LEAD BELLY: KING OF THE 12-STRING GUITAR

ARTIST: LEAD BELLY

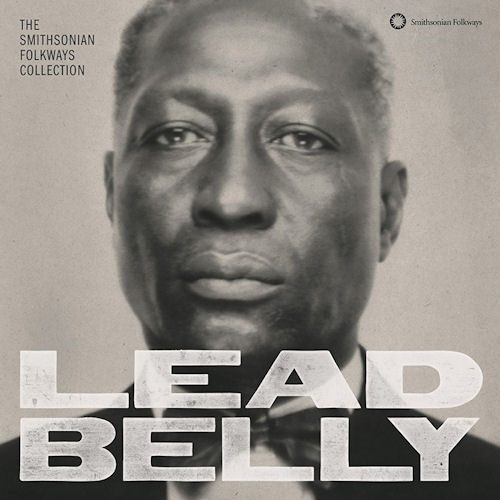

TITLE: LEAD BELLY: THE SMITHSONIAN FOLKWAYS COLLECTION

LABEL: SMITHSONIAN FOLKWAYS

PRODUCED BY: JEFF PLACE AND ROBERT SANTELLI

RELEASE DATE: FEBRUARY 24, 2015

LEAD BELLY: KING OF THE 12-STRING GUITAR

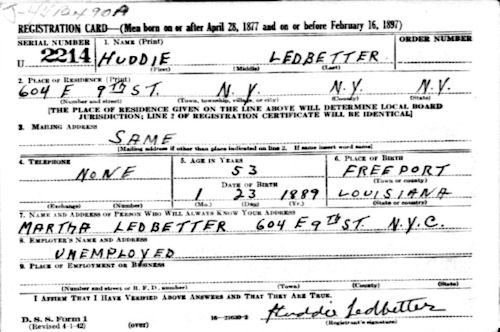

How did Leadbelly spell his name? In the Oak Publication The Leadbelly Songbook there is a photo of a handwritten note written by Leadbelly in which he signs his name at the bottom. Guess what; he spells it as one word—Leadbelly. That’s the way almost all the original Folkways releases spelled it too—and the Folkways tribute album A Vision Shared: the Songs and Legend of Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly. So why is this new and by all accounts definitive box set of Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection suddenly revising his own spelling?

How did Leadbelly spell his name? In the Oak Publication The Leadbelly Songbook there is a photo of a handwritten note written by Leadbelly in which he signs his name at the bottom. Guess what; he spells it as one word—Leadbelly. That’s the way almost all the original Folkways releases spelled it too—and the Folkways tribute album A Vision Shared: the Songs and Legend of Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly. So why is this new and by all accounts definitive box set of Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection suddenly revising his own spelling?

Political correctness, pure and simple; they must think his name looks more respectable spelled as if it were two words. But as Woody Guthrie reminds us, Lead wasn’t his first name, and Belly wasn’t his last name. That was Huddie Ledbetter. And as everyone who knew him knows, Leadbelly was anything but respectable.

From his name all the way down to his steel thumb pick, Leadbelly was heavy metal. “The hard name of a harder man,” wrote Woody Guthrie in his groundbreaking essay “The Singing Crickett and Huddie Ledbetter,” in which he single-handedly swept away his own formidable reputation and declared Leadbelly to be America’s greatest folk singer. From the Dust Bowl Balladeer those were words to reckon with. Smithsonian Folkways—with their new magnificent boxed set of the same proportions as their 2012 definitive Centennial edition of the Smithsonian Folkways Woody Guthrie Boxed Set our nation’s single greatest repository of recorded sound has at last put them up on the same narrow shelf—side by side—where they belong. This is the Harvard Classics of folk music—the beginnings of the Great Books. This is the American Treasury of folk, and it includes 16 previously unreleased tracks; call them Leadbelly’s Lost Sessions, such as his topical songs about the Scottsboro Boys, the Queen Mary, the marriage of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, The Hindenburg Disaster and his World War II masterpiece, We’re Gonna Tear Hitler Down.

