PASSION PLAY 2014

Passion Play 2014: Bound for Glory

Shepherd of the Hills Church, Porter Ranch, California

Palm Sunday, April 13, 2014

“I saw Jesus on the cross/On that hill called Calvary/Do you hate mankind for what they’ve done to you?/He said talk of love not hate/Things to do it’s getting late/We’re all brothers and we’re only passing through.” A song from a Catholic hymnal? A Protestant prayer book? Not even close: it’s from Lift Every Voice, the second left wing People's Songbook of 1953, the same book that contained songs by the soon-to-be blacklisted Pete Seeger, suspected communist Paul Robeson, executed IWW troubadour Joe Hill and Dust Bowl Balladeer Woody Guthrie. It was written by a professor of Renaissance Literature at Cal State Northridge and People’s songster, Dick Blakeslee. What’s a Godless commie folk singer doing writing songs about Jesus? Maybe because Jesus was himself a textbook case of a radical misfit. Who said “The meek shall inherit the earth.”? Who said, “As you do unto the least among us, you do unto me”? Who said “What shall it profit a man to gain the whole world and lose his own soul.”? Who drove the money changers out of the temple? Hint: it wasn’t Karl Marx, who wrote The Communist Manifesto in the safe confines of the British Museum’s Reading Room. So what kind of a man was Jesus?

“I saw Jesus on the cross/On that hill called Calvary/Do you hate mankind for what they’ve done to you?/He said talk of love not hate/Things to do it’s getting late/We’re all brothers and we’re only passing through.” A song from a Catholic hymnal? A Protestant prayer book? Not even close: it’s from Lift Every Voice, the second left wing People's Songbook of 1953, the same book that contained songs by the soon-to-be blacklisted Pete Seeger, suspected communist Paul Robeson, executed IWW troubadour Joe Hill and Dust Bowl Balladeer Woody Guthrie. It was written by a professor of Renaissance Literature at Cal State Northridge and People’s songster, Dick Blakeslee. What’s a Godless commie folk singer doing writing songs about Jesus? Maybe because Jesus was himself a textbook case of a radical misfit. Who said “The meek shall inherit the earth.”? Who said, “As you do unto the least among us, you do unto me”? Who said “What shall it profit a man to gain the whole world and lose his own soul.”? Who drove the money changers out of the temple? Hint: it wasn’t Karl Marx, who wrote The Communist Manifesto in the safe confines of the British Museum’s Reading Room. So what kind of a man was Jesus?

I wanted to find out for myself, so I figured where better than the best passion play in town, which Jill and I had the good fortune to see last night at the sold-out production of The Passion Play at Shepherd of the Hills Church in Porter Ranch, with a cast of hundreds, including children, teens and adults, some of them highly esteemed Hollywood professionals. If you want to see a passion play, theirs is the production to see.

Shh…don’t tell my rabbi. Speaking of whom, how many times in this play was Jesus addressed as “Rabbi this, and Rabbi that?” One might almost think that Jesus was a Jew. Oh, right.

From their web site here are the basic credits: "The Passion Play" is directed by Chip Hurd, director of Tyler Perry's House Of Payne and the award-winning audio Bible, The Bible Experience. Jasper Randall, choir conductor and vocal contractor for the Academy Award-winning animated films Avatar and Tangled, has written a dynamic score for the production, featuring recording artist Cindy Herron-Braggs from EnVogue. Musical direction is by Maxi Anderson whose vocals can be heard on the movies Happy Feet Two and Ides of March with George Clooney.” And here is their synopsis: “The story of Christ unfolds with timeless moments that touch the heart. This musical production shares the story of Jesus from his birth to his life's ministry. We witness the power of his healing, the depths of his love for the hurting and the cost of that love when he is nailed to the cross. ‘The Passion Play’ leaves us with the loving and forgiving message of redemption.”

(A notable departure from this chronological storytelling was director Chip Hurd’s brilliant artistic choice to reserve the birth of the baby Jesus until the middle of the play; it thus introduces the final chapter that begins with Palm Sunday.)

