Glen Campbell: True Grit

Glen Campbell: True Grit

Live at Club Nokia—October 6, 2011

When Ronald Reagan announced that he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s he released a famous handwritten letter to the public, and then rode off into the sunset. Nancy became his public face and voice as they ventured into what their daughter Patty Davis called the long goodbye.

When Ronald Reagan announced that he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s he released a famous handwritten letter to the public, and then rode off into the sunset. Nancy became his public face and voice as they ventured into what their daughter Patty Davis called the long goodbye.

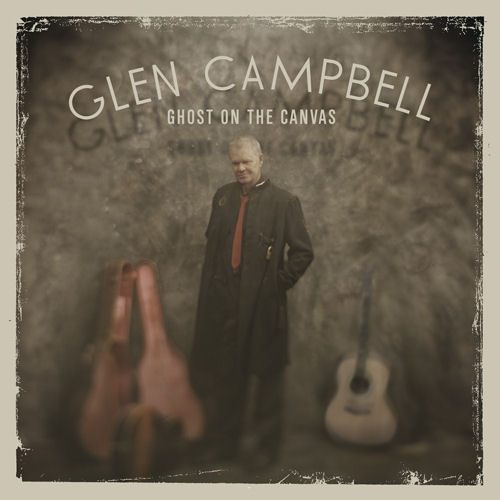

Glen Campbell has made a similar announcement, but John Wayne’s sidekick from True Grit is embarking on a goodbye tour around the track before he takes another look at the sun going down. He was at Club Nokia last night featuring songs from his legendary catalog of hits as well as his new and final studio album Ghost On the Canvas.

In the movie, you will recall, after a long, disgruntled turn as the Duke’s comic foil of a Texas Ranger, Campbell finally wins his spurs by saving Wayne’s life, not once but twice, and the second time, as Wayne pointedly and somberly observes, “after he was dead.” It turns out that Rooster Cogburn is not the only cowboy with true grit; Glen Campbell is made of the same stuff.

When Wayne and Kim Darby as Mattie Ross are in desperate straits and La Boeuf finally appears, Wayne asks him, “Where’s a Texas Ranger when you need him? We thought you was dead.” To which the fatally wounded Campbell replies, “I ain’t dead yet, you old bushwhacker,” and proceeds to pull them out of the snake pit they’re trapped in.

That was Glen Campbell last night, letting his sold out, supportive and fiercely loyal audience know that he ain’t dead yet, despite his publicly announced diagnosis of Alzheimer’s.

With the occasional lapses in memory, including being foiled by his teleprompter during a game performance of Chris Gantry’s Dreams of the Everyday Housewife, Glen Campbell put on a great show, an inspiring and uplifting concert that time and again soared to musical heights one rarely encounters on either the folk or pop music scene.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l4mylwPMPhM

Campbell can play rings around most guitarists I have long admired. He is simply one of America’s great guitarists, in the company of—as LA Times reviewer Randall Roberts noted—Chet Atkins and Merle Travis. Campbell first came to prominence as a studio session musician in the folk rock renaissance of the 1960s, and then went on to enduring success as a solo recording artist in the 1970s, relying on the extraordinary outpouring of great songs created for him by songwriters Jimmy Webb (Galveston, By the Time I Get to Phoenix, Wichita Lineman and the lesser known The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress), John Hartford (Gentle On My Mind) and Larry Weiss (his signature tune, Rhinestone Cowboy) with which Campbell ended the pre-encore concert last night.

Those were to be expected, but it was the unexpected touches and flourishes that made the show so memorable. The concert opened with a prerecorded heartbreakingly deliberate overture of Woody Guthrie’s This Land Is Your Land, with all six verses—including the ones about “No Trespassing,” and the hungry standing “in the shadow of the steeple,” and “nobody living can make me turn back—cause this land was made for you and me.” Put Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen on one side of the stage, and Glen Campbell on the other side, and, trust me, the version you are going to take home with you and always remember is Glen Campbell’s. He made you feel every word that Woody wrote. Listening to it was like a séance.

Then Campbell came out from the wings to a standing ovation—before the show started. For the next hour and a half he turned LAs hot spot Club Nokia into your living room for an intimate evening of great music. The only thing missing was a fireplace.

