in saying one thing—he would not be doing cover songs of Frank Sinatra. Ochs’ time—as Simmons’ notes intimate—would have been now. He would have been the voice, the heart, the mind and sensibility we would have turned to in the oppressive conditions of Trump’s America—like the man who created the benefit concert for Chile after the coup.

But that was yet to come. After the explosive and enduring ovation he receives after his closing song The Party, he suddenly returns to the microphone and evokes his longstanding comrade in arms with the gravelly words and notes,

You’ve got a lot of nerve to say you are my friend…

from Positively 4th Street. The audience once again breaks up in familiar laughter. Phil then gets serious and lets them know that for an encore he will do “a song I just finished writing last week,” as he launches into Doesn’t Lenny Live Here Anymore? He never mentions his last name, but its power and the forlorn grief of its poetry screams out “Lenny Bruce” from every verse. It made me wonder how long before the concert Bruce had died from a heroin overdose; and sure enough, it was only two months before—August 3, 1966. Phil Ochs eulogized and memorialized him with all the aching power of a fellow social satirist who may have felt he had lost his older brother—a brilliant, sad tribute to the prophetic, persecuted comic.

“What would Phil do?” You don’t have to wonder—he would have thundered like Amos, he would have lit one candle in the darkness like Bobby Kennedy, he would have fought like Joshua, he would have played his old acoustic Gibson guitar and sung his heart out—“until justice rolled down like water, and righteousness like a might stream.”

And he would have come out for his second encore, just like he did at this amazing and blazing concert of his best songs and his newest songs, when the audience would not stop applauding and screaming like it wasn’t just a protest singer up there, or even Dylan, but the Beatles. When Phil suddenly turns back to the microphone and says tongue-in-cheek “fooled you~” they started screaming even louder and shouting requests. Phil responds to the request for his early and beloved patriotic anthem—the song he thought to be his best—The Power and the Glory—which he had written while staying at his sister Sonny Ochs’ home in Far Rockaway, New York. She came home and heard his Beethoven-like descending opening four notes—as recognizable as the opening to the 5th Symphony—and asked her brother what he was doing. “I’ve just written my greatest song,” replied Phil. “What’s it called?” inquired Sonny. “I don’t know—I haven’t written the words yet.” That’s what distinguishes Phil Ochs from all of his contemporaries; he spoke through his music as well as the words to his songs. He knew he had written a great song before he had written a word—the notes told him that. The melody carried the poetry. That is why he could say, “Ah, but in such an ugly time, the true protest is beauty.”

And yet the power and the glory of Phil Ochs’ music is often intensified by its dramatic tension with his lyrics. Outside of a Small Circle of Friends is a jaunty, ragtime setting for a tragic, cynical tale of the murder of Kitty Genovese in New York City—which had compelled his attention for a long time—a tale of indifference from the bystanders. The contrast between the music and lyrics highlights their complicity in the crime. And his antiwar I Ain’t Marching Anymore is a march tune worthy of John Philip Sousa.

Phil started out as one of Woody’s Children. How many folk protest singers today claim him as their spiritual father? Every sanctuary city in this “green and growing land” has one; As Auden wrote of Yeats: he became his admirers. Now he is scattered among a hundred cities.

But “The death of a rebel,” his line from Joe Hill and the title of his first biography by Marc Eliot (Anchor Books/Doubleday 1979) was kept from his songs.

So, dear Reader, if you have been searching for insight, illumination, and above all for hope in this current ugly time, search no further—you don’t need to look back; Phil Ochs could have given this immensely joyful noise unto the Lord yesterday. How fortunate we are to have it now. Thank you to Michael Ochs and Michael Simmons and Rockbeat Records for making it possible. And thank you Phil Ochs, for listening to America, and having found your voice in her own. “It takes a great audience,” said Walt Whitman, “to make a great poet.” In Montreal, Phil Ochs found a great audience; probably including young Americans who had gone into exile in Canada rather than serve in Vietnam or go to prison~ and they found a great poet. We are their lasting, permanent beneficiaries.

We know what Phil would do. The question for us now is…what would we do?

Afterword:

~Dedicated to Phil’s grandson Caiden Lee Ochs~

Phil’s late wife Alice passed away in 2010; their daughter Meegan Lee Ochs works for the ACLU and carries on the work of social justice very much in the spirit of her father. His sister Sonny carries on annual tribute concerts and a web site devoted to his music. And his brother Michael created the Michael Ochs Archives, Ltd. which makes original music photographs available to record labels, books, magazines, museums, filmmakers and TV programs around the world—it’s the major repository of such photos and has helped to educate successive generations about the music of Phil Ochs’ generation and beyond. Michael produced the documentary feature Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune.

For a basic Phil Ochs sampler see the two-record memorial album Chords of Fame and accompanying songbook of the same title, released by A & M with the cooperation of Elektra Records in 1976. See also Vanguard Records Phil Ochs—The Early Years, released in 2000. And see also Phil Ochs Sings for Broadside on Smithsonian Folkways.

Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature from SUNY-Binghamton; he belongs to Local 47 (AFM); Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com