IN SEARCH OF THE FIRST BLUES SONG

IN SEARCH OF THE FIRST BLUES SONG:

“…Touched down in the land of the Delta Blues, in the middle of the pouring rain. W.C. Handy, won’t you look down over me?” (Walking in Memphis, Marc Cohn, 1991)

“…Touched down in the land of the Delta Blues, in the middle of the pouring rain. W.C. Handy, won’t you look down over me?” (Walking in Memphis, Marc Cohn, 1991)

“William Christopher Handy (November 16, 1873 – March 28, 1958) was an American composer and musician, known as the “Father of the Blues.”” (Wikipedia) And they might have added for the record; W.C. Handy was African-American. “I hate to see that evening sun go down.” Is Pluto about to get demoted? There’s only one way to find out.

A curious incident of historical revisionism made its appearance at Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center last night—the last place in the world I would have expected a polite white Southerner—of the most decorous kind—to be welcome with a brand new theory of the origin of The Blues—specifically in search of “the first blues song.” He illustrated his lecture with sheet music going back to 1887 in the late 19th century, deliberately and scholastically predating the “first blues song” according to most all standard references (including my recent FolkWorks review of Roy Book Binder’s concert at McCabe’s on the subject, which cite W.C. Handy’s St. Louis Blues from 1914. Here is the promo:

“Join the editors of

The Paris Review is a quarterly literary magazine established in

“The Paris Review hopes to emphasize creative work—fiction and poetry—not to the exclusion of criticism, but with the aim in mind of merely removing criticism from the dominating place it holds in most literary magazines. […] I think The Paris Review should welcome these people into its pages: the good writers and good poets, the non-drumbeaters and non-axe-grinders. So long as they’re good.” (William Styron, premiere issue Spring, 1953, for the editors.) As someone trained in criticism I take particular offense at this slight.

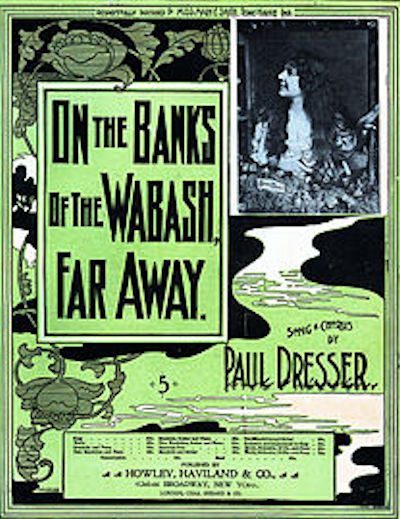

By the time John Jeremiah Sullivan got to the end of his presentation he was saying, and I quote, “There is really no such thing as “the blues;” “we really should get rid of the term altogether—it’s done more harm than good,” and “the blues is if anything a hybrid of black and white,” such that by the second half of his talk he was citing that well-known blues composer of white Victorian sentimental ballads Paul Dresser (novelist Theodore Dreiser’s older brother) as the beginning of “the blues.” My ears were in such a state of rebellion that I could not even frame a question during the Q & A without sounding like a belligerent loudmouth, so I held my tongue and took my notebook out of my pocket.

Before the end the single black member of the audience stood up and hesitantly asked a question: “How do you define the blues?” The presenter announced from the authority of the podium, “You can’t really define the blues.” No one—including the questioner—had the temerity to protest. The first words on the tip of my tongue were from Supreme Court justice John Paul Stevens, who once replied in a comparable situation—regarding a case that turned upon whether a particular film should be considered “pornographic”—“I can’t define pornography, but I know it when I see it.” How often have I recalled his sagacity?

I can’t define the blues, but I know it when I hear it. And Paul Dresser is not the blues. I wish Lightning Hopkins had been there last night. I wish Blind Lemon had been there. I wish Reverend Gary Davis had been there. I wish Blind Willie McTell had been there. I wish Lead Belly had been there, who once said, “Never was a white man had the blues.”

