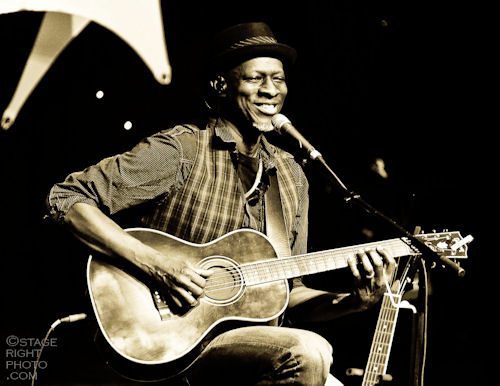

KEB’ MO’ AT GRAMMY MUSEUM

Straight Out of Compton: Keb’ Mo’

An Evening at The Grammy Museum: May 14, 2014

Tall, dark and strikingly handsome, Keb’ Mo’ (born Kevin Roosevelt Moore, October 3, 1951) was born and raised in Los Angeles, a long way from the Mississippi Delta, but he has made the Delta Blues his own as if it was his birthright. If you thought that the best contemporary blues guitarists are old white guys who learned their trade from the likes of Reverend Gary Davis and Mississippi John Hurt—such as the recently reviewed John Hammond, David Bromberg, Stefan Grossman and Roy Book Binder—think again. Keb’ Mo’ is living proof that contemporary black performers have continued the tradition of their great black forebears with every bit as much dedication and bluesmanship as Robert Johnson, Blind Willie McTell, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Big Bill Broonzy.

Tall, dark and strikingly handsome, Keb’ Mo’ (born Kevin Roosevelt Moore, October 3, 1951) was born and raised in Los Angeles, a long way from the Mississippi Delta, but he has made the Delta Blues his own as if it was his birthright. If you thought that the best contemporary blues guitarists are old white guys who learned their trade from the likes of Reverend Gary Davis and Mississippi John Hurt—such as the recently reviewed John Hammond, David Bromberg, Stefan Grossman and Roy Book Binder—think again. Keb’ Mo’ is living proof that contemporary black performers have continued the tradition of their great black forebears with every bit as much dedication and bluesmanship as Robert Johnson, Blind Willie McTell, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Big Bill Broonzy.

The blues is more than skin deep, despite Leadbelly’s observation that “Never was a white man had the blues.” Even though I don’t sing them, I’ve had them. Still, I was happy to hear one of the leading voices of a new generation of black blues performers who have gone back to the roots of acoustic country blues that predates the electric Chicago sound of B.B. King and Muddy Waters, which became more popular in terms of commercial music. It is refreshing to hear and see artists like Guy Davis and Keb’ Mo’ carrying on these older Delta and Piedmont blues traditions in the same spirit that artists like Mike Seeger, John Cohen and Tom Paley carried on the white string band music of the 1920s in the folk revival as The New Lost City Ramblers. “Black and White together,” I say, “We shall not be moved.”

Under a big fat full moon at The Grammy Museum this Wednesday, Keb’ Mo’ enlightened the audience with his own oral history before entertaining us with his own profoundly uplifting blues songs, such as More Than One Way Home and Life Is Beautiful. “The blues ain’t pretty,” one of his mentors had told him, “You play all that pretty shit.” But when you have a beautiful voice, what are you going to do, not use it? Keb’ Mo’ revels in what he calls his “clean approach to the blues,” and is happy to let others carry the torch for grit, gravel and guttural intonations of the blues.

As he said a number of times last night, he wasn’t interested in just copying the greats, he wanted to learn from them and eventually find his own voice. Most revealing in his many anecdotes of mastering the guitar style of “The King of the Delta Blues,” which started him on his way, was his emphasis on analyzing the why of how they played, rather than the how. Instead of simply learning how they played a particular lick at a particular time, Keb’ Mo’ focused on why they played a lick when they did, and once he understood that, he was free to play his own style, building on their examples.

That is why even though he was talking and afterwards playing his own songs in a traditional blues guitar style last night, his music did not sound like a museum piece, but the voicing of an original artist, like a poet who has learned Keats and Shelley before moving on to find their own voice. It was also refreshing to hear an artist who had brought his own neighborhood—the “hood” if you will—of Compton with him, where he was raised and graduated from Compton high school in 1969—all the way to Nashville, where he now lives. I am sure there are not many Nashville songwriters who travelled the road Keb’ Mo’ did to get to his own personal “crossroads,” his on-going tribute to Robert Johnson.

Faced with the need to earn a living Keb’ Mo’ recounted at some length his false starts and failures as he went first to LA Trade Tech in the 1980s and then LA City College in the early 1990s thinking he would become an electrician before reaching the conclusion that he had to put all his eggs into music. Before he could let go of the fear it took to arrive at that existential decision, however, he said in response to Grammy Museum Executive Director Bob Santelli’s probing questions, he had to reconcile himself to “the worst that could happen if he didn’t make it.” And he didn’t mince words: he would have to accept that he could wind up homeless, on skid row, and living in a box. At the time, he said, “My Datsun B-210 was still running, so I could get to my gigs, and I could cook and live on beans and rice.”