From his name all the way down to his steel thumb pick, Leadbelly was heavy metal. “The hard name of a harder man,” wrote Woody Guthrie in his groundbreaking essay “The Singing Crickett and Huddie Ledbetter,” in which he single-handedly swept away his own formidable reputation and declared Leadbelly to be America’s greatest folk singer. From the Dust Bowl Balladeer those were words to reckon with. Smithsonian Folkways—with their new magnificent boxed set of the same proportions as their 2012 definitive Centennial edition of the Smithsonian Folkways Woody Guthrie Boxed Set our nation’s single greatest repository of recorded sound has at last put them up on the same narrow shelf—side by side—where they belong. This is the Harvard Classics of folk music—the beginnings of the Great Books. This is the American Treasury of folk, and it includes 16 previously unreleased tracks; call them Leadbelly’s Lost Sessions, such as his topical songs about the Scottsboro Boys, the Queen Mary, the marriage of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, The Hindenburg Disaster and his World War II masterpiece, We’re Gonna Tear Hitler Down.

And it was a long time coming. Lead Belly made his Library of Congress recordings in 1937, the same year he wrote Bourgeois Blues, my candidate for the hardest-hitting protest song of the 20th Century. His was the first album on Moe Asch’s Folkways Records; indeed he was the reason Asch created Folkways: Negro Folk Songs for Children, a brilliant stroke of marketing genius, because Moe knew he had to do something to soften Lead Belly’s reputation as a convicted murderer and ex-convict. What better way than to emphasize Lead Belly’s ability to entertain kids? There was nothing phony about that, however, as there are magical live recordings of Lead Belly’s children’s concerts that demonstrate his delightful way with this audience—long before Pete Seeger had refined it to a modern art form.

Indeed, like so many of his fans, that is when I was introduced to his music. I was about six years old when my mother first put on a Lead Belly record, and after listening to the sweet, mellifluous trained voices of Burl Ives and Richard Dyer-Bennett I was frankly put off by the sheer raw power of Huddie Ledbetter. My ears weren’t ready for him. But my mother—to her everlasting credit—didn’t give away her Lead Belly records just because I found them harsh. Ten years later—there they still were, and after having found my way to Bob Dylan’s nasal blues vocal timbre and appreciated his truth telling I was ready for the original source of those early ‘60s white blues singers—Lead Belly. I was amazed at how much his voice had improved in the intervening ten years. The untrained voice that had grated on me as a six-year old went straight to my heart and never let go.

My email address, greygoosemusic@aol.com is taken from one of these children’s songs—which is also the name of my music publishing and record company, and thus my homage to Lead Belly—about an indestructible Grey Goose.

The knife couldn’t cut him, Lord, Lord, Lord,

And the fork couldn’t stick him, Lord, Lord, Lord

The hogs wouldn’t eat him, Lord, Lord, Lord,

And the last time I seen him, Lord, Lord, Lord

He was flying o’er the ocean, Lord, Lord, Lord

With a long string of goslings, Lord, Lord, Lord

They all went quack quack, Lord, Lord, Lord.

Lead Belly’s fabulous goose—a symbol of survival for black people through all adversity—has been with me throughout my own journey as a folk singer inspired by “The King of the !2-String Guitar.” And yes, my 12-string is tuned down two full steps to Lead Belly tuning—so D is Bb—the key he played Bourgeois Blues and Goodnight Irene.

At sixty-eight he remains my favorite folk singer, just like Woody Guthrie said he was. Once you’ve heard Lead Belly you can listen to Black Sabbath and Metallica all day long and not be taken aback—they all sound tame in comparison. He’s a one-man heavy-metal band, and the voice of his 12-string guitar is more than a match for a full electric band—there is simply nothing in recorded music history quite like it. It’s the perfect guitar for his voice, and may now be seen up close and in person at the Grammy Museum in L.A.

