HOMAGE TO THEO

Homage to Theo

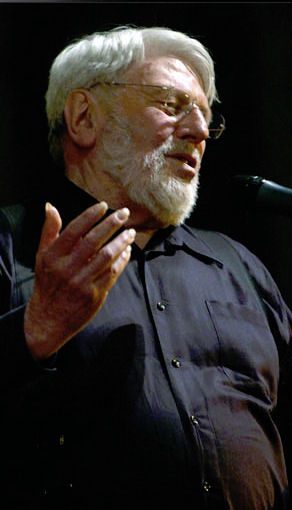

Concert Celebrating Theodore Bikel’s 90th Birthday

At the Saban Theatre in Beverly Hills – June 16, 2014

How Jewish was this event? Even the Holocaust denier out in front was Jewish. He held up a sign warning about the “Holohoax” that the “Zionists” were trying to perpetrate. He needed a nose job and twenty years of psychotherapy to get over being a self-hating Jew. I know my people. And he did too. Where would he find more Jews to rile than at a 90th birthday party for Theo? His name was on the marquee, and there were lines around the block. I asked a fellow landsman if he had tickets. “No, this is for Will Call.” I did have tickets—from the box office two months ago. Just like Eric Darling, we walked right in.

How Jewish was this event? Even the Holocaust denier out in front was Jewish. He held up a sign warning about the “Holohoax” that the “Zionists” were trying to perpetrate. He needed a nose job and twenty years of psychotherapy to get over being a self-hating Jew. I know my people. And he did too. Where would he find more Jews to rile than at a 90th birthday party for Theo? His name was on the marquee, and there were lines around the block. I asked a fellow landsman if he had tickets. “No, this is for Will Call.” I did have tickets—from the box office two months ago. Just like Eric Darling, we walked right in.

Theodore Bikel, folk singer, actor, activist and newlywed turned 90 years old on May 2nd; a few of his friends—including Arlo Guthrie, Tom Paxton, Peter Yarrow and fellow thespian Ed Asner held a little soiree to celebrate the occasion last night at Beverly Hills “Temple of the Performing Arts,” the Saban Theatre. It was a Hootenanny in the grand old tradition, with fifteen performers—including the Limelighters’ Alex Hassilev who bore an eerie resemblance to a younger Theo—taking their turns at the microphone on center stage, and politicians, labor leaders and recording executives conveying their gratitude to the man who brought (in both senses) the Sound of Music to America. We could have had better seats. If I were a rich man.

Before any live performances the show began with a visual and vivid reminder of Theodore Bikel’s extraordinary career as an actor on both stage and screen, who has been in 45 movies, with notable excerpts from The African Queen, The Defiant Ones, My Fair Lady and The Russians Are Coming, as well as episodes from Television’s Golden Age, with unforgettable appearances in The Twilight Zone and my favorite, Columbo.

It was Theodore Bikel for whom Oscar Hammerstein wrote his last song, Edelweiss. And it was Theodore Bikel who with Pete Seeger and Oscar Brand launched the Newport Folk Festival in 1959. He began recording for Jac Holzman’s new label Elektra Records in 1955, and helped put it on the folk music map with recordings of Jewish folk songs in Yiddish, Israeli folk songs and Russian Gypsy folk songs, as well as musical theatre songs—preeminently in the role of Tevye in Fiddler On the Roof, which he performed more than two thousand times on Broadway, across the country and around the world.

Last night it was Theodore Bikel at 90 who still sang louder, longer and with more guts than all the better known folk singers put together whose careers he helped inspire with his commitment to social justice as part and parcel of the folk singer’s mission, passion and basic job description. But Theo did not just sing about these issues: he has been a union organizer and labor leader as head of the Actor’s Fund, and helped oppressed Soviet Jewish dissident poets and songwriters get their work out of the Soviet Union. Retiring County Board of Supervisors’ 3rd District’s Zev Yaroslavsky recounted the time when as a student at UCLA he called on Theo Bikel to give them support in smuggling some of their work out of the USSR, where it was passed around in the form of Samizdat, the underground distribution method for artists who dared to challenge the orthodoxy of communism and risked their freedom in so doing.

