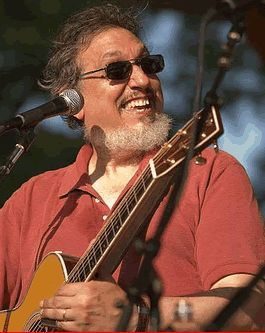

David Bromberg

David Bromberg:

Who Put the Jangle in Mr. Bojangles?

In Concert at McCabe’s March 16, 2014

There are guitarists, and then there are guitarists. And then there is David Bromberg, the guitarist who put the jangle in Mr. Bojangles, Jerry Jeff Walker’s hit song about Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, the legendary African-American tap dancer who was for black America what Fred Astaire was to white America—the standard against which all others would be judged. But before you even heard Jerry Jeff’s voice on his signature recording, you already were captured by its descending bass-line guitar intro hook—that made you see Mr. Bojangles descending a staircase—as he did in one of his famous dance routines. It was musical magic at its finest—and the guitarist who came up with it was David Bromberg.

There are guitarists, and then there are guitarists. And then there is David Bromberg, the guitarist who put the jangle in Mr. Bojangles, Jerry Jeff Walker’s hit song about Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, the legendary African-American tap dancer who was for black America what Fred Astaire was to white America—the standard against which all others would be judged. But before you even heard Jerry Jeff’s voice on his signature recording, you already were captured by its descending bass-line guitar intro hook—that made you see Mr. Bojangles descending a staircase—as he did in one of his famous dance routines. It was musical magic at its finest—and the guitarist who came up with it was David Bromberg.

To see him live at McCabe’s last night was pure acoustic artistry that comes along about as often as that great dancer—once in a generation—if you’re lucky.

We were lucky to hear him—solo (for the most part) acoustic—just Bromberg and his orchestral vintage Martin D-28 sitting on stage in front of McCabe’s legendary microphone—where so many great musicians have now stood—and none greater than David Bromberg; if you love folk music, Bromberg is as good as it gets. And it is truly a rare pleasure to get to hear him solo; on his current tour every one of his other bookings is with his band, or at larger venues his “Big Band.” I prefer the one-man band and he gave us a very generous two and a half hour concert with one intermission, two standing ovations and three—three!—encores.

Even though Bromberg did, I won’t bury the lead or save the best till last (Mr. Bojangles, of course); I’ll tell you right up front; I thought it was about the famous black dancer who invented the term “hoofing;” but according to Bromberg, it wasn’t. Apparently, and this was news to me, every black dancer in New Orleans referred to themselves as “Mr. Bojangles,” or some variant of same, such as “Jingles.” You see, the real Mr. Bojangles was never in a drunk tank, he was not down-and-out and he therefore would have never inspired such a great song by Jerry Jeff—who really was down-and-out and did spend time in jail and really did meet the character in the song. And the dog—which of course carries the song—was also real.

There, now you know, and for me it was like finding out that Santa Claus wasn’t real, for as you can see by the opening lines of this review I have carried this particular illusion with me for as long as I’ve known the song—indeed, a part of the reason I thought Bill “Bojangles” Robinson was famous was because of the song; to find out that the song’s hero was not a famous dancer, but more like everyman—opened my eyes to the secret of its appeal—going all the way back to Aaron Copeland’s Fanfare for the Common Man—in a democratic society the common man (and woman) is the hero—and the aim of the folk singer is to tell their stories—not the lords and ladies of privilege who populate so many British folk songs which emanate from a monarchical, class society. This distinction never became clear to me until David Bromberg disabused me of the notion that Jerry Jeff Walker had written a great ballad about a famous artist; on the contrary, his song is great precisely because he told the story of a Nobody—and for the first time made him a hero.

That is what David Bromberg’s exquisite guitar accompaniment captures so well—including an augmented chord right under the title at the beginning of the chorus to set it off from the rest of the song. It was made on the fifth fret (with the capo on the second fret, playing “C” in the key of “D”) and I will spend a good long time searching for it. It was the strangest chord I heard all evening—and hearing it was like standing on a mountain top and seeing the Promised Land below. In a word, it was thrilling.