As someone with a profound respect for the Paris Review, I was thrown off my game by seeing that this program was presented as a collaborative effort between Beyond Baroque and the most revered literary quarterly in the world. As it turned out the literary quarterly was—I kid you not—Matthiessen’s front for Plimpton’s work as a CIA agent. That’s why Matthiessen created it. The entire tawdry tale is now in the public domain, and spelled out on Wikipedia. The best part of the Paris Review is a four-part series of interviews with famous writers called “Writers at Work.” Fast forward to the present, when the Paris Review is now based in

The presenter John Jeremiah Sullivan is a widely published and highly esteemed essayist and the Southern editor of The Paris Review. So I put this out on front street~ to let our readers know that if prestige is enough to score points in an argument, I readily grant that all the prestige is on the side of The Paris Review and its Southern editor’s quixotic claim that the blues—one of three black American art forms that have represented the best in America culture to the rest of the world—the others being jazz and Negro Spirituals—is now to be regarded as a black/white hybrid which grew out of the sentimental songs of the 1890s. I practically choke on these words as I write them. It is decorous nonsense.

The presenter John Jeremiah Sullivan is a widely published and highly esteemed essayist and the Southern editor of The Paris Review. So I put this out on front street~ to let our readers know that if prestige is enough to score points in an argument, I readily grant that all the prestige is on the side of The Paris Review and its Southern editor’s quixotic claim that the blues—one of three black American art forms that have represented the best in America culture to the rest of the world—the others being jazz and Negro Spirituals—is now to be regarded as a black/white hybrid which grew out of the sentimental songs of the 1890s. I practically choke on these words as I write them. It is decorous nonsense.

How do I know? Because I took Prof. Ralph Rader’s brilliant class in the novel at UC Berkeley in 1973—and learned once and for all what it takes to defend a thesis in criticism. I wandered along the corridor of graduate English classes eavesdropping on professors asking students for their opinions on the subject at hand. When I finally reached the front door to Prof Rader—who wrote for the journal Critical Inquiry— he didn’t ask students for their opinion—in a booming voice he told them what he knew—fruit of years of research. I found my professor. Hemingway said that the one thing a writer needs is a good B.S. detector, and thanks to Prof Rader mine is in good working order. What I learned from the good doctor is that when a consensus has emerged on a particular subject it deserves the presumption of truth—and your responsibility if you challenge it is to bear the burden of proof required in a court of law. Your mere opinion is not sufficient. That’s why he never asked for it. Professor Rader’s field was the history of the novel, but it applies equally well to the history of the blues. That’s why criticism is important; it teaches you the art of analogy. And critic Kenneth Burke’s pentad of dramatism, scene, act, agent, agency and attitude, and how their “ratios” affect each other in dramatic situations, and what he calls “symbolic action,” illuminate even this quest.

Is the blues black? Were the Negro Leagues? Are the

But John Jeremiah Sullivan did make an argument; and in memory of my late Jesuit-trained mentor Professor of Rhetoric John Macksoud—who taught me to debate someone only if you can make their own argument at least as well as they do, let me restate it here: Creole jazz pianist Jelly Roll Morton had a famous encounter with folklorist Alan Lomax in which he recorded two ways of playing Paul Dresser’s most popular song My Gal Sal; the first time through he played it straight, as Burl Ives sang it, a white sentimental ballad of 1905; but then he jazzed it up—as if he himself had written it like the Jelly Roll Blues he recorded in 1915 (one year after W.C. Handy’s St. Louis Blues of 1914)—and which he accordingly bragged about as “the first jazz song”—Sullivan’s point being that “the blues” is not necessarily a specific song, or even a style of song, but rather a way of playing a song—and that therefore (here is the argument’s conclusion) Paul Dresser might have written “the first blues” in 1887, when he wrote The Curse of the Dreamer.