When the student group got him copies of their texts—which were only preserved on cheap typescripts and copied from hand to hand—Bikel recorded a dozen of them for a small label in America and got them smuggled back into the Soviet Union to give them new life and a broader audience. Yaroslavsky came to pay tribute to Bikel’s willingness time and again to give voice to the voiceless and some measure of respect to the powerless. It was a moving moment to see Zev lean over and lightly kiss Theo’s cheek in thanks—as a now old student to his one-time mentor.

Other non-musicians also made an impression with their spoken tributes, for one and all they introduced themselves as having something in common with Theo: they too had played Tevye—only in the third or fourth grades. They felt honored to finally meet the real Tevye, whose theme music (If I Were a Rich Man words by Sheldon Harnick and music by Jerry Bock) was the overture to the entire evening. The last of these was Mark Pinkus, Senior Vice President of Rhino Records who came to this birthday party bearing gifts—specifically the announcement that Rhino would be reissuing a dozen of Theodore Bikel’s classic 1950s and 1960s Elektra albums on iTunes, to preserve his matchless voice for the 21st Century as well. The release date is July 22nd.

Tom Paxton was the first of the visiting folk luminaries to capture the spirit of his fellow Elektra recording artist with a song that touched on all the themes that galvanized the 1960s civil rights and antiwar movements—and to link them to the Jewish prophetic tradition with the words of Isaiah: How Beautiful Upon the Mountain (Are the Steps of Those Who Walk in Peace). Evoking both Martin Luther King’s Selma-to-Montgomery March of 1965 that led to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the March on the Pentagon of 1967 in which Abbie Hoffman famously “levitated” the Pentagon and introduced Pigasus to the peace movement as their own “candidate for president.”

Paxton’s beautiful lyric and heartfelt performance elevated the level of the musical performances to give voice to the themes of Bikel’s own life—who while a generation older reached out to the student activists of the time with an open hand and heart. Then Tom generously dedicated The Honor of Your Company—his tribute in song to that earlier generation of folk singers like Pete Seeger, the Weavers and Theodore Bikel himself to the evening’s 90-year old guest of honor. As he so often does Tom Paxton is able to bring a folk-seasoned sensibility to a new song that makes it sound a part of the tradition—as his early songs like Rambling Boy and The Last Thing On My Mind have indeed long since become.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-LAMA4trapI

Peter Yarrow regaled the audience with an Arlo Guthriesque tale of how he had tried to rewrite Puff the Magic Dragon with a happy ending so it wouldn’t make you cry —having just gotten worn down by the river of young tears this most unlikely children’s classic has triggered over the years. He disarmed the sold-out packed Saban Theatre audience of fans who had no doubt grown up on this very song by saying “I know you don’t want to hear it again,” (to which he received a resounding “Yes we do!”) before giving the final vote to Theo’s new wife Aimee Ginsburg Bikel (married December 29, 2013)—who specifically requested the song of Peter. He could not disappoint her, and had the whole theatre joining him from the first words to the last.

Peter Yarrow also took the opportunity to once and for all disabuse his fans of the foul canard of folklore the song itself has inspired—that the song was about drugs and smoking marijuana. He reassured us that “Puff” had nothing to do with “puff.” Yeah, sure, with a twinkle in his eye; Peter’s was a magical performance about a magic dragon. He then followed that with an impassioned plea for peace in the Middle East and sang his popular Hanukah song Light One Candle. The audience ate it up like a plateful of latkes, but Linda turned to me at the end and asked with a profound simplicity, “Can you imagine a Palestinian singing that song?” With one devastating question she zeroed in on the reason that “peace in the Middle East” is still a distant prospect at best.

Arlo Guthrie did not even have to be introduced: a groundswell of applause greeted him as soon as he rose up from the phalanx of chairs set up on stage so all the artists (except for Theo Bikel) were in full view of the audience during the whole show. As he strolled towards the microphone one almost started laughing just in anticipation of what he might say. It wasn’t long, as he paused right after starting his first song to start fiddling with his beautiful Martin D-35 (with a gorgeous three-piece back of what shone like Brazilian rosewood when he turned around) and say in mock frustration: I always forget to plug in my “acoustic” guitar—commenting on the hypocrisy of folk singers bragging on their so-called acoustic guitars which are now regularly played with pick-ups.