Now, for the rest of the concert; if you have never heard David Bromberg live before you have missed one of the great entertainers of our time—he can be funny (and I mean Arlo Guthrie funny) in an outlandish tale of a rejected lover being asked to take his ex back—I’ll Take You Back—from his new album Only Slightly Mad, a perfect description of the artist from what he quite accurately describes as “an old English drinking song I just wrote” (and which he brilliantly got English folkies John Roberts and Tony Barrand to record with him. He can be uplifting and illuminating as in his perfectly realized version of Just a Closer Walk With Thee, complete with a revealing introduction about how thanks to his guitar mentor The Reverend Gary Davis “this Jewish kid has spent a great deal of time in black churches,” in which he told us he always felt beloved and completely accepted even though his was often “the only white face there,” and which he heartily recommended to expand your horizons and enrich your soul. No preacher or devout Christian could have been disappointed by his profoundly sincere love song to Jesus. It was also—as were many of his guitar arrangements—love songs to Rev. Gary Davis, Harlem’s most sought after guitar teacher who influenced an entire generation of performers reviewed in these pages—most notably John Hammond, Roy Book Binder and Stefan Grossman as well as one who slipped the riggings before I could get to him, Dave Van Ronk.

But Bromberg was more than just the Reverend’s guitar student and protégé; he was, as he so evocatively put it, “his seeing-eye dog.” For several years he led the master around NYC, in the same way that Josh White and Leadbelly used to lead Blind Lemon Jefferson around Dallas, Texas. Indeed, it was that relationship that led to one of Leadbelly’s great songs and 12-string guitar arrangements—Blind Lemon (“Now this is Blind Lemon—he was a blind man and I used to lead him around—him and I would go into a railroad depot/We’d sit down and talk to one another”.) And since Blind Lemon was no longer there, Leadbelly’s 12-String Stella would do the talking, as he played

Silver City Bound

Silver City Bound

me and Blind Lemon

Gonna ride on down.

In David Bromberg’s hands and guitar the entire story of the blues comes alive; they are not just songs, but chapters of the American story in black and white. Indeed, Bromberg is so well aware of the blues influence on his own generation of white performers, he did not even bother singing one of Robert Johnson’s—King of the Delta Blues—songs (“because everyone does them,”) so he regaled us with an equally haunting and less-travelled song of fellow blues guitarists Leroy Carr and Scrapper Blackwell—Midnight Hour Blues. The title says it all.

Dear Reader, I must take a break from this review, for it is St. Patrick’s Day and your intrepid reporter has a booking to sing Irish songs at a retirement home in Sherman Oaks; it’s high noon and high time to get on the road; we’ll come back to Bromberg this evening. I promise.

Well, here we are again; after putting on my Irish fisherman’s cap for a musical trip to the Emerald Isle (with help from the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem and a few sentimental favorites from Van Morrison, Burl Ives and John McCormack I am back in my garret reflecting on the Delta blues and ragtime classics like Scott Joplin’s Maple Leaf Rag performed by David Bromberg as learned from Harlem’s blind Reverend Gary Davis—it’s almost as big a jolt as the 4.4 temblor that shook me out of bed at 6:30 this morning—epicenter in Encino, which was close enough thank you. Bromberg said he likes to transcribe piano pieces for the guitar, and performed a second guitar shaker he adapted from Ray Charles A Fool for You—which he said he had never performed live before. In this case the first time was the charm because it was languorous and lovely.

Well, here we are again; after putting on my Irish fisherman’s cap for a musical trip to the Emerald Isle (with help from the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem and a few sentimental favorites from Van Morrison, Burl Ives and John McCormack I am back in my garret reflecting on the Delta blues and ragtime classics like Scott Joplin’s Maple Leaf Rag performed by David Bromberg as learned from Harlem’s blind Reverend Gary Davis—it’s almost as big a jolt as the 4.4 temblor that shook me out of bed at 6:30 this morning—epicenter in Encino, which was close enough thank you. Bromberg said he likes to transcribe piano pieces for the guitar, and performed a second guitar shaker he adapted from Ray Charles A Fool for You—which he said he had never performed live before. In this case the first time was the charm because it was languorous and lovely.