Starring James Runcom as Jesus, let me add that it was lavish, spectacular, musically uplifting, elegant, beautiful and inspiring all at the same time. We had read the Bible before, but last night in their glorious version of the life and death of Jesus Christ we saw and heard it come to life. Shepherd of the Hills’ The Passion Play was both great drama and great music (with many of the songs composed by music producer and arranger Jasper Randall) from beginning to end. In the church sanctuary converted into a theatre holding 1500 people, the stagecraft was thrilling. But for those (like us, until last night) who may have never seen one performed, what is a passion play?

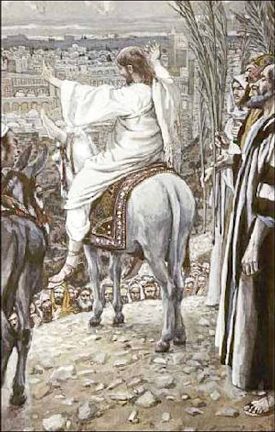

A passion play tells the story of Jesus’ life during his final fateful week, from the juxtaposition of his triumphant entrance into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, to his trial, conviction and Crucifixion on Good Friday, and Resurrection on Easter Sunday. Versions of it are centuries old and international in scope; there are Passion Plays from every country where Christianity has taken hold. There are Passion Plays in every state in this union—Red and Blue.

The most notorious version of the story was told in Mel Gibson’s blockbuster film The Passion of the Christ—notorious because it fell victim to the propensity for anti-Semitic portrayals of Jews as Christ killers. No surprise there: Mel Gibson was a public and extremely offensive anti-Semite on record for both his support of his father’s longstanding denial of the Holocaust and for his anti-Semitic and misogynistic encounter with the Malibu Police Department during a drunk-driving arrest five years ago. It was during that arrest that he charged Jews with “starting all the wars in the world” in addition to killing Christ. He also referred to the arresting female office as “Sugar Tits.”

It’s a hard image to get out of one’s mind when thinking about an ordinary non-celebrity version of the passion play. Rest assured, the Shepherd of the Hills family version (only children under six are not permitted) of the story is far removed from this tawdry record of racial prejudice and ethnic slander. It tells the story of Christ as a positive role model without scapegoating one religious group to account for his tragic end on the Cross. It also celebrates his most poignant moments during his life’s ministry, including the Sermon on the Mount. While it is clearly intended for believers, non-believers—even Jewish non-believers like me—will not find it offensive, as I did not.

And it does live up to its one-time Hollywood billing as “The Greatest Story Ever Told”. Yet why should all this matter to an audience of folk music fans? Because, in addition to being (according to Christians) the Savior of mankind, in addition to being the Son of God, in addition to being the Son of Man, Jesus is also a perennial folk hero, and folk heroes are the subject of folk ballads, from time immemorial. And folk ballads are the subject that ought not to escape any folk singer or folklorist’s attention, mine included.

Woody Guthrie wrote a memorable version of the story in his outlaw ballad, Jesus Christ, using the tune of Jesse James to drive the point home: “Jesus was a man/A carpenter by hand/A carpenter true and brave/But a dirty little coward called Judas Iscariot/Has laid Jesus Christ in his grave.” Like Jesse James he gave his life in service to poor people.

Woody Guthrie wrote a memorable version of the story in his outlaw ballad, Jesus Christ, using the tune of Jesse James to drive the point home: “Jesus was a man/A carpenter by hand/A carpenter true and brave/But a dirty little coward called Judas Iscariot/Has laid Jesus Christ in his grave.” Like Jesse James he gave his life in service to poor people.

Leadbelly too sang his own version of the passion story: “They hung Him on the Cross/They hung Him on the Cross/They hung Him on the Cross for me/One day when I was lost/They hung Him on the Cross/And He Never Said a Mumblin’ Word for Me.”