Without mentioning her name he started talking about his “Bubbe,” (Jewish for grandmother) and how she had influenced him without him knowing it. Arlo, you see, is also Jewish, since his mother, Woody’s second wife, was Marjorie Mazia, a dancer with the Martha Graham Modern Dance Company. And her mother—his “Bubbe”—was the highly regarded modern Jewish poet, Eliza Greenblatt. (Kinehora, would it kill you, Arlo, to mention her name?) What Arlo did say was she finally got his attention when she took him to see Theodore Bikel in concert and one of the Yiddish songs he performed was—she told him, beaming with pride—written by her. Now he knew who she was.

After singing two lesser known songs with lyrics by his father (one, a song about Woody’s mother set to music by Janis Ian, and My Peace, a song Arlo set to music), Arlo brought everyone together on stage for This Land Is Your Land set in what “Pete called ‘the people’s key’ G,” and they focused on the additional verses Woody taught his young son so they wouldn’t be forgotten—since there wasn’t room for them in the schoolbooks of the time. Paxton sang the hard times verse, and brought it up to date:

In the middle of the city

By the shadow of the steeple

By the relief office [Paxton modernized it to “welfare office”]

I saw my people

They stood there hungry

I stood there wondering

If this land was made for you and me.

I found this the most moving verse of the song, and with Arlo leading his dad’s most famous chorus it brought the first half of the show to a resounding close.

Which is not to say there were no sour notes in the many musical tributes we heard—ironically enough in the very idiom most closely identified with Theodore Bikel himself—Yiddish folk song. But first Cathy Fink and Marcy Marxer performed an outstanding previously unheard Woody Guthrie song—once again, as with the two Arlo did—with Woody’s unearthed lyrics which his daughter Nora Guthrie has been assigning to a wide-ranging number of contemporary folk musicians to set to music. Cathy and Marcy gave his children’s nonsense lyrics an engaging up-tempo tune that was remarkable for their virtuosity on a double banjo accompaniment—with Cathy playing the clawhammer melody notes and Marcy providing harmony on her banjo bass. It aroused as much applause from their fellow performers on stage behind them as the audience out in front. One could only marvel at the musicianship which has earned them two Grammys.

But no doubt due to the presence of the master of Jewish folk song they felt inspired to present a song from that repertoire as well—one of the best, and thanks to the legendary all-women’s East European folk ensemble The Pennywhistlers—who recorded it on their collaborative album with Theodore Bikel—one of the best known. That is Morris Rosenfeld’s masterpiece Main Rue Platz (“My Resting Place”), the best evocation of sweatshop working conditions in the literature of Jewish labor poetry and song.

Unfortunately, they sang only the refrain (“Dortn iz main rue platz”—“There is my resting place”) in Yiddish—the language of East European Jews; all the verses were sung in English. However my problem is not with their performance but their introduction, as if it weren’t enough to think of the song for what it is—an eloquent, heartbreaking tale of ghetto factory life in America in the 1890s—in which “the Golden Land” of immigrants’ dreams is counter-posed against the dreary reality of their backbreaking enslavement to the chains of sweatshop machines. It was published in 1898 in Rosenfeld’s Songs of the Ghetto, translated by Leo Weiner. Cathy and Marcy evidently thought the song couldn’t stand on its own merits as a portrait of the oppressive conditions its own author labored under when he wrote the poems that earned him the title of Sweatshop Poet.

They introduced it as having been written in 1911 in response to the Triangle Factory Fire on March 25, 1911—the Centennial for which was well documented in 2011. 146 mostly young immigrant girls lost their lives under horrific conditions, including being smothered in stairwells and against exit doors that had been bolted shut to prevent them from taking an unscheduled break during their long work days. But what raised this workplace disaster to the stature of epic tragedy was the fact that so many of these young girls saw no way to escape from being burned alive except to jump from 8th and 9th story windows to their doom. In the aftermath of New York’s worst industrial disaster until 9/11, Morris Rosenfeld did write a requiem for the murdered victims—whose murderers the two factory owners got away with a slap on the wrist of $20 fines per victim.

