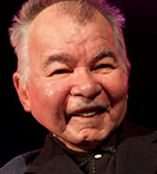

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, JOHN PRINE

Happy Birthday, John Prine:

Prine Time at the Greek – October 5, 2014

John Prine beat cancer—twice—so it was especially meaningful to hear when halfway through his sold-out show at the Greek Theatre last Sunday night a fan screamed out “Happy Birthday, John!!!” He piped back, “Not quite yet, but thanks.” John Prine was born October 10, 1946, just two months less a day before me in fact—and judging from his two bouts with cancer—squamous cell cancer in 1998 that cost him a part of his neck, cheek bone and some high notes—and an unrelated lung cancer last year—that cost him some cancelled bookings—he must feel lucky to be celebrating his 68th birthday at all.

John Prine beat cancer—twice—so it was especially meaningful to hear when halfway through his sold-out show at the Greek Theatre last Sunday night a fan screamed out “Happy Birthday, John!!!” He piped back, “Not quite yet, but thanks.” John Prine was born October 10, 1946, just two months less a day before me in fact—and judging from his two bouts with cancer—squamous cell cancer in 1998 that cost him a part of his neck, cheek bone and some high notes—and an unrelated lung cancer last year—that cost him some cancelled bookings—he must feel lucky to be celebrating his 68th birthday at all.

You’d never know it, however, from the powerful, high energy folk blues tunes he worked in between his signature laconic Midwest story songs of ordinary people caught between hope and history—the poetry of everyday life’s unsung heroes he has chronicled with more insight and empathy than any American songwriter of the past forty years.

His newly formed gravelly voice has given those songs a depth of soul and common man compassion that reaches straight into your heart and mind with truths based on his careful delineation of the minute facts of his unforgettable characters—like Donald and Lydia who “make love from ten miles away,” Sam Stone, the Vietnam veteran who succumbed to drug addiction after returning from Vietnam, and the “hollow ancient eyes” he notices in his early aching masterpiece, Hello In There, which Rolling Stone ranked #8 in the all-time saddest songs ever written. These are the “lives of quiet desperation” that America’s greatest naturalist writer, H.D. Thoreau chronicled a hundred and sixty years ago. Thoreau and Prine share attentiveness to the minute facts of human existence that transformed a small nondescript pond into a universal symbol of natural wonder (Walden) and one strip-mined Kentucky coal-mining town into Paradise Lost (Paradise).

On March 9, 2005, John Prine became the first singer-songwriter invited by America’s Poet Laureate James Kooser to read and perform at the Library of Congress. They shared the stage in a 90 minute conversation with performance about the craft of poetry and song. That’s a long ways from the Chicago folk scene that launched Prine’s career in 1970, when Kris Kristofferson heard him perform at an open mic on Armitage St. and recognized something very special in his acutely observed human portraits of the invisible men and women most of us wouldn’t give a second glance to. In Prine’s hands they became profiles in courage. Kristofferson got him a record deal with Atlantic Records and Prine’s first eponymous album came out in 1971.

The Chicago folk scene of the 1970s was the Midwest version of what Greenwich Village, Cambridge and Los Angeles were to the folk revival of the 1960s. Out of Greenwich Village came Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton and Dave Van Ronk; out of Cambridge came Joan Baez, Tom Rush, Mark Spoelstra and Jim Kweskin’s Jug Band; out of LA’s The Ash Grove came Ry Cooder and Steve Mann and out of Chicago came Steve Goodman, John Prine and Bonnie Koloc. In previous essays I have recounted the particulars of the first three, but this is the first time I have had occasion to add Chicago to the ascension of folk music in American popular culture. An unfortunate omission, really, since that is where I moved in 1978 hoping to get a start on the same path in the same folk clubs that launched both Goodman and Prine. It didn’t quite work out as planned, as I wound up having to get a teaching job to support myself during the brutal Chicago winter. But I did develop a lifelong appreciation for folk clubs like The Earl of Old Town and Somebody Else’s Troubles where Goodman and Prine got their start. I also learned that Prine didn’t start out a fully formed folk poet from the head of Zeus. He too had to earn a living and did so as a Chicago mailman until he could quit his day job.

Those early memories still very much define the kind of songwriter Prine became—his characters have jobs—they don’t just ride trains and ramble down the highway like so many folk singer-songwriter heroes of the ‘60s. Prine’s heroes work in hardware stores, they watch TV, they have parents and grandparents (Prine’s is vividly remembered in the song Grandpa Was a Carpenter)—and they have dreams, as in the old housewife in Angel From Montgomery, with its devastating last line:

How the hell can a person go to work in the morning

And come home in the ev’ning & have nothing to say.