Bob Dylan, long before his Christian period began with the album Slow Train Coming, harkened back to the image of Jesus crucified in both his classic antiwar songs With God On Our Side and Masters of War; from the first song the lines: “Through many dark hours/I been thinkin’ about this/That Jesus Christ was betrayed by a kiss/But I can’t think for you/You’ll have to decide/Whether Judas Iscariot/Had God on His side.” And from the second: “Like Judas of old/You lie and deceive/A world war can be won/You want me to believe/But I see through your eyes/And I see through your brain/Like I see through the water/That runs down my drain… How much do I know/To talk out of turn?/You might say that I’m young/You might say I’m unlearned/But there’s one thing I know/Though I’m younger than you/Even Jesus would never forgive what you do.” His last line is particularly powerful, zeroing in on Jesus on the Cross and evoking his best-known single line: “Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do.”

Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Bob Dylan—our three greatest folk singers—and none of them religious zealots—have all responded to the sheer poetry of the Christ story—the poetry and its folk heroic drama.

That is what brought me to this passion play on Palm Sunday at The Shepherd of the Hills Church; that and a donkey: G. K. Chesterton’s narrator in his greatest poem:

The Donkey

by G. K. Chesterton

When fishes flew and forests walked

And figs grew upon thorn,

Some moment when the moon was blood

Then surely I was born;

With monstrous head and sickening cry

And ears like errant wings,

The devil’s walking parody

On all four-footed things.

The tattered outlaw of the earth,

Of ancient crooked will;

Starve, scourge, deride me: I am dumb,

I keep my secret still.

Fools! For I also had my hour;

One far fierce hour and sweet:

There was a shout about my ears,

And palms before my feet

Leave it to Chesterton to tell the story of Jesus from the point of view of the donkey he rode into Jerusalem, to remind people that “As you do unto the least among us, you do unto me.” Well, the donkey stole the show. Jack Lemmon once said, “Never do a play with a dog; he’ll steal every scene he’s in.” He knew what he was talking about. I was expecting and would have been satisfied with the oft-seen theatrical imitation of such four-footed creatures—a man with a mask in front, and one with a tacked-on tail in back, covered with a brown blanket and the rider on top of a board in the middle, all seen through the lens of Keats’s willing suspension of disbelief. You get the picture. But Shepherd of the Hills production was no bargain basement low rent Passion Play—it was a fully-mounted uptown “Broadway Musical” wherein Jesus rode a real donkey down the long aisle triumphantly into Jerusalem on stage—and on Palm Sunday no less—the date I chose to take Jill to see the play, specifically for this reason. As the donkey exited downstage right we were close enough to reach out and touch him. That would have been the last temptation of Ross; I resisted.

And, as I knew it would—spoiler alert!—it all went south from there, resulting in Judas Iscariot’s betrayal foretold at the end of their Passover Seder—The Last Supper—where Western Civilization’s first paid Informer identifies Jesus to the Romans with a kiss—for which he was paid thirty pieces of silver, followed by Pontius Pilate’s conducting Western Civilization’s first Inquisition. Pilate wrestles mightily with his conscience and almost gives one hope that the end will be different, but you know it won’t as—spoiler alert #2—he finally yells out decisively, “Crucify Him!”

Every stage of the Cross is dramatized eloquently and when the pitch-perfect actor playing Jesus—James Runcom—is—in the words of Leadbelly’s song—whipped up the hill, and speared in the side, and nailed to the cross, you can’t help but feel his excruciating anguish, as you actually see, again in Leadbelly’s words, “And the blood came streaming down.” If seeing is believing, Shepherd of the Hills Church’s glorious and sumptuous production of the Passion Play made a believer out of me. It unfolded, as I mentioned, like a Broadway musical, and the songs carried the narrative forward. They were beautifully sung and as I observed most of the great soloists were black performers. So now would be the time to underscore that the entire cast of hundreds looked like America—as did the thoroughly racially integrated audience. Every ethnic group was well-represented—no token actors here—with Asians, Blacks, Latinos and Anglos, and age groups as well with children, teens, and adults in both starring and supporting roles.