But John Jeremiah Sullivan did make an argument; and in memory of my late Jesuit-trained mentor Professor of Rhetoric John Macksoud—who taught me to debate someone only if you can make their own argument at least as well as they do, let me restate it here: Creole jazz pianist Jelly Roll Morton had a famous encounter with folklorist Alan Lomax in which he recorded two ways of playing Paul Dresser’s most popular song My Gal Sal; the first time through he played it straight, as Burl Ives sang it, a white sentimental ballad of 1905; but then he jazzed it up—as if he himself had written it like the Jelly Roll Blues he recorded in 1915 (one year after W.C. Handy’s St. Louis Blues of 1914)—and which he accordingly bragged about as “the first jazz song”—Sullivan’s point being that “the blues” is not necessarily a specific song, or even a style of song, but rather a way of playing a song—and that therefore (here is the argument’s conclusion) Paul Dresser might have written “the first blues” in 1887, when he wrote The Curse of the Dreamer.

But it doesn’t pass the smell test. Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil, not Paul Dresser. And Dresser didn’t invent the blues; W.C. Handy did. How do I know? Lead Belly, who sang his way out of prison twice, told me so: “Never was a white man had the blues.”

Of course, since roughly 1960, white blues singers have probably sold more records of the blues than their forebears from whom the art form derived—going all the way back to the Negro Spirituals of the pre-Civil War era. You can name them as well I: Elvis, Dave Van Ronk, Bob Dylan, John Hammond, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Roy Book Binder, David Bromberg, Bonnie Raitt, and Maria Muldaur, and over in England, the Beatles, Rolling Stones, the Animals and Eric Clapton—all of whom launched their careers with covers of American artists like Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Big Mama Thornton.

In 1962, both Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary recorded two great songs by Harlem street singer Blind Reverend Gary Davis—Baby Let Me Follow You Down and Samson and Delilah without credit to their composer and lyricist. Only when Manny Greenhill’s Folklore Productions intervened on behalf of Reverend Davis were his name and copyright restored. But they too were late to the ball.

In 1956, Memphis’ Sun Records founder Sam Phillips famously said, “Get me a white singer who sounds black and I can make a hit record—which he did when Elvis Presley covered Big Mama Thornton’s Hound Dog. But the historical milieu in which this search for the “first blues song” takes place predates this crossover romance of white performers for black roots music by more than half a century. John Jeremiah Sullivan is at The Road Not Taken when he stands at the crossroads of W.C. Handy’s first widely acknowledged blues song St. Louis Blues—and instead of tracing its roots back to a Negro Spiritual from the Underground Railroad like No More Auction Block Over Me or Steal Away, Jesus, or Wade In the Water veers off into the sentimental white songs of the 1890s for a tragic ballad by Paul Dresser. Black songwriters and singers have always been seen as fair game for opportunistic white performers, publishers and record companies bent on taking or assigning credit from their black sources. Without the black blues tradition—and early rock and roll it inspired—they would not have become well enough known to warrant this kind of attention.

And yet, ironically many white blues artists are now better known for carrying on primary black sources than the sources themselves. Keith Richards made a great documentary on Chuck Berry—“Hail, Hail Rock and Roll!” Reverend Gary Davis was able to purchase a decent home in Harlem—“The house that Peter, Paul and Mary built”—with royalties from Samson and Delilah. Maria Muldaur and Bonnie Raitt recorded the tribute album First Came Memphis Minnie for the pioneer great female blues guitarist who inspired them. Bob Dylan paid homage with No One Sang the Blues Like Blind Willie McTell. In 1990 Willie Nelson came out with a collection called Milk Cow Blues devoted entirely to the blues. And from way over in Ireland Van Morrison will release his blues collection “Roll with the Punches” September 22. All over the world our preeminent artists know that the blues is black—but in the American South—about which Alan Lomax wrote The Land Where the Blues Began (Pantheon Books, 1993) the Paris Review acts like Alexander Fleming never discovered penicillin. Lomax’s book recounts

“his ventures to Mississippi (and Arkansas and Memphis) in 1941-42, 1947, 1959 and 1978, including his historic sessions with Muddy Waters, Son House, Honeyboy Edwards, Fred McDowell, Sam Chatmon, Forrest City Joe, and other bluesmen, along with preachers, prisoners, levee camp workers, and fife and drum bands. Another chapter is devoted to a conversation between Big Bill Broonzy, Memphis Slim and John Lee ‘Sonny Boy’ Williamson, recorded by Lomax and released on the album Blues in the Mississippi Night.”

