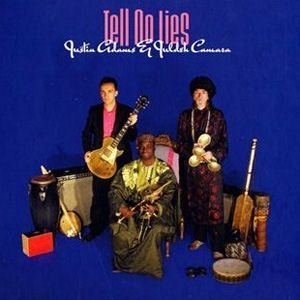

JUSTIN ADAMS & JULDEH CAMARA – TELL NO LIES

ARTIST: JUSTIN ADAMS & JULDEH CAMARA

TITLE: TELL NO LIES

LABEL: REAL WORLD RECORDS

The combination of British guitarist/producer Justin Adams and Gambian spike fiddle (ritti) master, Juldeh Camara, produces a sound that either completes the circle of Africa-to-America and-back-again musical history or, at the very least, takes a part of the arc and intersects it with a new kind of Afro-blues genre.

The combination of British guitarist/producer Justin Adams and Gambian spike fiddle (ritti) master, Juldeh Camara, produces a sound that either completes the circle of Africa-to-America and-back-again musical history or, at the very least, takes a part of the arc and intersects it with a new kind of Afro-blues genre.

On their newest recording, Tell No Lies, the obvious riffs from classic blues tunes weave in and out of many of the songs. Echoes of Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, John Lee Hooker and Slim Harpo resonate throughout, but Camara’s Fulani vocals (a nomadic people of Gambia and other countries across West Africa) and ritti sawing cut deeply through Adams’ thick guitar lead lines. The musical collaboration benefits from some free improvisation as each performer has the ability to take a lick two from the other and then push the songs on a soulful journey via their respective instruments (their last recording is entitled, Soul Science, after all). It’s no coincidence that Camara is of that noted clan of wandering poet/musicians known as the griot. Hence, both his music and lyrics bring the listener into his storytelling circle where he offers the poetry of his observations and a lot of worldly advice. (Note: For the most part, all songs are sung in Camara’s tongue, but a brief synopsis of each song’s meaning is provided in the liner notes.) The meaty instrumentals underscore this or help emphasize the finer points of his tales. And Jah Wobble’s Salah Dawson Miller, excels with aggressive Malian percussion throughout. A note should be made that Camara also stretches out on a Ghanaian banjo called the kologo on a couple of songs. (A historical aside is that the banjo we listen to today evolved from the early African American slave-built banhjours or banjars, instruments patterned closely after the gourd-body versions found in their homeland.)

Some may scoff at the interpolation of American electric blues into the “traditional” African soundscape, but here you can almost feel the roots of the blues, percolating below the familiar melodies, and connecting some of the dots amongst the broken, crooked lines that brought it to where it is today. At other times, it’s a jam session with Camara’s ritti trading leads like a modern blues harp would, jumping in and out of the melody alongside Adams’ guitar work. It’s easy to see why the initial meeting became a rapid formation of two musicians connecting, as the twain and twang of their stringed instruments propelled them into each other’s oeuvre. Adams production allows ample room for Camara to wax poetic as singer and orator.

The first song, Sahara, opens like it could be an old Jimmy Page or Jimi Hendrix lost gem if not for the ritti snaking around the rhythms. It breaks open to Camara’s vocals and then soars as guitar, ritti and percussion begin to pound then roar away to the very end. Tonio Yima rolls with the signature Harpo-esque rhythm and some stinging guitar slides added along the way. Mimi Suleiman applies chanted choral presence with some looped in Camara baritone chants. In Kele, Kele, Bo Diddley might have found this drum heavy beat to his liking. The patted or pattin’ juba beat that Diddley came up with from church hymns and slave work songs, takes off as the musical backdrop for Camara’s plea for Gambians and other natives of the continent to not abandon mother Africa. The ghost of Muddy Waters stands up and gets a ritti homage in Fulani Coochi Man. Here Adams openly takes the classic Waters’ guitar riff and lets Camara wail out in Fulani, although where Muddy was boasting of sexual prowess, Camara instead gives a griot lecture on the evils of greed and the resulting plight of the poor. Adams stays out of the way of Camara’s vocals and the ritti on Ganaiko, a trance-like dirge dedicated to youth who, Camara insists, must look to their roots for guidance. The ending song, Futa Jalo, a ballad, again with a message of nostalgia and dedication to ancestors, is the simplest of songs, but seems to be the sweet icing on the cake after this heavy meal of west African/American blues, and healthy sides of R&B, rock and a spoonful of trance.

This is intercontinental post-modern blues for those that embrace the hybrid music that now seems to join many a musician, from all corners of the world, together. If you are a purist, and like your ethnic tunes as close to the genre hip as possible and with no hyphens in between the classifications, then you would be better off poring through each African country’s designated CD bin (old school or online). The irony of all this, like the aforementioned banjo-banjar connection, is that the cross-pollination of instruments already happened many years ago. Was it when the diddley bow (African one-string guitar) became, symbolically speaking, Bo Diddley’s patented rectangular electric Gretsch axe? And over time, when that “electrified” guitar crossed the oceans, caravanned across deserts, trudged over the savannahs, and into the jungles, becoming a staple instrument of Africa’s benga, soukous, juju, and highlife music, the instrumental trade seemed to be complete. And yet, there still seems to be a lot of room for the blues to speak thru the plethora of African traditional instruments and the multitude of rhythm-based arrangements.

In any event, it’s easier to just sit back, listen and enjoy this recording rather than debate whether the