Among many revelations, that itself was a revelation. I have been to so many folk concerts where one is lucky to find any minorities in the audience—even when the world view of the performer—the best example, of course, being Pete Seeger—is of a world of many colors—as Cesar Chavez’s favorite song De Colores says so movingly. But without making any explicit reference to the ethnic, racial and inter-generational diversity of both cast and audience, this very Christian production showed why Christianity has been such a successful religion—it is all-inclusive.

There are times when it plays like Jesus’ Greatest Hits: you see him heal the sick, raise the dead and forgive the young adulterer with words that have since become routine at the end of every Catholic confessional “Go and sin no more,” but which for Jesus struck like lightning as the announcement of a new concept in the history of religion—the New Testament’s belief in Mercy to temper the Old Testament’s emphasis on Justice. He saves her life from the mob ready to descend on her with words that have become the benchmark of tolerance for the sinner, even as we may judge the sin: “Let he who is without sin among you, cast the first stone.” Too bad Jesus’ wise words have yet to penetrate certain parts of the world where even today a woman may be stoned to death with the full countenance of religious and judicial authority. This Passion Play is thus still timely as well as timeless.

We see and hear Jesus recite the Lord’s Prayer in the Sermon on the Mount, in response to someone in the audience’s asking Him, “Lord, teach us how to pray.” And again, what for Jesus was a moment’s inspiration—just an example really of how it might be done—has now become memorized by rote and passed on as scripture. For Jesus it was jazz-like improvisation and, like Ray Charles, he probably never prayed the same way twice.

He drives the money-changers from the Temple, practices what he preaches, lets the little children lead them, and tells us, “Blessed are the peacemakers.” And at the end—spoiler alert #3—when nailed to the cross he is heard to say the words Bob Dylan evoked in his greatest antiwar song, “Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do.” And then he looks up toward Heaven like Marlon Brando at the end of On the Waterfront and exclaims, “Why hast Thou forsaken me?”

Immortal he may have been, the Son of God he may have been, but like the Son of Man he also was, even Jesus had his doubts. It’s a profound moment in the Greatest Story Ever Told, showing that Jesus on the Cross was profoundly human as well as Godlike; or God, depending on your faith, or reasonable doubt.

But it doesn’t end there; he is buried in the tomb and three days later, well… I don’t want to give away the ending. This is really one you need to see for yourself. I don’t care what religion you are, Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Hindu, Zen Buddhist, Muslim, Atheist, or Woody’s “all or none,” you will revel in the seamless storytelling, the soaring vocals from all of the soloists, and the astonishing recreations of events you may think you have seen in your mind’s eye, or even on film, but trust me—you will see it all anew at Shepherd of the Hills The Passion Play 2014—as if for the first time.

I urge you to leave your preconceptions at the door—and have a wonderful time as we did. If you go on Good Friday or next Saturday you will have the additional treat of hearing a great modern Gospel song, Midnight Cry sung by soloist Tony Galla backed up by the entire cast on stage. But a word to the wise, this epic show is complete unto itself. Oh hell: spoiler alert #4: The Resurrection is a hard act to follow. Our thunderous standing ovation proved to me that this train indeed is bound for glory. Get on board, little children, get on board.

Thank you to Communications Director Monica Williams for complimentary second row aisle seats.

Shepherd of the Hills Church’s The Passion Play continues through Saturday, April 19; weekday tickets are $10; weekend $15-$20; for tickets and further information see www.The Shepherd.org. Tickets may be purchased on-line at www.sheptix.org.

Ross Altman presents Sing Out for Pete! at the Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest and Folk Festival, Sunday, May 18 at 4:30pm on the Railroad Stage; Paramount Ranch 2903 Cornell Road, Agoura Hills, California 91301; 805-370-2301.

On Saturday, May 31 Ross presents a concert and protest song workshop at the Claremont Folk Festival at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden. 10:00am-9:00pm. General admission tickets $40.

Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com.