JOHN HAMMOND – MCCABE’S – SEPTEMBER 29, 2017

JOHN HAMMOND

AT MCCABE’S – SEPTEMBER 29, 2017~THE LATE SHOW

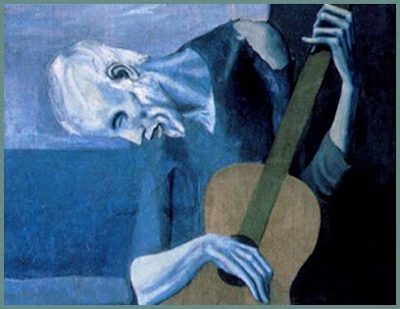

THE MAN WITH THE BLUE GUITAR

“They said you have a blue guitar~ you don’t play things as they are…” Wallace Stevens

“They said you have a blue guitar~ you don’t play things as they are…” Wallace Stevens

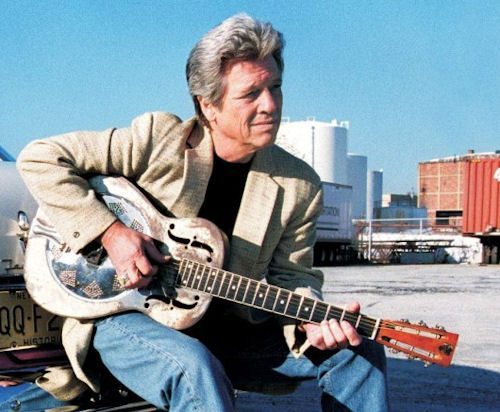

The man with the blue guitar descended the staircase and walked onstage with a shock of white hair and a big smile.

I’ve been to the mountaintop—I’ve looked over—and I’ve seen the Promised Land—and John Hammond was playing the blues. Welcome to McCabe’s last Friday night—September 29, 2017, Yom Kippur. The Day of Atonement if you’re Jewish, and if you’re not, well listening to John Hammond you can’t help but feel you are atoning for something. Belying that welcoming big smile his voice hits so many notes of pure anguish only a rabbi could tell the difference. Whatever his sins may have been, his soul-wrenching cross-harp harmonica, note-bending finger-style blues unplugged acoustic guitar and single cone resonator playing bottle-neck slide guitar would have melted the Lord’s heart. It certainly melted mine.

John Hammond has been performing professionally since 1962, the same year Bob Dylan started, and both put their stamp on the “white blues singers” who descended on Greenwich Village—along with Dave Van Ronk (who preceded them) and Roy Book Binder, who followed. Hammond is the son of John Hammond, Sr., who “discovered” Dylan—and before him Billie Holiday—and after him Bruce Springsteen—and more to the point rediscovered and released the rare and incomparable legendary 29 sides Robert Johnson recorded in 1936 and 37—King of the Delta Blues—in 1961. One of the highlights of Hammond’s show tonight was Johnson’s Come On In My Kitchen. If you heard nothing else you would have experienced the blues down to the souls of your shoes. It was riveting and piercing in a way that ordinary language has a hard time describing. Hammond is not only a great guitarist and harmonica player (in the tradition of Sonny Terry), he is a great singer who fully captures the best of the black blues singers whose stories he relishes in telling, whose names he remembers and celebrates, and whose songs he now carries on to several new generations of listeners and musicians. He lets us know he made a documentary about Johnson called In Search of the Delta Blues, which reminds me of the Paris Review program I reviewed at Beyond Baroque, which promoted the idea that the blues was not necessarily a black art form. I have no doubt that Hammond’s search for the blues did not lead him to a white Victorian songwriter from Indiana, but to Clarksdale, Mississippi and the crossroads of Highways 49 and 61.

One audience member after the show said within earshot, “I loved his singing and playing, but if he had just sat there and never picked up his guitar and sang a song, I still would have been just as happy—that’s how great a storyteller he is.” She understood how Hammond is far more than a great performer—he is the living link to a great tradition—one in danger of disappearing were it not for performers like Book Binder and David Bromberg and Hammond himself—and a few black performers as well, like Keb’ Mo’ and Taj Mahal and Robert Cray—interpreters of America’s greatest music—the link to jazz on the one hand and African-American spirituals on the other.

