MERLE HAGGARD: CLOSE ENOUGH TO TOUCH A LEGEND

Merle Haggard: Close Enough to Touch a Legend

Live in Concert at the Canyon Club in Agoura Hills – December 9, 2014

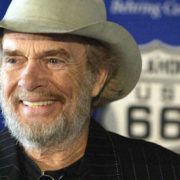

All Merle Haggard had to do was walk on stage last night at the Canyon Club in Agoura Hills and the audience was in the palm of his weather-beaten hands. He squinted out into the footlights (subject of a song he recorded with the late George Jones, We’ll Kick the Footlights Out) and tipped his dark brown Fedora and the audience roared its approval in anticipation of a great concert. He hadn’t even picked up his guitar.

All Merle Haggard had to do was walk on stage last night at the Canyon Club in Agoura Hills and the audience was in the palm of his weather-beaten hands. He squinted out into the footlights (subject of a song he recorded with the late George Jones, We’ll Kick the Footlights Out) and tipped his dark brown Fedora and the audience roared its approval in anticipation of a great concert. He hadn’t even picked up his guitar.

A great concert it was, but that doesn’t begin to describe it: From San Quentin to the Kennedy Center, where the 77-year-old country music legend was honored 4 years ago, the man his friends call simply Hag has come to embody the core American values his fans came to embrace: hard work, hard times, hard time and hard drinking—all surrounded by a soft heart and animated by a keen eye.

The man is brilliant—that’s not in his resume; he has a great sense of humor that had the audience rolling in the aisles (or between the tables last night at this down-home country roadhouse dinner theatre)—that’s not in his resume; he is a great band leader—for whom a nod and a wink communicates as much as what Leonard Bernstein needed to wave both hands in the air to accomplish—that’s not in his resume; and he has a great band—The Strangers—who have been with him since 1965—a fifty-year run that rivals the Rolling Stones for continuity and durability in a world where Program Subject to Change Without Notice is the law of the land.

What Jill and I saw at the Canyon Club last night—from the front row courtesy of Luanne Nast, their Marketing Director who gave me one of the best birthday gifts I have ever received, the best seats in the house at the best concert of the year—was pure magic, a rocking roller coaster ride through the greatest song catalog this side of Bob Dylan—with a few side trips to visit his own dead heroes, such as Johnny Cash (Folsom Prison Blues) and Townes Van Zandt (Pancho and Lefty, which he recorded with Willie Nelson and which I had in fact requested as a birthday gift in my recent FolkWorks concert preview For Merle Haggard On My Birthday; I felt like he was singing it for me.)

But we saw more than a great artist and concert last night—for the Canyon Club is like no other concert venue we have been to. I had imagined some kind of refined hotel atmosphere, with dinner tables in the front and auditorium seating from the middle on back for those who just want to come for the show. That’s not the way it is, folks; it’s turtles all the way down—long dining tables and short from the stage all the way back in this cavernous barn of a concert hall—no refinement at all—just the kind of real down-home roadhouse you might stumble onto out on Route 66; noisy, crowded, and jammed full with huddled masses all there for one reason—to cross the Atlantic of their blues-drenched souls towards the Promised Land—of rural American values where songs are the staff of life—not mere pop entertainment to make you forget your troubles—but music that reminds you where you came from and how hard it was to get here.

If you don’t like people—not just The People as a leftwing symbol—but real live human beings you’ll be sitting right next to and chowing down on real honest American food—steak—Filet Mignon and Porterhouse and New York Cut (but we had the Thai Barbecue Glazed Salmon and there was actually a Vegetarian alternative discreetly hidden in the fine print) then stay away from the Canyon Club, because you’ll feel like you’re in steerage. But the wondrous thing is, by the end of the evening you’ll have made a couple of new friends, as we did just swapping yarns about who our favorite country singer was (Merle, of course) and how many times we had seen him (this was our first time, but across the table we were regaled with stories about visiting Nashville and Memphis and yes, Branson, Missouri to see him—the latter of which Merle described as “proof that God has a sense of humor.”)