He did a spot on Elvis imitation, after wistfully letting on that Elvis “should have recorded this next song,” Conway Twitty’s, It’s Only Make Believe. And the way he spoke the name “Elvis” conveyed a personal affection that made you realize he would have been a friend—and no doubt was. It was a lovely routine that brought yet another ghost to his canvas—after the ghost of Woody Guthrie in the opening.

Indeed one soon saw a stage populated with bygone figures from Country music’s heyday, quoting even Minnie “I’m so proud to be here” Pearl—and then adding, “I’m proud to be anywhere” to astute comic effect. They had to share the stage, however, with Campbell’s own children who made up half of the band members on stage—banjo player Ashley, guitarist Shannon and drummer Cal Campbell. Glen’s musical director of 30 years standing T.J. Kuenster held down the keyboards.

Certainly the virtuoso tour de force of the evening was Ashley (on banjo) and Glen’s (on his dynamite electric 12-string) version of Eric Weissberg’s Dueling Banjos. When Ashley kidded him during the introduction to the instrumental that “he better be good,” Glen replied, “Hey—I’ve still got a few licks left.” And did he ever—it was jaw-droppingly brilliant, throwing down the gauntlet to Earl Scruggs, who rolls into town next month (see my accompanying preview of Scruggs’ show).

He even confronted his former demons on stage, offering the observation, “I could not hold my liquor,” a reference to his 2003 drunk-driving conviction, and adding how grateful he was to have finally gotten a handle on it. A Better Place, the opening song he and Julian Raymond wrote for his extraordinary new album, addresses his human frailty: “I’ve tried and I’ve failed, Lord…” despite which “the world’s been good to me.”

Here in concert he saved the song for his final encore, and delivered the coup de grace to an evening that demonstrated the truth of Conrad Aiken’s poem Music I Heard With You Was More Than Music. Standing next to me throughout the concert was a middle-aged couple who held each other tenderly and transparently relived many old memories held firmly in place by each Glen Campbell song now heard live most likely for the last time. The man turned to me at the end, and nodding towards my notebook filled with quick notes of song titles and phrases, asked if I was reviewing the concert. “Oh yes, I replied; I write for FolkWorks—www.folkworks.org” He made a mental note to read it later—which I hope he does.

The only visual stagecraft came after he had done a compendium of his greatest hits, when a brief but haunting almost graveyard light show prepared us for the brilliant image of Paul Westerberg’s new title song:

I know a place between

I know a place between

Life and death for you and me

Best take hold on the threshold

Of eternity

And see the ghost on the canvas

People don’t see us

Ghost on the canvas

People don’t know

When they’re looking at soul.

The most remarkable moment of the concert for me was also the most disturbing reminder of the difficult struggle that lies ahead for Glen Campbell and his family: the melodrama of trying to get through Dreams of the Everyday Housewife which called attention to the teleprompter at his feet. Even having the words in bold out in front of him was not enough to keep from losing his place—until in frustration he seemed about to scrap it in mid-performance with the comment, “Oh, it’s just an old song.” Then, almost miraculously this old trooper reached back into his song-bag, closed his eyes to the screen in front of him, let his fingers remember what his mind no longer could recall, and pulled the ending out from his Fender Stratocaster like a rabbit from the hat. That took true grit, and he fittingly followed it with the title song he sang for the movie.

On the way out of the show I overheard a brief conversation about how music is stored in a part of the brain that is not affected by Alzheimer’s. My experience singing at a number of locked facilities for Alzheimer’s patients seems to confirm this, at least up to a point. Musical memories are amongst the strongest we have, as many times I have found that people will remember old songs long after they have forgotten much else. Their short- term memory may be almost gone, and even their long-term memory problematic, but songs seem to be untouched. Add to that the mysterious and powerful motor memory that guides the sure hands of a master guitarist and one can appreciate the heroism at the heart of his goodbye tour. For Glen Campbell is saying goodbye to himself as well as to us.

Like Minnie Pearl, I was proud to be there.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com Ross’s mother Rose Altman died of Alzheimer’s July 8, 2008. This review is dedicated to her memory.

My Folkworks colleague, Terry Roland (with whom I saw the concert) wrote an outstanding review of Glen’s new album for No Depression—here’s the link.

On Sunday, October 9 at the Lobero Theatre in Santa Barbara Glen Campbell will do a benefit concert for California’s Central Coast Alzheimer’s Association. His extensive tour then takes him to England, Scotland and Ireland, before bringing it all back home to the US and the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. You can see all the tour dates on his website. He’s all in.