They are the reasons we still remember the names and appreciate the music of John Lee Hooker, Skip James, Son House, Robert Johnson, Howlin’ Wolf, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Willie McTell, Blind Blake and Blind Boy Fuller—who discovered Blind Sonny Terry one day on the opposite side of the street—playing harmonica and pulling Fuller’s audience from the side he was used to holding forth. Fuller recognized a genius when he heard one and decided he would do better if they joined forces and became a team. And they did, until Fuller passed away a few years later—when Sonny Terry met Brownie McGee and they became the most popular blues duo in the country. Hammond holds them forth like precious works of art to let shine once again. He keeps them alive in the fullest sense of the word. He transmutes their suffering into some version of pure joy that emanates from their artistry—and the life stories that give depth and breadth to their music. But he never reduces them to museum pieces—he becomes their suffering as well—he doesn’t simply present it—he has lived it to his bones—and every song he sings makes the blues a living tradition. You can see it in his face and hear it in his voice—you can even sense it from watching his fingers embrace every fret of his amazing David R. Stubbs OM vintage acoustic guitar from the lowest bass to the highest treble strings. It is truly what Harry Chapin once called a six-string orchestra.

Guitar maker David R. Stubbs is a boat builder in Cumbria in the UK; thirty-five years ago he took a break from building boats to build guitars and after he had made nineteen, went back to boats—due to the fine dust effluvia from the guitars exacerbating his asthma. John Hammond put them on the map of legendary contemporary guitars—and the other eighteen anonymous guitarists maintain their own page on the Guitar Forum trading stories about how they found them. To them Stubbs is the Stradivarius of luthiers—and listening to Hammond play one can easily hear why. Without a pickup—just a single microphone placed by Wayne Griffith, their incredible sound engineer, Hammond fills the hall with a prophetic glorious guitar voice that is like a fully animated second performer playing off of every note. It’s a sonic masterpiece that holds your heart in his hands from beginning to end. His Sonny Terry-like harmonica adds yet a third voice to the ensemble and at some point you realize you are listening to a blues trio, not a single performer. It’s haunting and beautiful, sad and strange.

In the foyer before the concert I overheard some guests reminiscing about how and when they had first heard Hammond—back in Rochester, New York. “I have a picture of him from 1960,” said one, “and I hope he knows who I am.” Another seems to be a Mercedes Benz dealer, who hasn’t forgotten where he came from. There are only two recognizably black members of the audience—a man and a woman—who aren’t sitting together. But they stand in for the black artists who created this music—of, by and for the people. John Hammond didn’t break his rhythm to burden the audience with any political asides or comments, and yet the authenticity and integrity of every word and note he spoke or sang made an eloquent speech of its own—they rescued the English language from the deception, lies and mendacity that have become all too commonplace this political season. Indeed, the one original song Hammond included in this great concert addressed this very issue; it was his homage to white bluesman Mose Allison and could have been addressed to the president himself: Eyes In the Back of My Head, which laments with a wry eye that to keep track of all his alternative facts and distortions of reality you’d have to have eyes in the back of your head. It’s Hammond’s moral parable, and is unmistakable in its razor sharp delineation of today’s “power elite,” with thanks to C. Wright Mills. Allison wrote his own version of this surgically precise counterstatement to the president’s propaganda machine with Your Mind Is on Vacation, (But Your Mouth is Working Overtime).

Hammond sings straight from the heart—there is not one phony word to make one doubt his honesty. If Honest Abe Lincoln were a blues singer, this is how he would sound. It almost restores one’s faith in America just to be able to revel in their naked unafraid heart-baring lessons in how to live without hidden agendas and secret ambitions. See That My Grave is Kept Clean, wrote Blind Lemon, and he stands before you in the voice of John Hammond—as if he had never died. He plays it in drop D-tuning, with Stubbs’ deep bass strings and a thumb pick carrying the plaintive cry of “One kind favor I ask of you, see that my grave is kept clean,” a song Dylan also sang on his first album.

He does a special tribute to Charlie Patton, “Father of the Country Blues,” with How Many More Years are You Gonna Wreck My Life? and Stone Pony Blues. The major difference between Dylan and Hammond after fifty years of performing is that when Dylan wants to honor Charlie Patton or Blind Willie McTell he writes a song for them; Hammond honors them by still singing their own songs. To my ears that still rings true. Their music is in good hands.

