MY DUSTY ROAD – WOODY GUTHRIE

TITLE: MY DUSTY ROAD

ARTIST: WOODY GUTHRIE

LABEL: ROUNDER RECORDS

RELEASE DATE: 2009

This essay is affectionately dedicated to Earl and Linda Thompson of Claremont, who gave me this beautiful boxed set, thinking it might grab my attention. Thank you!

In 2009, three years before the Woody Guthrie Centennial, Rounder Records released what Nora Guthrie describes as the definitive collection of Woody Guthrie songs in one collection; a handsomely mounted box set with an authoritative book length introduction to the artist and the tracks—one for nearly every year of his foreshortened life due to Huntington’s Disease. He lived to be 55, but for all intents and purposes his creative life lasted roughly 10 years, from the age of 27, when he was first recorded by Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress, to 38, when he was first admitted to Brooklyn State Hospital for the genetic illness that killed his mother.

In 2009, three years before the Woody Guthrie Centennial, Rounder Records released what Nora Guthrie describes as the definitive collection of Woody Guthrie songs in one collection; a handsomely mounted box set with an authoritative book length introduction to the artist and the tracks—one for nearly every year of his foreshortened life due to Huntington’s Disease. He lived to be 55, but for all intents and purposes his creative life lasted roughly 10 years, from the age of 27, when he was first recorded by Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress, to 38, when he was first admitted to Brooklyn State Hospital for the genetic illness that killed his mother.

In those eleven years he wrote—at first estimated as 1000 songs—now more likely to have been three thousand. Many of them were only preserved as lyrics, which his daughter Nora has been putting in the hands of modern folk singers and rock bands to add music and bring to life as songs. If you multiply ten years by the number of days in a year, it roughly translates to Woody having averaged a song a day for his entire creative life—a number so astonishing as to beggar description and defy belief.

Many of the songs in this collection are known worldwide as emblems of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression—songs that earned him the title bestowed on him by Alan Lomax: The Dustbowl Balladeer. His daughter Nora has been trying to change that way of seeing her father, by showing how many were the subjects that engaged his attention and which he transformed into songs. So be it. But in some sense it’s rather like showing that Thomas Jefferson was an extraordinary farmer—which he was—in addition to having written the Declaration of Independence.

Once someone is fixed in our imagination and history it is hard to dislodge him. And Woody is clearly up on the Mount Rushmore of American folk music—with Leadbelly, Pete Seeger, and Joe Hill. If you think of American folk music as a creative landscape, a country if you will, Woody Guthrie is the Father of our Country. He is the artist who more than any other made it a national music, and not just a regional expression of folkways. That is why so much attention is being paid to his Centennial—as if he were not just a great folk singer, which obviously he is, but a great writer—a member of a different pantheon altogether—along with such voices as Walt Whitman, Robert Frost, or, to take a more contemporary example, Jack Kerouac, author of On the Road and the father of the Beats.

Indeed, I would say that Kerouac is but one of the highly regarded writers who owed Woody Guthrie a permanent debt; his autobiography Bound for Glory (1941) could as well have been entitled On the Road, along with his collection of Dust Bowl Ballads from the year before. If anyone’s life was both lived and written on the road—in some ways the principal metaphor of American literature from Huck Finn to The Grapes of Wrath— it was Woody Guthrie’s. Like Robert Frost, his was the road not taken.

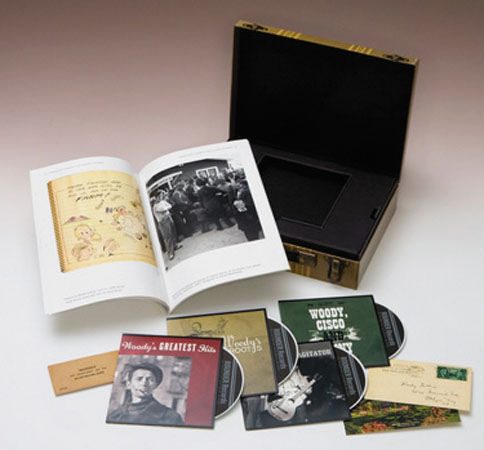

Indeed, three years before the Centennial, Rounder Records released this omnibus Woody Guthrie collection and put their finger on the central symbol of his work in the title: My Dusty Road, even presenting it in a scaled down suitcase for emphasis. It even includes his business card, evoking images of Paladin, as if Woody’s calling card might say: Have Song, Will Travel.

With so much symbolism hovering around him, is it still possible to just review an album? I’m not sure, but I will try. As a way in, it may be useful to demythologize Mr. Guthrie just a tad, to try and recover the man who actually wrote some of these songs, before he became a legend. Take for example the great sequence of songs he wrote in the Pacific Northwest for the Columbia River and Bonneville Dam projects in 1941, and for which he was 25 years later honored by the Department of the Interior. The album cover for those songs—the original masters for which were discovered years later by a government employee and released by Rounder Records—shows Woody with his guitar walking in the foreground, with rivers cascading and mountains rising majestically in the background. It’s a beautiful painting, but quite misleading in that it suggests he wrote Roll On, Columbia and The Great Grand Coulee Dam by walking around outdoors and soaking up inspiration like Wordsworth and Coleridge walking in the Lake District. Woody went up there all right, but he barely saw the fabled objects of his songs; unlike Walt Whitman he did not “loaf and invite his soul.” Woody was working for Uncle Sam, being paid good government money to write songs for one month, and he went right to work—at the local library, to soak up not inspiration, but information. Imagine putting that on the album cover: Woody Guthrie buried in the stacks, surrounded by books and newspapers, furiously taking notes.

