JOHN MCCUTCHEON AT PASADENA FOLK MUSIC SOCIETY

JOHN MCCUTCHEON AT PASADENA FOLK MUSIC SOCIETY

Caltech Beckman Institute Auditorium

Saturday, November 10, 2018 8:00pm

VIRGINIA’S RUSTIC RENAISSANCE MAN

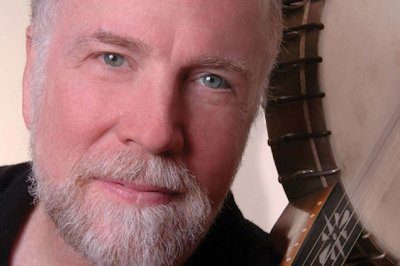

John McCutcheon’s web site puts it right out there on Front Street: No name, just www.folkmusic.com–who does he think he is? One wonders. And as with Smuckers, one concludes, “With a name like folk music, he has to be good.” And just like the sign says, he is. John McCutcheon may be our most gifted and committed folk singer since Pete Seeger passed away. He performs on pretty much all instruments one associates with folk music, going back and forth from 6 and 12-string guitars, to 5-string banjo, to hammer dulcimer, to keyboards, fiddle, autoharp and Jew’s harp —a multi-instrumentalist who is not just good but a virtuoso on all of them. He was born in Wausau, Wisconsin, August 14, 1952.

John McCutcheon’s web site puts it right out there on Front Street: No name, just www.folkmusic.com–who does he think he is? One wonders. And as with Smuckers, one concludes, “With a name like folk music, he has to be good.” And just like the sign says, he is. John McCutcheon may be our most gifted and committed folk singer since Pete Seeger passed away. He performs on pretty much all instruments one associates with folk music, going back and forth from 6 and 12-string guitars, to 5-string banjo, to hammer dulcimer, to keyboards, fiddle, autoharp and Jew’s harp —a multi-instrumentalist who is not just good but a virtuoso on all of them. He was born in Wausau, Wisconsin, August 14, 1952.

His concert is an amazing show with no filler—each song is a standout—as are his introductions and running commentary after the songs. You wind up feeling that you have been immersed in the best America has to offer in the way of traditional music and cultural representation—from Irish immigrants to Native American music and story to African-American secular songs and spirituals to Appalachian ballads to recreations of traditional songs in his own pen—to the most fully realized tribute to his mentor Pete Seeger. It was a spectacular concert that earned every minute of his long standing ovation and two encores he was generous enough to add to a 2 and 1/2-hour show—a joyous affair that made one a believer in the power of song to change the world.

The highlight of the evening came near the end—an unstated tribute to the centennial of Armistice Day following on Sunday, November 11—100 years after the end of World War I at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918. McCutcheon has written one of the classic songs of World War 1—his Christmas In the Trenches for the famed Christmas Truce of 1914 on which troops from both sides of the trenches between them put down their arms and filled with the spirit of the holiday sang Silent Night and O Holy Night and other carols to a better and peaceful world. His song is based on the true story of British soldier Francis Tolliver and concludes with Thomas Hardy’s thought from the poem The Man He Killed; written in 1902: that on both sides of the gun two soldiers are much the same:

My name is Francis Tolliver, in Liverpool I dwell

Each Christmas come since World War I, I’ve learned its lessons well

That the ones who call the shots won’t be among the dead and lame

And on each end of the rifle we’re the same

© 1984 John McCutcheon – All rights reserved

He accompanies it on six-string guitar with an exquisite melody and finger-style arrangement that highlights each syllable of the slowly-unfolding account of Tolliver’s growing realization of what English poet Wilfred Owen called the “Futility” of war. McCutcheon’s song is a major contribution to the literature of war and antiwar poetry—just a stunning achievement.

He follows that with his tender tribute to Pete Seeger—a moving and humorous story of his conversation with Pete back in January of 2008, when Pete was invited to perform on the National Mall for Obama’s Inauguration. McCutcheon drily and wryly notes that it wasn’t the first time Seeger had performed on the Mall—except that all the previous times he had been at various protest rallies and marches against administrations going all the way back to the 1950s—to ban the bomb, end the war, and for civil rights, jobs and freedom. This time was unique in that he had been invited to celebrate the election of our first Black president—by that president. When he called Pete’s wife Toshi to congratulate him on being invited to sing there, Toshi told him that Pete wasn’t home—he was on tour—at 89 years old! John was astonished to hear this and asked Toshi to give Pete the message so he could call him back if he felt like it.