One of the unexpected gems of tonight’s concert is his delightful story about Ed Pearl and the Ash Grove—from his first appearance there in the early sixties. Ed called him all the way from California to the New York Island and asked him, “How’d you like to open for Howlin’ Wolf?” Wow! It was a magic moment for Hammond, who was in his car and driving across country practically as soon as he hung up the phone. The Ash Grove was sold out for five nights in a row for Wolf, but Wolf didn’t show up for the first night—he was having car trouble on the road. Hammond was already very nervous for his 25-minute set, and barely got through it when he saw Pearl in the doorway stretching his hands out with a desperate look on his face—meaning “keep on singing—Wolf isn’t here!” Hammond wound up singing three more songs—which at that point was his entire repertoire—before he realized that Wolf was finally in the building. But the real highlight was yet to come: after the show Howlin’ Wolf asked him, “How’d you learn to play like that?” perhaps expecting to hear some version of Robert Johnson’s “sold my soul to the devil at the Crossroads” tale. Instead, as always, Hammond told him the truth: “Listening to records.” And then Wolf surprised him too: “Hmm—me too!” That sealed their friendship ever since, and they wound up playing together like two old bluesmen.

This week is a special one for this student of literature and folk music—October 4, 2017 will be the 80th anniversary of the publication of American poet Wallace Stevens’ The Man With the Blue Guitar, October 4, 1937, inspired by Picasso’s painting The Old Guitarist, from Barcelona in 1903. It will be the title song of my upcoming CD, adapted with my music. So I can’t help but think of it in connection with this great modern blues master; for if anyone is “The man with the blue guitar,” it’s John Hammond.

His final song of the night, fittingly enough, is Preaching the Blues, by Son House. Hammond shares this wonderful story about him before leaving us with his blues anthem; during the Great Depression he had to make a living and he quit performing and recording to work a day job for the next thirty years. But once the folk revival began in the early 1960s, and young folk singers fell in love with the classic black blues men of the early 20th Century, they wanted to invite them to the Newport Folk Festival to perform. One of them was Dick Waterman, who was disappointed to find that Son House had no interest in performing again: “I have forgotten all my old songs and couldn’t play them anymore.” Well, Waterman knew a sixteen year-old guitarist and 78-record collector named Al Wilson, who had all of Son House’s old records, and could play his songs. Waterman put Son House together with Al Wilson—who taught him how to play his old songs—and then brought him to Newport for the Blues festival in 1964. And now fifty years later John Hammond keeps the whole rhapsodic tale alive—and for Son House and a whole generation of American blues masters, continues “Preaching the Blues.”

The audience rose to their feet as one, and begged for an encore. But then from imagination’s highest rung, reality set in. Hammond looked out and confided that he was spent—he had no more to give. “I’m going to be 75 next month.” And this was the second sold out show of the night. “I can’t do anymore.” He is so gracious in referring to McCabe’s as “an institution,” and expressing his gratitude to the audience for coming out to see him again. He understands what a privilege it is to make one’s living doing what one loves. He doesn’t take any of it for granted, and makes us feel an essential part of the show. Like a great athlete, he doesn’t save anything for the locker room. He leaves it all on the field. As he climbs that legendary staircase up to the green room the audience keeps on applauding. And an old speech, from April 3rd 1968, suddenly comes to mind.

To some it is only McCabe’s on a Friday night, but to me it’s like being in temple. In the words of the preacher himself, “I have been to the mountaintop. And I have looked over, and I have seen the Promised Land.” What I have seen is the man with the blue guitar—John Hammond on Yom Kippur—still preaching the blues, but more than that.

“…The man replied: ‘Things as they are~ are changed upon the blue guitar.’”

~Wallace Stevens (October 2, 1879 – August 2, 1955)

With many thanks to McCabe’s Concert Director Lincoln Myerson for the press pass.

Blues singer and guitarist Barbara Dane, another protégé of Ed Pearl’s legendary folk club The Ash Grove, performs at UCLA’s Royce Hall Saturday October 21 at 7:30pm with yet another protégé of Ed’s West Coast University of Folk Music—The Chambers Brothers. They appear under the auspices of UCLA’s CAP program; 310-825-4401.

Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature from SUNY-Binghamton; he belongs to Local 47 (AFM); Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com