As Woody Guthrie reminded us, however, his first name wasn’t Lead, and his last name wasn’t Belly. He was born Huddie Ledbetter, in 1888, January 15, in Mooringsport, Louisiana—near Shrevesport—which he celebrated in his classic song Fannin Street (Mr. Tom Hughes’ Town). His birth date is approximate due to the fact that no official birth records were kept of black people in the 19th Century. He got the name Lead Belly not from some publicist trying to jack up his reputation and record sales; nor from some journalist in a rock club trying to create a hook and a headline; he got it from his fellow prisoners on a Texas chain gang in Sugarland, the name of the town and prison that he put in the first song John Lomax recorded him singing—The Midnight Special:

If you ever go to Houston

Boy you better walk right

You better not swagger

You better not fight

Sheriff Benson will arrest you

Paine and Boone will take you down

You say anything about it

You’re Sugarland bound.

It also happens to be disgraced Congressman Tom DeLay’s home town—and the prison he was assigned to when he was convicted of malfeasance:

Let the Midnight Special

Shine her light on me

Let the Midnight Special

Shine her ever-loving light on me.

70 years after Lead Belly sang it for the man he always called “Mr. Lomax,” prisoners are still singing this iron man’s song. That’s staying power.

The Lead Belly Special Exhibit is currently on display on the second floor of the Grammy Museum, with artifacts from his entire career, including one of the legendary pardons he received from two governors—Pat Neff in Texas and OK Allen in his home state of Louisiana. Legend has it that he sang his way out of prison, composing a song he sang for both governors:

If I had you, Governor Neff, like you got me

I’d wake up in the morning and I’d set you free.

You can see the most important guitar of the 20th Century—Lead Belly’s specially made Stella—designed with extra heavy bracing to support his extra heavy strings. It’s the guitar that Lead Belly’s niece Tiny Robinson tried to auction off for $300,000 some years back so it would have become the most expensive guitar in history—surpassing Jimi Hendrix’s Woodstock Fender Stratocaster that played The Star-Spangled Banner and sold for $270,000 at auction.

Fortunately, Robinson’s minimum asking price was never met and the guitar remained in her family’s hands. It is currently on loan from the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland and this may be your only chance to see it. Grammy Museum vice-president Robert Santelli—who wrote the introduction to this majestic book, which was written by Smithsonian Folkways archivist and the album’s co-producer Jeff Place—was the curator of this exhibit, which he originally curated for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s grand opening. It is therefore a wonderful opportunity to see something you would previously have had to go to Cleveland to see.

Think of it as visiting a National Monument, for if you believe in the power of folk music to change our lives and bring transcendent beauty to our quotidian existence that is no exaggeration. To me it was tantamount to visiting the Grand Canyon or Yosemite or the Lincoln Memorial. To look at it is to hear the Rock Island Line, the Midnight Special, the Bourgeois Blues and Goodnight Irene—Life Magazine’s choice for the Song of the Half Century in 1950, when the Weavers hit recording—just six months after Lead Belly died on December 6, 1949, stayed on top of the Hit Parade for 13 consecutive weeks, longer than any song in history until a quarter century later in 1975, when the Bee Gees Saturday Night Fever finally broke the record. The date of his death, by the way, is not approximate, since by that time Lead Belly was world famous and it was reported on the front page of the New York Times.

Think of that: Not the Beatles, the Stones, Frank Sinatra or Elvis ever had a hit song that lasted longer at Number 1 than the Weavers recording of Goodnight Irene—and it was Lead Belly’s theme song that put them there. Wow! That should in and of itself give the lie to anyone who thinks folk music is just a quaint pastime for old-timers and the musical equivalent of an antique store. Folk music was right at the center of the musical explosion of the 1960s—its cornerstone and foundation. The Weavers, Peter, Paul and Mary, the Kingston Trio, Erik Darling’s Rooftop Singers, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez—they all stood on Lead Belly’s broad shoulders.