But that requiem was not Main Rue Platz, which contains not one line or reference to the fire—not even a metaphor that might be said to suggest it. No, Rosenfeld’s poem of mourning and outrage left nothing to chance or the poetic imagination of his readers. It was written just four days after the fire and published on March 29th taking up the entire front page of the Jewish Daily Forward—the Jewish paper of record in NYC. Its title could not be more straightforward or less “poetic;” Triangle Fire Poem. Here are the opening lines:

Triangle Fire Poem by Morris Rosenfeld, 1911

Neither battle nor fiendish pogrom

Neither battle nor fiendish pogrom

Fill this great city with sorrow;

Nor does the earth shudder or lightening rend the heavens,

No clouds darken, no cannon’s roar shatters the air.

Only hell’s fire engulfs these slave stalls

And Mammon devours our sons and daughters.

Wrapt in scarlet flames, they drop to death from his maw

And death receives them all.

Sisters mine, oh my sisters; brethren

Hear my sorrow:

See where the dead are hidden in dark corners,

Where life is choked from those who labor.

Oh, woe is me, and woe is to the world

On this Sabbath

When an avalanche of red blood and fire

Pours forth from the god of gold on high

As now my tears stream forth unceasingly.

Damned be the rich!

Damned be the system!

Damned be the world!

There’s no mistaking that for Main Rue Platz. In the second half of the show Theo Bikel more than made up for one’s desire to hear the real thing. When he was finally introduced he simply sat down on a straight-back chair in front of a mic and—without plugging in his genuine acoustic folk guitar—the only one played the entire evening—played a brief set of songs in both Yiddish and Russian.

Then Theo called back his impromptu chorus of the best folk singers of the modern era—including the Limelighters’ Alex Hassilev whose otherwise quiet presence was strangely moving—and led them in that old warhorse of a peace and justice anthem—We Shall Overcome. To see Tom Paxton, Arlo Guthrie and Peter Yarrow standing behind him—their arms embraced like links on a chain—brought back fading memories of the grand finale at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival—where Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Peter, Paul and Mary and the Mississippi Freedom Singers stood together and sang Dylan’s Blowing In the Wind. It was a sight for sore eyes.

It also reminded me of the great story from two years later—July 25, 1965, to be exact—a date that will live in infamy to some, a date to celebrate for others—the date at the Newport Folk Festival when Dylan went electric. When Pete Seeger angrily interceded and told the sound engineers “If I had my ax I would cut the cable!” who came to Bob’s defense and said, “Pete, you above all should know you can’t stop change!”? The human rights activist and still unplugged Theodore Bikel. Talk about speaking truth to power!

We Shall Overcome could have ended the concert, but Theo had one more song in him and even though it was now 11:00pm and this homage to a great American and world artist had just passed the three hour mark, no one got up to leave.

Not the bright stars from the American folk revival of the 1960s, but this Vienna-born and Israeli-raised actor-singer from the 1950s gave the last word to Phil Ochs. With just him and his unplugged acoustic guitar, Theo paid tribute to America’s own great dissident poet/songwriter—in a hushed understated performance during which you could hear a pin drop—and sang When I’m Gone—Phil’s secular humanist hymn that says:

There’s no place in this world where I’ll belong when I’m gone

And I won’t know the right from the wrong when I’m gone

And you won’t find me singing on this song when I’m gone

So I guess I’ll have to do it while I’m here.

Bikel also changed Ochs’ ending to make it more personal; where Phil sang

So I guess I’ll have to do it

I guess I’ll have to do it

I guess I’ll have to do it while I’m here

Bikel sang,

So I guess I’ll have to do it

I promise I will do it

You know that I will do it while I’m here.

His perfectly timed pause before the final “You know that I will do it…” demonstrated Bikel the actor at work, making every line count. It has never been sung with more power—even by its author. Theo the singer, and Bikel the actor, became one.

It was breathtaking and showed more than all the well-turned compliments and heartfelt encomiums to an extraordinary career in music, stage and movies, why we were there.

At 90 years old, Theo Bikel is still a great artist. Once again, the old master had us in the palm of his hand—and after three hours plus left us standing and cheering for more. What more can one say, Theo, but thanks for the memories, L’Chaim! And Happy Birthday!

Now if the Palestinians would just shape up, and start listening to Peter, Paul and Mary.

As we left the theatre I noticed the Holocaust denier was gone; we outlasted the bastard.

Author’s note: The title Homage to Theo was suggested by W.H. Auden’s collection of poems Homage to Clio—one of the nine muses, the Muse of History.

Checkout Theodore Bikel’s website for more background information, song clips, pictures, etc.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com