HERE COMES THE KNIGHT: VAN MORRISON LIVE

Here Comes the Knight: Van Morrison Live

At the Shrine Auditorium – Friday January 15, 2016

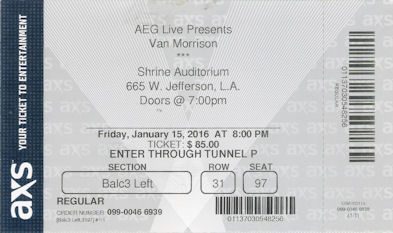

Forget about Celtic Soul, forget about Irish Mystic, forget about Belfast Cowboy, and above all forget about 1970s soft-rock—all the comfortable hybrids we’ve grown accustomed to using to describe this now-70-year old Rock and Roll Hall of Fame singer-songwriter from Northern Ireland. Last night I heard the greatest pure blues singer of my life in downtown Los Angeles at the Shrine Auditorium—L.A.’s grand dame –once luxury concert venue fallen on hard times now, viewed from the outside, until you enter and see the magnificent-layered bold Art Deco embellishments and three-story bright red upholstery-seating to the upper balconies, where I was gazing down in awe and wonder—until the lights dim, and you are transported to 1940s Chicago and a flickering marquee tells you Muddy Waters is playing tonight. Oh, he occasionally masqueraded as headliner Van Morrison, throwing in enough of his recognizable early hits to have the sold-out—and I mean SOLD OUT—I got the last seat in Tunnel P, row 31, seat 97—crowd dancing in the aisles. It was a trip, man, you had to be there, and I was thrilled I was.

Forget about Celtic Soul, forget about Irish Mystic, forget about Belfast Cowboy, and above all forget about 1970s soft-rock—all the comfortable hybrids we’ve grown accustomed to using to describe this now-70-year old Rock and Roll Hall of Fame singer-songwriter from Northern Ireland. Last night I heard the greatest pure blues singer of my life in downtown Los Angeles at the Shrine Auditorium—L.A.’s grand dame –once luxury concert venue fallen on hard times now, viewed from the outside, until you enter and see the magnificent-layered bold Art Deco embellishments and three-story bright red upholstery-seating to the upper balconies, where I was gazing down in awe and wonder—until the lights dim, and you are transported to 1940s Chicago and a flickering marquee tells you Muddy Waters is playing tonight. Oh, he occasionally masqueraded as headliner Van Morrison, throwing in enough of his recognizable early hits to have the sold-out—and I mean SOLD OUT—I got the last seat in Tunnel P, row 31, seat 97—crowd dancing in the aisles. It was a trip, man, you had to be there, and I was thrilled I was.

Someone should tell Bruce Springsteen that God has played a terrible trick on his E-Street Band—He took saxophonist Clarence Clemons, all right, but he didn’t put him in Heaven, he channeled him through Van the Man and kept those soaring hypnotic solos right here on earth—where Van Morrison opened the show a few minutes after 8:00pm with nothing but that glorious sax playing an extended jazz instrumental. Springsteen should report him to Local 47—the E-Street Band wants him back to fill out his contract. It was magical and transcendent and left the audience on the edge of our seats wanting more.

Someone should tell Bruce Springsteen that God has played a terrible trick on his E-Street Band—He took saxophonist Clarence Clemons, all right, but he didn’t put him in Heaven, he channeled him through Van the Man and kept those soaring hypnotic solos right here on earth—where Van Morrison opened the show a few minutes after 8:00pm with nothing but that glorious sax playing an extended jazz instrumental. Springsteen should report him to Local 47—the E-Street Band wants him back to fill out his contract. It was magical and transcendent and left the audience on the edge of our seats wanting more.

Van Morrison isn’t living in the past—where fans like me may still reside—he fronts the tightest 6-piece band in show business, keyboards, sax, electric bass, organ, guitar and drums. They do everything from the sacred to profane, from jazz to folk to rock to sublime classic pop from the great American Songbook and Hymnal. No one but Sinatra himself did Johnny Mercer’s That Old Black Magic as deeply felt—and Frank had Nelson Riddle and a whole orchestra behind him. And most surprisingly of all, Van Morrison sang the pure unadorned cornerstone of Negro Spirituals—Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child (A Long Ways From Home) with all the heart and (all right, I’ll say it) soul of the great Ethel Waters. In his voice and blues harmonica it was just magnificent and continued to hang in the air long after the last ethereal notes died away. Gershwin must have heard it like that when he was visiting southern churches to assimilate the gospel tradition for his opera Porgy and Bess—out of which came Summertime. But where did Van Morrison hear it? Probably on one of his working-class Belfast father’s classic American records of blues and jazz standards from the ’40s and ’50s, for he reportedly had the best record collection in town and Van Morrison understood their value. They became the core of his musical education. And that brings me to Ireland.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_jbKQHrdW7w

In the Centennial year of the 1916 Easter Uprising a true Irish rebel is touring the world to bring the sentiment of Auld Erin to distant outposts like the Shrine Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles. As W.B. Yeats wrote in his signature poem Easter 1916, “all is changed, changed utterly; a terrible beauty is born.” Van the Man has been a terrible beauty ever since his first album Astral Weeks put him on the map of the great ‘60s songwriters from a decade of social change unparalleled before or since. The depth of his perception and the range and power of his music did more than any other Irish songwriter to “forge in the smithy of my soul” what James Joyce called in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (also now in its Centennial year) “the uncreated conscience of my race.”