That was all he needed, and with that personal knowledge he was able to take Robert Frost’s “Road Not Taken,” and commit himself to music full-time. Fortuitously at just this point in his artistic evolution he was invited to understudy (off-stage) the character of “Guitarman” in Leslie Lee’s play Rabbit Foot, at the Mark Taper Forum. In this off-stage role he played all the guitar music. For the first time he was making a weekly salary of $400, that exceeded the $50 a week he had earned as an electrician. He was on his way.

His eponymous debut album “Keb’ Mo’” came out in 1994, and his second album won his first of three Grammys. Last night after his oral history he regaled the audience with a short set of his own songs—but for one classic that for me was a sound for sore ears. He traded his “Keb’ Mo’” Signature Bluesmaster Gibson guitar—which at least faintly resembles the small-body Gibson one remembers from the only known photograph of Robert Johnson—except that it has a pick-up and fills the sold-out Grammy Museum with its rich shimmering finger-style trebles and alternating bass line that accompanies many of Keb’ Mo’s original songs—for the National Resonator N that sat on the other side of the stage.

With that instrument he added a bottleneck and started playing a well-worn melody on slide guitar; it took a few bars before I suddenly realized I was listening to Katharine Lee Bates and Samuel A. Ward’s America the Beautiful—and Keb’ Mo’s tribute to Ray Charles—the highlight of the show. It took a few bars to realize the tune because it was so unexpected, after the sound of the Mississippi Delta that preceded it. But it was truly gorgeous, and slyly humorous as well, when this modern blues master recounted how in the second verse you would get to hear Ray Charles’ signature lyrical add-on: “Now wait a minute, people; I’m talking ‘bout America, America, God shed his grace on thee…” before admitting that he couldn’t “do it like Ray.” It was humbling and inspiring too.

And with that Keb’ Mo’ graciously stood up and took his bow, and told the audience how grateful he was that “we” had allowed him to make his living playing this music for the past twenty years. By this time the entire Grammy Museum audience was on its feet, giving a richly deserved standing ovation to an artist who is a vital link to an ancient tradition, and living proof that the blues has more than one road to travel—and that—as he put it so well in his own song—“there is more than one way home.”

Keb’ Mo’s new album, his 12th, is called BLUESAmericana—a melding of the sound of the blues with his personal stories of growing up in Compton and finally fulfilling search for a long-lasting marriage in songs like Do It Right and For Better Or Worse. It debuted at #1 on the Billboard Blues Chart and #2 on the Billboard Folk Chart. You didn’t know there was a “Billboard Folk Chart”? Neither did I; just one of the many things I learned from listening to this great American artist, Keb’ Mo’. He is down-to-earth—and still evokes the gospel music depth of his church roots at The Beaulah Baptist Church in Watts—where—even though he never joined the chorus—he learned to sing.

Well, not entirely; his parents could afford to buy but one album, he confided. It was Johnny Mathis’ Greatest Hits. He listened to it until there were no grooves left on the vinyl. So if you want to understand the complexity of Keb’Mo’s musical explorations, keep that in mind: on the one side, Johnny Mathis, on the other, Robert Johnson. They are the bookends of Keb’ Mo’s unique creative life. And by the way, if you wondered, like I did, from where he got his name—it’s not complicated, and he was happy to reveal it, again in response to Grammy Museum Executive Director and author Bob Santelli’s beautifully layered questions: “Oh, that’s just the way colored folks say “Kevin Moore.” He heard it once at a small blues club, where they were shouting for him to play an encore: “Keb’ Mo’! Keb’ Mo’!”

And he suddenly broke out into a Big Wide Grin, the title of his 2001 children’s record, and the source for his blues-inflected arrangement of America the Beautiful. When asked what his aim was as an artist, his heart-felt simplicity hit home for me: “I always go for truth.” Socrates couldn’t have said it any better. We are lucky to have this blues philosopher still walking the streets of Athens, still teaching the children. Keb’ Mo’!

Thanks to Andie Cox at the Grammy Museum for the press pass.

On Sunday, May 18 at 4:30pm on the Railroad Stage of the Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest in Paramount Ranch Ross Altman will present Sing Out for Pete! See www.topangabanjofiddle.org for tickets, information and volunteer opportunities.

On Sunday, May 25 Ross Altman will be honored by the Chinese human rights organization the Visual Artists Guild for his song Tiananmen Square, which he will sing in Chinese. See his May/June column Tiananmen Square for details and reservations.

On Saturday, May 31st 2014 Ross will present a protest song workshop and concert at the Claremont Folk Music Festival at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden. Time: 10AM-9PM. Tickets; General Admission: $40

Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com