With so much symbolism hovering around him, is it still possible to just review an album? I’m not sure, but I will try. As a way in, it may be useful to demythologize Mr. Guthrie just a tad, to try and recover the man who actually wrote some of these songs, before he became a legend. Take for example the great sequence of songs he wrote in the Pacific Northwest for the Columbia River and Bonneville Dam projects in 1941, and for which he was 25 years later honored by the Department of the Interior. The album cover for those songs—the original masters for which were discovered years later by a government employee and released by Rounder Records—shows Woody with his guitar walking in the foreground, with rivers cascading and mountains rising majestically in the background. It’s a beautiful painting, but quite misleading in that it suggests he wrote Roll On, Columbia and The Great Grand Coulee Dam by walking around outdoors and soaking up inspiration like Wordsworth and Coleridge walking in the Lake District. Woody went up there all right, but he barely saw the fabled objects of his songs; unlike Walt Whitman he did not “loaf and invite his soul.” Woody was working for Uncle Sam, being paid good government money to write songs for one month, and he went right to work—at the local library, to soak up not inspiration, but information. Imagine putting that on the album cover: Woody Guthrie buried in the stacks, surrounded by books and newspapers, furiously taking notes.

Woody wrote a song a day for 28 days, proud of his work habits and able to distill mountains of information into such verses as the following:

Uncle Sam took up the challenge in the year of ‘33

For the farmer and the factory and all of you and me

He said roll along Columbia you can ramble to the sea

But river while you’re rambling you can do some work for me.

It was a year’s worth of work for most songwriters, but for Woody it only took one month. That to me is more romantic than all the bucolic scenes of nature one associates with his imagery: a hardworking craftsman turning the straw of knowledge into the spun gold of his best songs.

Woody went to Brooklyn State College adult school for a time; he took classes, he read books, he was a voracious reader—these are the details that have been carefully pruned from his legacy, to create the romantic image of a curly-headed man with a guitar who just woke up in the morning and found a song on his lips placed there by God. It’s a lie, a bold-faced lie, and it has been assiduously inculcated by those who want to believe that songwriting is a gift available only to geniuses, that poets are born and not made, and that all you have to do to write a song is pick up a guitar and start strumming. Woody’s songs did not come out of an empty sound-hole, they came out of a head full of knowledge and ideas and information that he worked hard to improve upon. Woody Guthrie, put this in your pocket and don’t forget it, was above all a learned man. That is what distinguishes his work from a legion of imitators and ignorant singer-songwriters who think that all songs are created equal. Memo to Thomas Jefferson: they aren’t.

My Dusty Road is a testament to an artist who never much cared about expressing his feelings; what he cared about was to tell a good story, to communicate an idea, to document a time and place and event with all the detail he could pack into 17 verses, as he did with The Ballad of Tom Joad, eliciting a mock-angry letter from John Steinbeck, who told him, “F—k you; you told the story of the Joad family in one song that took me 250 pages to write.”

But what makes this collection so extraordinary, as Arlo Guthrie told a recent audience at The Grammy Museum, is its sound quality, often making available for the first time the actual keys that Woody sang in. The original metal masters surfaced about five years ago, originally recorded in the early 1940s by Moses Asch of Folkways Records and financed by Herbert Harris of Stinson Records, a much less famous but remarkable company that released some of the best anthologies of American folk music during its golden age. I have many of their “Folksay” collections, which brought together Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston, Leadbelly, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee, and my first guitar teacher, Ernie Lieberman, who later performed and recorded with the Gateway Singers. Pete Seeger’s performance of Cumberland Mountain Bear Chase on one of their records is what made me fall in love with the five-string banjo; Woody Guthrie’s performance of Hard Traveling was my introduction to playing guitar and harmonica on the same song, twenty years before Bob Dylan brought it to a new generation of folk revivalists. And Sonny Terry’s mouth harp virtuosity on Lost John, where his harmonica becomes a second very human voice has yet to be equaled. Stinson Records had a haloed reputation on my shelf of essential recordings.

And now Rounder Records has released their buried treasures of 54 extraordinary performances by Guthrie in his prime, ten years before his hand coordination and vocal timbre was ravaged by the onset of Huntington’s Disease; it’s like finding the lost library of Alexandria and making it public once again. To me, it’s like unearthing the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Included in this wonderful collection is a 64-page book of rare photographs of Guthrie and his musical friends and lucid, authoritative accounts of the circumstances of each song, including authors of obscure songs that Woody picked up along the way which have not been properly attributed until now, including A Picture From Life’s Other Side, recorded by Woody, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Hank Williams’ alter ego, Luke the Drifter, but written by Charles E. Baer. It’s wonderful when songwriters get the credit they deserve and are so often denied. Woody wrote a thousand songs, but not this one.

Rounder has truly performed a public service, bringing America’s greatest folk singer the scholarship he deserves. The liner notes are by Prof. Ed Cray and Rounder’s co-founder Bill Nowlin.

Finally, to make the packaging a work of art nearly equal to the musical art it contains, there is a replication of Woody’s business card, on which he wrote, “Woody, the Dustiest of the Dust Bowlers,” a note-card guaranteeing Woody $15 for a booking for People’s Artists and a beautiful, loving postcard to his wife, Marjorie Mazia Guthrie, carried in a model suitcase of the kind Woody himself would have had as he went walking that ribbon of highway, above him that endless skyway, and below him that golden valley.

This Rounder Records tribute to Woody, My Dusty Road, was made for you and me.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com He will perform his Woody Guthrie Centennial tribute at the Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest and Folk Festival, Sunday, May 20 at 4:30pm on the Railroad Stage. In the next issue of FolkWorks Ross will review the upcoming Smithsonian Folkways Boxed Set of Woody Guthrie; stay tuned.