Bromberg has a lot of faith in his audience—and was not above inviting us to sing along on a couple of songs. The test of his faith, however, was that unlike Pete Seeger, who taught the audience their parts and then coached them along throughout, David Bromberg simply let the audience carry the chorus once they gave any sign of knowing it, while he bowed out and just smiled like a proud papa. And ladies and gentlemen, I’m not talking about communal songs that have made the rounds of every pop radio station and juke box in the country like If I Had a Hammer and Blowing in the Wind. Bromberg’s audience is more like a secret blues society who must have learned these songs from either live performances or the original records; here’s one they sang with down home fervor:

I like to sleep late in the morning

I don’t like to wear no shoes

Make love to the women while I’m livin’

Get drunk on a bottle of booze.

Not great poetry perhaps, but what made this song so memorable is that David Bromberg—who like Bobby Fischer knows every move in the book—seemed to get stymied in the end game and his guitar was battling him to a draw. He kept playing a slightly different figure working his way slowly up the neck trying to resolve the “C” chord pattern circle of fifths into a resolution when he suddenly confided to the audience “There used to be a way out of this,” like Wittgenstein developing a mental cramp during a particularly difficult philosophical investigation. It was pure magic—watching his fingers thinking out loud and leading us into a Zen-like trance of anticipation when—just before he slipped off the fret board entirely—he found the note he was looking for around the fifteenth fret, declared victory and got out.

He ended the first half by bringing his sometime accompanist and road manager guitarist Mike Russo to the stage and inviting him to join him on an instrumental—which as if in preparation for St. Patrick’s Day turned out to be an Irish reel—the title of which I didn’t recognize. But it was definitely a tour de force for two guitars and brought the opening set to a perfect close. Not, however, before making the best pitch for the sale of his CDs and DVDs (“and BVDS,” he added tongue-in-cheek—though with Bromberg you are never quite sure; he is, after all, “slightly mad.”) He let us know in no uncertain terms that the fate of the economy was now in our hands, and “if there is anything left tonight on my merchandise table…the terrorists win.” I knew he was a great guitarist; I knew he was a soulful singer; I had no idea he was also a storyteller with Arlo Guthrie’s sense of the absurd and U. Utah Phillips perfect timing—who held nothing back.

Let it be said that the terrorists did not win tonight; the crowd in front of McCabe’s counter where Bromberg’s CDs and DVDs were set up was ten deep and not about to let any of them get away. I couldn’t even get close, which was fine with me; I have a shelf-full of his original LPs—made when he was still a skinny kid with a scraggly beard and wire-rim glasses backing up Bob Dylan and the Band at the Isle of Wight in 1970, where he graduated from Columbia University to Columbia Records when a Columbia A-and-R talent scout heard this funny-looking side man and thought, “He’s as good as the guys on center stage,” and signed him on the spot. Forty years later, and next to John Hammond, that was the best A-and-R man Columbia ever had. David Bromberg was a keeper.

But he was also still a seeker, whose musical journey hit a temporary roadblock in 1980. He dissolved his band, moved from New York City to Chicago and took up violin-making. He and his wife Nancy then tired of one-too-many Chicago winters (I went through them from 1978 to 1980, as recounted in my last two columns, and I know what he means) and they moved to Wilmington, Delaware, where they set up shop as David Bromberg Fine Violins. Not until 2002, twenty-two years later did Bromberg hear the road calling again, and this time he returned to performing and recording for good.

He is a master of a multitude of American musical forms, not just the blues and ragtime, but bluegrass and folk (he played Woody Guthrie’s version of 900 Miles on his mandolin for an encore), country, gospel and jazz as well. A David Bromberg concert is therefore a tour of America through its great musical traditions, held together through a unifying sensibility of excellence and admiration for the trailblazers whose lamp he now keeps trimmed and burning.

The stories he tells behind every song are an integral part of his stage magic; to take but one example: how many times have you heard someone sing Delia’s Gone (recorded by Johnny Cash among many others), or the lesser known variant Delia (recorded by Bob Dylan and David Bromberg) without ever knowing who Delia was, or if she was indeed anybody. You don’t get away from a Bromberg concert without learning that she was a real person, a fourteen year-old African-American prostitute named Delia Green who was murdered by a lover around 1900 in Savannah, Georgia, and whose murder—despite her lowly station in society—was condemned by everybody in town from the pimps to the Chief of Police who caught him and the judge who put her murderer away for life. (He wound up serving 13 years.) In Bromberg’s matchless telling the clear implication is that she won the sympathy of the whole town because people in all walks of life retained her services—not just the stereotypical Johns, but the higher-ups as well. It almost makes you think of the former Attorney General of New York who was caught with his hands in the cookie jar, so to speak. Almost? Not by a damned-sight. Delia has lasted because she is archetypal, just like Mr. Bojangles represents every down-at-the-heels starving artist—Everyman—Delia is Everywoman.