Born to Sing (No Plan B) Van Morrison called his next-to-last album, and a perfect description it was. How grateful we must be that he is still out here, carrying the mantle of what 18th century Irish poet Thomas More called this “land of song.” Has there ever been a “Minstrel Boy” so worthy of the name? His spectral presence lit up L.A.’s Shrine Auditorium with a body of song both challenging and uplifting. It wasn’t easy to get in: the first show on Saturday sold out weeks ago—and the added Friday night show was all but sold out this week. So I drove down to the box office on Thursday and found a stray ducat that hadn’t found its way to the ticket brokers.

Unfortunately, Born to Sing has already been revisited on Van’s latest album—scarily titled Duets: Re-Working the Catalogue—in which he chooses sixteen of his lesser known recordings (not all of which are originals) for the last stop along a rock singer’s highway to hell—inviting a series of big names to buff up their greatest hits collection. Fortunately Van avoids this pitfall and makes an earnest attempt to find different meanings in the same old songs. The album has earned excellent reviews. He has always had a love for American soul music and the blues, and here he has soul great Mavis Staples joining him right out of the box on If I Ever Needed Someone and modern blues master Taj Mahal closing the album with him on a depression era classic (once recorded beautifully by Ry Cooder as well) How Can a Poor Man (Stand Such Times and Live).

I started listening to Van when he was still a part of Them—the great Irish rock band he founded in the mid-sixties; he moved from their signature hits Gloria and Here Comes The Night to his first solo hit Brown-Eyed Girl, which still plays over the intercom at every thrift shop I’ve been in recently—one of those perfect records that (made from the 22nd studio take) announces itself with the first four guitar notes—like Beethoven’s 5th Symphony. But then Van Morrison’s life took a turn toward the depths of human sorrow—and he followed its demands with the most agonizing song about TB ever written—not even excepting the great Jimmie Rodgers TB Blues—TB Sheets. Aside from the perennial Madame George that’s the standout track from Astral Weeks—the song that raised the price of rock lyrics out of the ‘50s cellar and put them on the map of Blakean poetry. From there I listened to everything Van the Man put out—from Crazy Love to St. Dominic’s Preview to Tupelo Honey:

They can’t stop us

On the road to freedom

They can’t stop us

For our eyes can see

Men with insight

Men like granite

Knights of armor

Bent on chivalry.

Somehow in the midst of a tender love song Van finds time to take it to a higher level—the road to freedom and knights of armor—welding the personal to the political throughout. But underneath it all, like Dylan Thomas, he sings for the lovers, “who pay no praise or wages, nor heed my craft or art.”

“I used to dance to him with Johnny Limmerman, the boy down the street,” Dr.Kate Laska just told me. “You just have to listen to a few notes—he’s one of those iconic singers—one of the staples. Van Morrison takes us all back. He came out in my time when I knew nothing about how hard life could be. His music reminds me that life would turn out good; we had hope then; now in our late 60s and 70s some of our dreams have been met, or over met; but he is still there to take us back to those early dreams.”

Who else would write a song about Alan Watts—Zen Buddhist philosopher who lived on a Sausalito houseboat and wrote books on The Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are? From across two continents Watts spoke to this Irish poet with a guitar, and Morrison would give his roughhewn Zen antidotes to modern materialism back to us in song: “Oh don’t it get you/Get you in your throat/Feel the breezes blowing/All around your coat/Oh Don’t it get you/When you got to roam/Here the children calling/”Daddy’s coming home.”/Going down to Oh O Woodstock/Feel the cool night breeze/Going down to Oh O Woodstock/Going down to give my child a squeeze.”

Wilmington Morning Star – Thursday, December 17, 1998.

He found his songs in the oddest places—from Woodstock to Venice, from Canada to Belfast—reassuring us that

We were born before the wind

Also younger than the sun

As we sailed into the Mystic

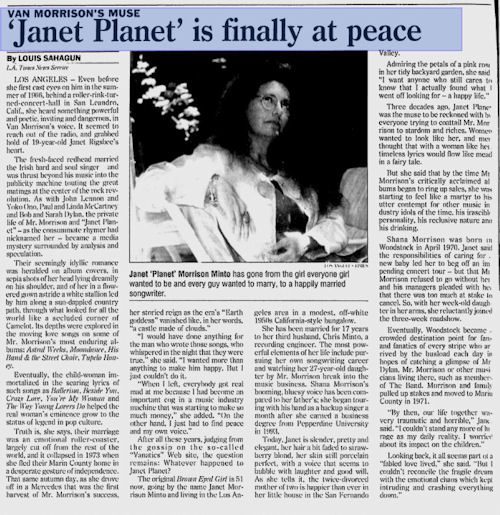

—which for Van Morrison was a real place—Mystic Seaport, Connecticut. His muse’s very name transcended time and place—Janet Planet:

Oh, the water

Oh, the water

Oh, the water

Let it run all over me.

Like Blake, he gave us the world in a grain of sand. And here he was, closing the show with it—sailing us into the mystic at the end of one more journey on the stage of L.A.’s grandest grand concert hall.

Well it’s a marvelous night for a Moondance

With the stars up above in your eyes

A fantabulous night to make romance

The 70 year-old troubadour was knighted last year—with an OMBE—Order of Merit of the British Empire—so he is now Sir Van the Man. Regardless, it was clear from first notes to last that the royal accolades have not gone to his head. The audience embraced him like a returning hero as soon as the loudspeaker proclaimed, “Ladies and Gentlemen, Van Morrison!” That’s all we had to hear and we were on our feet. Two hours later we were still uplifted and filled with joy for music that had no agenda but to convey the deepest sense of reverence for life and love. Thank you Van, for giving us your very best.

Ross Altman will be performing in the Voice In the Well Production of Chimes of Freedom Flashing along with mostly spoken word artists Sunday March 20, 2016 from 5:00pm to 7:00pm; $10 at Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center, 681 Venice Blvd, Venice, CA 90291 310-822-3006.

Los Angeles folksinger and Local 47 member Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com