This Smithsonian Folkways Collection of five CDs of Lead Belly’s music represents a supremely generous sampling of the Folkways archives released on more than a dozen LPs and 10-inch Long-Playing records—(of 55 album covers in total displayed in a group photograph near the end of the book) for the first time gathered together in one set and annotated with a handsome, majestic book of photographs and essays that touch on all the vicissitudes of Lead Belly’s storied life—two prison terms (20 years behind bars in all), chain gang leader, something of a plantation-era relationship with the white folklorist who discovered him—John Lomax—and a series of romantic relationships that swirled around his rock of a wife—whom he married early on and never abandoned, Martha Promise, ending with his tragic death at 60 from Lou Gehrig’s Disease. As said above, Woody Guthrie called him the greatest folk singer of all, and only Woody was in a position to make that call. With the publication of this magisterial book—with detailed annotations of all the songs by author Jeff Place—Place has put his stamp on Folkways Records as much as its founder.

Despite Moe Asch’s prescient introduction of Lead Belly to the public through his children’s songs, his life is by no means a children’s story, and the wide range of his songs weaves Lead Belly’s music into his involvement with passionate women who were drawn to his volcanic and at times violent nature. He carried either a knife or gun with him for protection at all times, and was not reluctant to use it. In his spoken intro to Silver City Bound he makes passing reference to this part of his life in a tribute to Blind Lemon Jefferson, for whom Lead Belly was his guide; “He was a blind man, and I used to lead him around. We set down in the train station and start playing for the women; cause that would bring the men and they would bring the money; we’d have those women falling all over us.” Songs such as Big Fat Woman, Yellow Gal, Black Girl, and Keep Your Hands Off Her, evoke these relationships—which even inspired a book of poems—Leadbelly: A Life in Poems (2004), by the young African-American poet Tyehimba Jess.

The leftwing New York folk singers who gathered around him in his later years apparently never saw this probably long-since discarded side of him, and regarded him as an extension of the way he dressed—a distinguished gentleman, with a pin-striped suit and bow-tie at all times he appeared in public. Lead Belly was the antithesis of the Woody Guthrie styled working class folk singer—after whom Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan and most other well-known performers modeled themselves. One exception who stood out for that very reason was protest singer Phil Ochs.

Perhaps Lead Belly wanted to distance himself as far as possible from the convict’s uniform he wore so many of his early years locked up in Sugarland, Texas and Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana, where in 1934 he met John Lomax, who had come there with his son Alan looking to collect Negro folk songs. When he found Lead Belly he struck gold—the richest repertoire of authentic American folk music in one informant ever discovered.

It was Lead Belly who gave Lomax The Midnight Special, a prison song and a train song derived from an Underground Railroad song, Let It Shine On Me, which Lead Belly also sang. When Lomax cranked up his heavy direct to acetate recording machine that was the first song Lead Belly sang for him:

Yonder comes Miss Rosie

How in the world do you know

I can tell her by her apron

And the dress she wore.

Umbrella on her shoulder

Piece of paper in her hand

She goes a-marching to the captain,

Say’s, “I want my man.”

Let the midnight special shine her light on me.

Let the midnight special, shine her ever loving light on me.

Copyright 1936 Folkways Music Publishers, Inc., New York, NY.

This signature song is often described as a prison song, but like its predecessor it is also a freedom song. In both light is used as a symbol of freedom. In the Midnight Special it refers to the head light on the front of the train, which the prisoners believed was a good omen; if it shined through your cell bars it meant you would get paroled. In the Underground Railroad song the light was just as specific: it referred to the light houses along the southeastern coast that were used as signaling stations on the journey to freedom. Friendly light house keepers would keep the light on to indicate there was sanctuary on the neighboring farm; if the light was turned off it meant the slaves and their “conductor” had to keep traveling. Let It Shine On Me is thus a perfect example of the “coded” songs of the Underground Railroad; slave masters could hear it as a simple spiritual reference to Heaven; escaping slaves could interpret it as a signal of safe haven. A Negro Spiritual and a prison song: they were both freedom songs to Lead Belly.

This signature song is often described as a prison song, but like its predecessor it is also a freedom song. In both light is used as a symbol of freedom. In the Midnight Special it refers to the head light on the front of the train, which the prisoners believed was a good omen; if it shined through your cell bars it meant you would get paroled. In the Underground Railroad song the light was just as specific: it referred to the light houses along the southeastern coast that were used as signaling stations on the journey to freedom. Friendly light house keepers would keep the light on to indicate there was sanctuary on the neighboring farm; if the light was turned off it meant the slaves and their “conductor” had to keep traveling. Let It Shine On Me is thus a perfect example of the “coded” songs of the Underground Railroad; slave masters could hear it as a simple spiritual reference to Heaven; escaping slaves could interpret it as a signal of safe haven. A Negro Spiritual and a prison song: they were both freedom songs to Lead Belly.