But to fully appreciate the power of the song, you need to know that she was also this woman—that like Sarah in The Hustler she lived and she died. That’s what David Bromberg brings to his craft—an unending curiosity about the lives he sings about. They are clearly more than songs to him. Each is a compelling portrait of a real human being, and Bromberg reaches deep inside of himself and them and unfolds their story leaf by leaf, to make them live again.

This is folk music with a beating heart, and when Bromberg left the stage at the end he bowed and said, “Thank you; it has truly been a pleasure playing for you tonight.”

To which one can only add, “Thank you, David; it was truly a pleasure listening to you.”

David Bromberg performed at McCabe’s Concert Series with thanks to Lincoln Meyerson/

David Bromberg Concert annotated setlist by Ross Altman

1st Set

1) Hard Work John (flatpicked)

2) One Sided Love (If the Rabbit Had a Gun)(fingerpicked)

3) Hard Is the Fortune of All Womankind (a capella)

4) I’m a Rambler, I’m a Gambler (key of “A” fingerpicked)

5) Midnight Hour Blues (key of “A”)

6) I Like to Sleep Late In the Morning (“C” blues)

7) The Strongest Man Alive (Bromberg’s “Old English Drinking Song I wrote” source of album title “Only Slightly Mad”)

8) Let the High Times Roll (“C”)

9) I Ain’t Goin’ Down That Big Road All By Myself (“E”)

10) Irish Reel (with Mike Russo, 2nd Guitar flatpicked)

2nd Set

11) I’ll Take You Back (“E” comic masterpiece on Only Slightly Mad—“I’ll take you back when rattlesnakes have knees/When money grows on trees/When rats learn how to fly/And winos don’t get high/When James Brown can’t get funky/And King Kong ain’t a monkey/I’ll take you back/When they find weapons of mass destruction in Iraq”—you get the idea)

12) Don’t the Road Look Rough and Rocky (“G”flatpicked; guest Brantley Kearns sang harmony)

13) A Fool For You

14) Just a Closer Walk With Thee (“A”)

15) Maple Leaf Rag

16) Wild About My Loving (“I ain’t no lawyer/Ain’t no lawyer’s son/But I can get you off/Until

your lawyer comes”—you get the idea)

17) Wooly, Wooly (“A” audience raised the roof on the chorus as Bromberg turned folk into rock and back into folk)

18) Delia (drop “D” tuning for first and only time, fingerpicked, as were most songs unless otherwise noted)

19) Bring It On Home to Me by Sam Cooke, 1962 (“G” DB turned this into a tragic-comic cante-fable about his own mistakes as a husband, poking fun at himself)

Encores

20) 900 Miles (on mandolin)

21) Long Way to Nashville by Paul Seibel)

22) Mr. Bojangles by Jerry Jeff Walker (2nd fret capo play “C”)

David Bromberg Discography

* David Bromberg (1972)

* Demon in Disguise (1972)

* Wanted Dead or Alive (1974)

* Midnight on the Water (1975)

* How Late'll Ya Play 'Til? (1976)

* Reckless Abandon (1977)

* Out of the Blues: The Best of David Bromberg (1977)

* Bandit in a Bathing Suit (1978)

* My Own House (1978)

* You Should See the Rest of the Band (1980)

* Long Way from Here (1987)

* Sideman Serenade (1989)

* The Player: A Retrospective (1998)

* Try Me One More Time (2007)

* Live: New York City 1982 (2008)

* Use Me (2011)

* Only Slightly Mad (2013)

Ross Altman, Len Chandler, Peter Alsop and others will play in the Ash Grove Music Memorial Concert for Pete Seeger at the First Unitarian Church, Saturday, April 5, from 2:00 to 5:00pm; 2936 W. 8th St., LA, CA 90005; $20; 213-389-1356, produced by Ed Pearl as a benefit for the First Unitarian Church, where Seeger played when he was blacklisted.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com