Ten days later he received a call from Seeger—“Hey John, how the hell are you?” asked Pete. McCutcheon pursued his original purpose in calling which was first to congratulate Pete on being asked to sing at the Inauguration—after fifty years in which he had been persona non grata with his own government, despite the fact that he was America’s most famous folk singer and had served his country honorably during World War II. But then he came to the real purpose of his call—McCutcheon wanted to know—in the face of Seeger’s enormous repertoire of several thousand songs—which one of them he was planning to sing? Pete wasn’t going to go for the novel and obscure, but rather the song he got from Woody that the Weavers had popularized in the early 1950s—This Land Is Your Land. To all the folk singers across the land it was the highlight of the historic Inauguration—seeing Pete Seeger—accompanied by Bruce Springsteen—singing Woody Guthrie’s masterpiece—with even the censored verses intact:

Ten days later he received a call from Seeger—“Hey John, how the hell are you?” asked Pete. McCutcheon pursued his original purpose in calling which was first to congratulate Pete on being asked to sing at the Inauguration—after fifty years in which he had been persona non grata with his own government, despite the fact that he was America’s most famous folk singer and had served his country honorably during World War II. But then he came to the real purpose of his call—McCutcheon wanted to know—in the face of Seeger’s enormous repertoire of several thousand songs—which one of them he was planning to sing? Pete wasn’t going to go for the novel and obscure, but rather the song he got from Woody that the Weavers had popularized in the early 1950s—This Land Is Your Land. To all the folk singers across the land it was the highlight of the historic Inauguration—seeing Pete Seeger—accompanied by Bruce Springsteen—singing Woody Guthrie’s masterpiece—with even the censored verses intact:

As I went walking

Out on my highway

I saw a sign say

No Trespassing

But on the other side

It didn’t say nothing

That side was made for you and me.

Wow! If you didn’t believe that a song could change the world before—it was hard to deny now. There was living proof. All the blacklisters from HUAC who had destroyed the Weavers and Pete Seeger’s career having long since disappeared into the dustbin of history—there was Pete standing proudly on the National Mall—“America’s Tuning Fork,” Carl Sandburg had called him—singing Woody’s hymn to America and the disenfranchised Dust Bowl refugees from the Great Depression. It was worth waiting for, John McCutcheon eloquently concluded—after singing and playing it so beautifully on his mellow autoharp; almost too beautiful for words.

For his second encore after that he returned to Woody’s song-bag, only this time a song we had never heard before—one that Woody’s daughter Nora invited McCutcheon to set to music from the literally thousands of unfinished and unset-to-music lyrics she found after his death. It was a gem that McCutcheon had first tried to find a melody for ten years ago—but wasn’t ready to complete. It took him ten years to realize that Woody had started to write a song about his own death—and how he wished to be remembered. McCutcheon let his audience know that he had to get closer to his own sense of mortality himself before he could do justice to that theme. And now, at 66, he found to be the right time—and finished Woody’s song in the spirit in which it was begun. The irony was that it brought Woody back to life—even as he contemplated his own death—a wonderful reflection on the afterlife. Woody’s life was shortened by Huntington’s Chorea, but he lives on in his songs. His indomitable spirit shines through both his masterpieces and unfinished work.

The Washington Post describes McCutcheon as Virginia’s rustic Renaissance Man. It turns out to be a perfectly drawn portrait-in-miniature, in that John writes close to home, as well as far away. His recent album Ghost Light—drawn from an old memoir title by New York Times theatre critic Frank Rich—is based on the superstition that if an emptied theater is ever left completely dark, a ghost will take up residence. Therefore a small light must be left on stage 24/7 to prevent the ghost from inhabiting the space—perhaps from Hamlet’s ghost. McCutcheon’s haunting album is thus filled with ghosts—and his songs are the small light that keeps them in place. One is from his Virginia home—Charlottesville—where he lived for 20 years and raised his children—now best remembered as the site of the notorious attack on Jews and other counter-demonstrators to the White Nationalist Trump supporters—one of whom drove his car into the crowd and murdered activist Heather Heyer by running her over. McCutcheon wrote a brilliant protest song about the incident from the point of view of a World War II veteran watching from the sideline, and asking himself if this is what he had fought and risked his life for. He comes to the recognition that his sacrifice is symbolized by the sign on Woody Guthrie’s guitar—“This Machine Kills Fascists”—and that the war is not over—he is still ready to fight fascists and Neo-Nazis. The song is called, This Machine.

On the eve of Pete Seeger’s Centennial year (May 3rd, 1919—January 27, 2014), it is not surprising that McCutcheon’s most recent album is entitled, To Everyone In All the World: A Tribute to Pete Seeger. John is that rarest of performers—a real folk singer who still sings real folk songs, and carries on the legacies of those who came before. He is a songwriter with a profound historic sense of what Phil Ochs called the links on the chain. One such song he performed tonight is a song from the Industrial Ballads collection Pete once recorded—Peg and Awl—a traditional song about shoemakers. John introduced it with a charming anecdote about searching for years to find “all the songs” he could about shoemakers. And he found just one. As my old mentor philosopher John Macksoud once wrote, “The search is more important than the meaning.” So the one song he found McCutcheon sings with love—the first time I have heard anyone besides Pete sing it. That’s tradition!

Bravo to John McCutcheon for putting in the simplest possible terms what inspires America’s truth-tellers—and folk singers—to keep speaking truth to power.

These are our Gatekeepers of Freedom—our witness-bearers to the sacred American values which Pete Seeger represented and embodied for more than sixty years—and performers like John McCutcheon have now inherited and carry on.

Nobody carries this light with more distinction than John McCutcheon. From Joe Hill to Woody and Pete, to John, the mantle he wears still glows in the dark. Bravo!

Thanks to Rex Mayreis and Nick Smith of the Pasadena Folk Music Society for the press pass.

Folk singer Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature from SUNY-Binghamton; he belongs to Local 47 AFM; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com