And it was Lead Belly who gave Lomax Goodnight Irene, which he learned in 1912 from his uncle Terrell, and which shortly after Lead Belly died fifteen years later became the Weavers number 1 song in the country for 13 weeks. When Lomax first heard it Lead Belly was wearing prison stripes, a long way from the pin stripe suits he later donned.

It took four men to play him when they made The Midnight Special, the movie based on his life. Michael Cooney pointed this out in a concert I heard him do in Springfield, Illinois, during his great tribute to Lead Belly—on a 12-String guitar Michael played with Lead Belly’s original arrangements—including one of the most complex—Mr. Tom Hughes’s Town. Cooney taught me that the producer of the movie used one actor to play Lead Belly, one great guitarist to play the 12-String, one to sing the parts, and—since the guitarist was white—a fourth actor to just pretend to play the guitar so they could film only his black hands moving up and down the fret board.

The guitarist was Dick Rosmini—whom I had the good fortune to meet at a party in Los Angeles and whose record of 12-String instrumentals I cherish to this day. He is well worth mentioning for another reason: Rosmini died of the same disease that struck down Lead Belly, Lou Gehrig’s disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.

Another wonderful musician Lead Belly influenced was the late Fred Gerlach, who I got to hear in concert and meet in person when performing at the Roots Festival in San Diego. Fred also recorded for Folkways (now Smithsonian Folkways); when he built his first enormous 12-String guitar to recreate the sound of Lead Belly’s Stella the string tension put so much pressure on the bracing and bridge that the guitar exploded in his hands. It was as dangerous to watch Fred Gerlach in his luthier’s studio as it was to observe a chemist working with nitroglycerine. It took several guitars to get the balance right, but the sound he was finally able to produce made it worth the effort. The King of The 12-String Guitar was an elusive muse and standard of perfection to strive for.

Lead Belly continues to influence musicians to this day. Cat Stevens (Yusuf) just released his first album in thirty-five years and the title Tell ‘Em I’m Gone comes from the Lead Belly chain gang song on it: Take This Hammer Unlike Pete Seeger and Lee Hays hit song If I Had a Hammer, this is no metaphoric hammer; it’s as real as John Henry’s: “Take this hammer (wow!)/Carry it to the captain (wow!)/Take this hammer (wow!) /Carry it to the captain (wow!)/Take this hammer (wow!)/Carry it to the captain (wow!) /Tell ‘em I’m gone, (wham!)/Tell ‘em I’m gone.” Lead Belly sang it as a work song, and taught it to Pete Seeger, who demonstrated its use as a chopping song during many concerts—with a long pause for the “wow!” or “wham!” after each line—to accent the hammer or ax coming down.

From Woody Guthrie to Pete Seeger to Cat Stevens; Leadbelly touched us all—and like an alchemist, he transmuted lead into 24-carat gold.

Legend of Lead Belly premiered February 23, 2015 on the Smithsonian Channel. This documentary traces the life, career, and influence of Lead Belly. Watch it now

Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection, the first career-spanning box set dedicated to the American music icon, will be released on February 24, 2015. The 140-page, large-format book includes 5 CDs with 108 tracks (16 previously unreleased), accompanied by historic photos and extensive notes about the musician now celebrating what would have been his 125th year.

Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com

LEAD BELLY: KING OF THE 12-STRING GUITAR

ARTIST: LEAD BELLY

TITLE: LEAD BELLY: THE SMITHSONIAN FOLKWAYS COLLECTION

LABEL: SMITHSONIAN FOLKWAYS

PRODUCED BY: JEFF PLACE AND ROBERT SANTELLI

RELEASE DATE: FEBRUARY 24, 2015

LEAD BELLY: KING OF THE 12-STRING GUITAR