Merle Haggard is the closest thing we have to Woody Guthrie and his fictional counterpart Tom Joad—put out on the road in 1935 to escape the Oklahoma Dust Bowl—for whom California was the same Promised Land that Long Island Sound’s Statue of Liberty was to Eastern Europe’s refugees of the late 19th Century. Like Woody, like Tom and Ma and Pa Joad, Merle Haggard is “proud to be an Okie—from Muskogee;”—his huge crowd-pleasing final song.

And yet Merle—his band’s fabled name to the contrary—is no stranger to flouting the law he purports to uphold; after all, unlike all the other so-called country music “Outlaws,” he did hard time and lived to tell the tale. Inspired by a prison concert by Johnny Cash at San Quentin in the late 1950s, Merle Haggard resolved to turn his life around and make something of his G-d-given musical gift. To this day he pays tribute to the Man in Black, his personal savior JC—Johnny Cash before Jesus Christ—by singing his signature song Folsom Prison Blues early in his show.

And at 77 Merle Haggard is no stranger to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune—by which I mean old age. He survived lung cancer and was (mis)diagnosed with a heart condition he was told would require open heart surgery. For a year he assumed he was near death and it informs his rapier quick wit that challenges his close encounter with the grim reaper. He tells the audience that his band “travels with nurses instead of roadies, and an ambulance behind us at all times.” When the audience doesn’t shout and cheer loud enough to suit him after the first provocative line of Okie From Muskogie “We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee” Merle tells us, “Take out your hearing aids and come back to the party—it ain’t over yet!” When someone in the sold-out crowd keeps shouting out, “We still love you, Merle!” he hollers back, “I still love you too!” And then, without missing a beat he deadpans, “It’s just as much fun as it used to be, but it doesn’t take as long,” as the knowing laughter of a lot of fellow senior citizens fills the hall.

But don’t get the wrong idea: Haggard’s indomitable music has crossed generations many times over, and there were young and old alike mixed indiscriminately throughout the hall. Merle’s music is timeless and the old folks there brought their children and they brought their children; his songs are a lasting legacy that will be sung and loved as long as we have an America to sing about.

Herewith some highlights from my annotated set list:

#1) Big City Blues—the perfect opening number to establish his rural roots and permanent American ideal—and to reveal the complicated truth of his life—“Big city turn me loose and set me free,” that it is the tension between the two that energizes his songwriting—not just a paean to a rural past; just as it is the tension between the San Francisco hippies and the Oklahoma mid-American family values that inspired him to write Okie From Muskogee—and now that he has acknowledged smoking pot himself he introduces his 1967 classic with the description “Here’s a song about marijuana,” knowing it will get a thunderous ovation. He could have said, “Here’s a song about waving the flag,” but he doesn’t, because it wouldn’t. Conflict creates drama, and drama is at the core of all great art. As Walt Whitman said, “I contradict myself, very well I contradict myself; I am large, I contain multitudes.” That personal insight comes closer to describing Merle Haggard’s genius than simple homilies to rural Americana. And that is why Hag’s classic song has been embraced by both sides of the American ‘60s generational and cultural divide—because he reaches across it to finally embrace both.

#2) Twinkle, Twinkle Lucky Star shines for reasons having more to do with Haggard’s music than his lyrics; it is the first of several songs that feature a totally un-country tenor saxophone solo by one of the seven Strangers—Renato Caranto—and makes one realize how rich a brew Hag’s music is, mixing country, jazz, folk, blues and rock into a seamless whole that oscillates back and forth across the entire spectrum of American popular music. Three chords and the truth? That’s not Merle Haggard’s idea of country music, and never was—not since he mastered the fiddle-playing Texas Swing of Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys and went on from there.

#3) Folsom Prison Blues—while Merle is not the lead guitarist in the band—he leaves that risky chore to his youngest son Ben—it’s Merle who recreates Luther Perkin’s signature Tennessee Two instrumental introduction to Cash’s prison masterpiece—da da DA DA DA da da—an ascending and then descending slide intro every bit as recognizable as that of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony—which brings the audience along from the first seven notes and defined his rockabilly sound from Sun Records on. “All you can write is what you see,” wrote Woody Guthrie, and while Merle didn’t’ write it, he sings it as if he did—for he did see the inside of those prison walls.

#4) Silver Wings—one of Merle’s most beautiful songs; we heard it over the loudspeakers during dinner, and then were thrilled when we got to hear it live all over again; his singing is understated, almost conversational, and draws you into his magic rather than overwhelming you with it.

