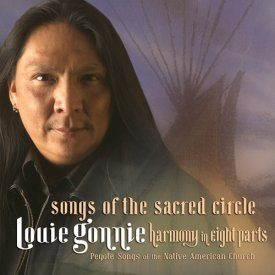

LOUIE GONNIE – SONGS OF THE SACRED CIRCLE

ARTIST: Louie Gonnie

TITLE: Songs Of The Sacred Circle

LABEL: Canyon Records

Driving up Angeles Crest Highway en route to the Haramoknga American Cultural Center, I popped Louie Gonnie‘s Songs of the Sacred Circle: Harmony in Eight Parts into my CD player. It seemed fitting to listen for the first time to his collection of peyote songs just before attending a performance of Native American flute players, part of the World Festival of Sacred Music. The fast-paced of shaking of a high-pitched gourd rattle opened the first song, Dreamscapes. I gazed dreamily at the craggy San Gabriel Mountains and blue sky while Louie Gonnie sang in his native Dine language, his heartfelt voice moving up and down within a small range of intervals. As I rounded the bends of the mounting highway, the music harmonized with the natural landscape.

Then I remembered I was expected to review this CD.

Facing the blank page the next day, I was wracked by qualms and questions such as: How does one review sacred music? Is that even appropriate? Does sacred music fall under the same aesthetic scrutiny as music we listen to for pleasure? Should we rather – or also – evaluate it with regard to the purpose for which it was composed such as enhancing meditation, healing, inspiration or atonement? When this sacred music comes from a tradition different from Western music, what means do we use to analyze it, let alone evaluate it?

Consider an example from the Western liturgical tradition. Bach’s Mass in B Minor is often performed in concert halls, yet it was intended to accompany a sacred ceremony. Reviewers today seem to have no problem commenting on the cohesiveness of the orchestra or the strength and purity of the soloist’s voices.

The Mass, in fact, provides an excellent parallel to the Peyote Ceremony which spurred Louie Gonnie to compose Songs of the Sacred Circle. According to Catholic belief, wafers and wine are transformed into the body and blood of the deity. The musical mass follows a specific order to accompany the ceremony. So, too, in the Native American Church, music accompanies the Peyote Ceremony in which a plant with powerful transformational properties is consumed by believers.

Before commenting on the latest songs Louie Gonnie has composed for the Peyote Ceremony, I want to briefly examine the historical and cultural context for peyote songs. The small spineless cactus known as peyote (Aztec “peyotl”) grows in north central Mexico and Texas. Scholars date the deification of the plant by indigenous tribes of North America to earlier than 5,000 years B.C. The Carrizo tribe of northern Mexico is thought to have instructed tribes from nearby areas in the ceremony, which included all-night dancing around a fire. Thus the Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, and Comanche spread the Peyote Ceremony across the Southwest and into Plains.

Sacramental use of the cactus was documented during the period of Spanish invasion and colonization of the 16th century. By 1620 the Spanish Inquisition had pronounced it diabolical and made its use illegal. The transmission of the ceremony some 500 miles to the north of its origins is confirmed in a 1630 Inquisition report from Santa Fe, New Mexico denouncing its use in divination by Native Americans in the area.

In the 19th century, peyote took on a new importance in the survival of Native Americans after successive defeats by the United States army. The agonizing disintegration of Native American culture and traumatic resettlement and confinement in reservations led many Oklahoma-based tribes to use the cactus as a remedy to relieve mental suffering and inspire vestiges of hope. But now, Native American peyote users had to contend with the disapproval of Christian missionaries. How the ceremonial use of peyote evolved into the Native American Church is a long, complex, and not completely clear story. However, it is known that two major figures took different routes to establishing Peyote meetings as an intertribal institution and a foundation for the Native American Church. Albert Hensley, a Winnebago educated at an Indian school and influenced by missionaries, regarded peyote as both a Holy Medicine and a Christian sacrament. He integrated elements of Christianity into his branch of the NAC. Quanah Parker, a Comanche, promoted the “Half Moon style” peyote meetings, which remained freer of Christian influence. Towards the end of the 19th century, Native American tribes began lobbying for religious freedom to use peyote sacramentally, a movement that was ultimately supported by Congress. Today, chapters of the Native American Church of North American exist in every state west of the Mississippi.

A major part of NAC ritual consists of singing accompanied by a gourd rattle and small, rapidly-pounded drum. Prayer and meditation also make up the ritual, which centers on consumption of the Holy Medicine. Peyote is reverently passed around the circle of church members throughout the night. Meetings are held for healing, baptism, funerals, and birthdays.

The issue of recording peyote songs has been controversial within the Native American Church. Louie Gonnie learned the traditional peyote songs from his grandfather, medicine man Haastin Gonnie. Since 2000, he has been composing original peyote songs, many of which he recorded informally on tapes which he shared in his personal circle. After he released two collections of his songs, Sacred Mountains (2005) and Elements (2007), the positive reception in Indian and non-Indian communities made his music into a marketable commodity. Some of his tapes from several years ago fell into greedy hands. Bootleg copies were sold at Indian gatherings. Gonnie has told interviewers that he had not, in fact, intended to release these songs for some years, but with bootleg copies already in distribution, he responded with the Canyon Records-produced Songs of the Sacred Circle: Harmony in Eight Parts, a collection of 32 songs dating back to 2000.

Gonnie has taken the sacred songs to a level of sound complexity not found on the bootleg copies, tastefully multi-tracking to add depth to his vocals. Without translations of the Dine text, we cannot know how the music underscores the spiritual message in specific terms. Yet one feels an underlying serenity in the series of songs with their subtly varied moods. Inexplicably, one feels uplifted.

I don’t pretend to have answered the questions about reviewing that this CD raised for me. I don’t know if we should even call the above paragraphs a review. But I will tell you that I especially recommend listening to Songs of the Sacred Circle: Harmony in Eight Parts while driving in the mountains.

Audrey Coleman is a writer, educator, and passionate explorer of world music and culture.