Following the program the rest of the authority is also granted to the presenter, since the questions are posed by the audience to the expert on stage. His answer carries the weight of the format—the audience relegated to the position of dutiful inquirer for the expert answer of the presenter. But what if the presenter were not onstage, and not seated across from his editor, and not holding a microphone? What if he were on an equal footing with the young black man asking the question—apropos of Kenneth Burke’s scene/act ratio?

If Beale Street could talk, it might have said: “Mr. Sullivan, I don’t have your reputation; I am not the “Southern Editor of Paris Review.” But I have listened to the Blues all my life, and this is what I have learned. I know it when I hear it. I have heard Robert Johnson sing, “Hellhound on my trail—blues comin’ down like hail.” I have heard Blind Lemon Jefferson sing, “Matchbox fits my clothes” and “One Dime Blues.” I have heard Big Bill Broonzy sing Black, Brown and White Blues: “If you’re white you’re all right, if you’re brown stick around, but if you’re black, Oh buddy, git back, git back, git back.’” Big Bill Broonzy was a janitor, who couldn’t have afforded the $10 to get into Beyond Baroque.”

I heard Lead Belly sing Bourgeois Blues:

Well, me and my wife was standin’ upstairs

We heard a white man say, ‘I don’t want no colored here.’

Lord, in a bourgeois town

Uhm, in a bourgeois town

I got the Bourgeois Blues

Gonna spread the news all around.

I’ll take Lead Belly any day of the week and twice on Sunday; when he told Alan Lomax:

Home of the brave, land of the free

I don’t want to be mistreated by no bourgeoisie

I got the bourgeois blues

Gonna spread the news.

The blues is black.

And that’s how I was going to leave it, until I remembered another song—this one by poet-critic Kenneth Burke:One Light In a Dark Valley (An Imitation Spiritual). It never would have gone beyond KB’s Collected Poems but for the fact that his son-in-law was—I kid you not—singer-songwriter Harry Chapin, who recorded it! And from this Harry’s recording, another Harry heard it—that would be Harry Belafonte! He recorded it too, and suddenly, Burke’s self-described “Imitation Spiritual” became the real thing—because it was performed by a great black artist who sang real spirituals—and real blues. Kenneth Burke’s critical background and integrity in acknowledging the very distinction on which this essay is based—and entitling his wonderful song “An Imitation Spiritual”—guides us out of this labyrinthine dark wood. Had he written a blues instead of a spiritual he would have put “An Imitation Blues” in parenthesis. Why—because he knew the difference between an imitation and the real thing; If Beale Street Could Talk.

But we all know that a picture can be worth a thousand words, so in conclusion I turn to a framed Patterson & Barnes painting on my wall, next to my desk. It portrays a black guitarist who reminds me of Josh White, with his wife behind him looking over his shoulder, and their teenage son and daughter off to the left, just beneath the portrait’s title—what else?—“The Blues.” All four family members are black. And except for the dark-hued blonde acoustic guitar, the color-scheme of the entire painting displays shades of blue. At the very bottom off to the left is the following inscription: “It started back when daddy lost his job. He took to drinking. Mamma tried her best but pretty soon she had enough. So we all sing the blues, wait’in on better times.” It cost me $50 at a thrift shop. It’s an original by Gary Patterson and Marion Barnes whose portraits of jazz and blues musicians are collected by Jimmy Buffet, Chris Rock and Whoopi Goldberg and would have cost over $5,000 as an unsold gallery painting. I fell in love with it immediately, before I knew who they were, but I know fine art when I see it and knew that someday it would have something meaningful to say. That pretty much says it all—better than I can.

So I wish “Empress of the Blues” Bessie Smith had been there last night. I wish Ma Rainey had been there. I wish Alan Lomax had been there. I wish Billie Holiday had been there; I heard Billie Holiday sing, “God Bless the Child.” Lady sings the blues. Only the gardenia was white.

Dedicated to Fred Holtby, who introduced me to Kenneth Burke; folk singer Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature; he belongs to Local 47 (AFM); Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com