#5) Ramblin’ Fever (the other side of song # 16: Sing Me Back Home Before I Die— both songs address that same inner conflict of not being comfortable in one place—whether it’s on the road or in the comforts of home. Sing Me Back Home is Merle’s great prison song—telling the story of a death row inmate as he faces the last lonely mile before the end. It is haunting, unsettling and uplifting all at the same time—a true masterpiece.

#7) I Think I’ll Just Stay Here And Drink— which along with its counterstatement #14: Tonight The Bottle Let Me Down once again explore both sides of his complex relation to alcohol—the latter of which he introduced by saying, “This is for all the drunks in the room,” and then pausing for maximum dramatic effect, “And I see that’s all of us.” As someone about to celebrate my second year of sobriety I felt both songs keenly, and couldn’t help but admire how Haggard could take his lowest points in life and raise them to the level of art by his ruthless personal honesty. That is the hallmark of all great art, as none other than H.D. Thoreau observed. Hag tells the truth—no matter how bad it makes him look, and that is why he is a great artist.

And he finds utterly original ways to encapsulate the truth, as in his great troubled love song, #8) This Cold War With You, taking a motif from modern history and bringing all the way down to an excruciating portrait of a failed marriage—of which Merle had four, before finding a more durable happiness with his fifth; Merle and Theresa just celebrated their sweet 16th anniversary.

He followed that with a modern rock and roll counter-cultural tribute to Woodstock’s Canned Heat, #12) Going Up the Country—evoking the very world he playfully disparages eight songs later with his grand finale #20: Okie From Muskogee. Once again, Merle Haggard proves that America is larger than the red and blue state platitudes so many now want to reduce us to; Hag has one foot in both worlds and that is what sets him apart from the typical Nashville singer who thinks the world begins and ends on Music Row. Hag just rolls from one song to the next without pause—they need no introduction.

But his band did, and the funniest highlight of the show was Merle saying “Let me introduce the band,” and then watching all the members suddenly walk up to each other and introduce themselves as if at a party meeting for the first time; they shook hands across the entire stage in a choreographed bit that had the audience roiling with laughter. Two songs later, with pride and affection, Merle introduced them for real: Their music director is Norman Hamlet on steel guitar; Floyd Domino—with a smile as big as his Stetson cowboy hat—on keyboards; Renato Caranto on tenor sax; Merle’s youngest son Ben Haggard on lead guitar; Taras Prodaniuk on bass guitar; Jim Christie on drums; and Scotty Jost on fiddle, mandolin, acoustic guitar and backing vocals.

Perhaps the most surprising departure from what I had mistakenly imagined to be the kind of song Merle Haggard would sing was #17) the 1930 Sleepy John Estes classic Milk Cow Blues, which has since wound its way through the repertoires of everyone from Elvis to Willie Nelson, and on which he brought the roadhouse down with his Fender Telecaster’s bluesiest licks. Yet again this American master crosses over every kind of cultural divide—this time between black and white and demonstrates without rancor that we are one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice and Haggard for all.

What a gift to be given on one’s 68th birthday—by both Merle Haggard and the Canyon Club’s Marketing Director Luanne Nast, who put Jill and me right in front of the stage, where we were close enough to reach out and touch a legend. Thank you, Luanne!

On Wednesday, December 24 from 5:00 to 9:01pm at the Friends Meeting House at 1440 Harvard St in Santa Monica Ross Altman will host a musical and spoken word commemoration on the Centennial of the Christmas Truce December 24 1914 when troops on both sides of No Man’s Land in Europe spontaneously laid down their arms. Soldiers from Germany, England and France all sang Silent Night and other Christmas carols, swapped cigarettes and chocolates and played football. It was a bright moment during a dark time, when John Lennon’s imagined better world, however briefly, came true. It is not to be forgotten and on the Centennial will be remembered with songs and stories as timely today as during World War I. Fellow folk musicians Jill Fenimore, Neil Hartman, Carol McArthur, Peter Quentin, and Ellen and Stuart Silverman will join Ross for an evening devoted to memory, peace and after a 7:00pm break for refreshments (potluck) a holiday sing-along . $5 suggested donation; no one turned away.

Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com