Again and again, they fail to achieve their dreams:

There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes

Jesus Christ died for nothing I suppose

Little pitchers have big ears, don’t stop and count the years

Sweet songs never last too long on broken radios

Sam Stone

They may lose their lives, but in Prine’s finely etched songs they never lose their dignity.

Prine lives the life he sings about; when Kristofferson gave him a helping hand at the beginning he paid it forward by introducing his friend Steve Goodman to Arlo Guthrie with the words, “Arlo, Steve has written the greatest damn train song you’re ever going to hear; you’ve got to listen to it.” It was City of New Orleans, and the rest was history. When Goodman succumbed to leukemia in 1984, Prine absorbed Goodman’s web site into his own and to this day you can order all of Goodman’s albums through JohnPrine.net and Oh Boy Records, Prine’s own label that pays tribute to an early influence, Buddy Holly. He even ended one of his concert songs with a quick but indelible guitar riff straight from Not Fade Away—in which Holly in turn paid tribute to Bo Diddley’s signature beat.

His most recent album is called The Singing Mailman Delivers—a compilation of studio and live performances going all the way back to Chicago. Another great American poet started out as a mailman—Charles Bukowski—and it is almost a metaphor for the ancient idea of poetry being like a letter sent—Ezra Pound defined it as “news that stays news.” Prine delivered the goods at the Greek, with a glorious performance that captured both his quiet meditative melancholy tales of loss and his wonderful sense of humor and wit that redeemed them from depression.

Prine alternates between two main instruments that range from precise and sparkling fingerstyle on his 1968 Martin D-28 to folk-rock flat-picking on his vintage blond Gibson J-200—with a great band behind him with Jason Wilber on acoustic and electric guitar, Dave Jacques on upright bass and Pat McLaughlin on a time-traveled Gibson mandolin. And he creates some standout moments in the concert when the band takes a break and he stands there all alone at center stage—just a man and his guitar and a song-bag that will break your heart (as it broke my friend Jill Fenniger’s on Hello In There) and give you strength for the journey (on That’s the Way the World Goes Round and Crazy as a Loon—complete with sound effects of a loon gurgling). His love songs are simple and straightforward as can be: Baby, Spend the Night With Me and comforting in Don’t Let Your Baby Down.

Who but John Prine would put out an album called Standard Songs for Average People—which he recorded with country old-timer Mac Wiseman a few years back, or Fair and Square—which won the Grammy for Contemporary Folk? John Prine is the Voice of America—at our heartland best, someone who has kept his ear to the ground and in whose songs you can hear Aaron Copeland’s Fanfare for the Common Man.

When it looked like the concert might be over I turned to Jill and said, “No way he gets out of here without singing Paradise,” perhaps his best claim to having written a folk song. He came back to a thunderous standing ovation beneath an almost full moon and called popular co-headliner Conor Oberst up on stage to share the encore. It was all-acoustic and All-American as the soon-to-be 68 year-old John Prine started playing the familiar opening lines in plain D on his D-28:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EapzV7q91Fg

When I was a child my family would travel

Down to Western Kentucky where my parents were born

And there’s a backwoods old town that’s often remembered

So many times that my memories are worn.

Prine gave the great lines in the third verse to Oberst, who raged against the machine as he sang:

Then the coal company came with the world’s largest shovel

And they tortured the timber & stripped all the land

Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken

Then they wrote it all down to the progress of man.

It was a great performance.

Out in the audience, all around us, we could hear everyone singing the chorus:

And Daddy won’t you take me back to Muhlenberg County

Down by the Green River where Paradise lay?

Well I’m sorry my son, but you’re too late in asking

Mr. Peabody’s coal train has hauled it away.

As Carl Sandburg said of the Weavers, when I hear America singing, John Prine is there. Happy Birthday, John; Oh Boy!

John Prine performs with Iris Dement, Saturday, December 6, 8:00pm, Pearl Concert Theater 4321 West Flamingo Road, Las Vegas, NV 89103 702- 944-3200.

Ross Altman performs Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl Ballads in Steinbeck Calling, Thursday Oct 30, 8:00pm at Kaitlin & Erica’s Gallery

Count me among those who support the Nederlander Concerts bid to continue managing the Greek Theatre for LA Parks and Recreation; a family-owned business who has done an excellent job putting artists and fans first; the multinational corporation LiveNation is trying to muscle in and take over the Greek. For more info see WeAreTheGreek.com

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com