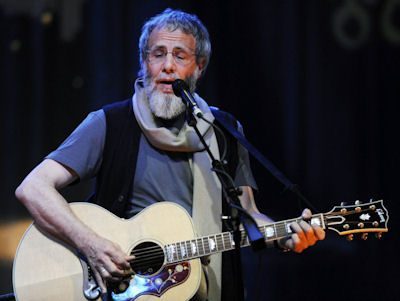

CAT STEVENS-YUSUF IN CONCERT

Cat Stevens-Yusuf in Concert

No Sex, No Drugs, No Rock and Roll—Got Folk?

At The Nokia Theatre—LA Live – December 14, 2014

England’s greatest mathematician, pacifist and philanderer once said of Austria’s greatest logician and language philosopher: “Ludwig Wittgenstein came to Cambridge and taught the English to speak their own language.” Bertrand Russell, meet Cat Stevens. With his new album Tell ‘Em I’m Gone—from the Lead Belly chain gang song Take This Hammer—English folk singer Cat Stevens has come to the U.S. and taught Americans to sing our own folk songs—black, blues, and even the singing cowboy Gene Autry classic (written by former Louisiana Governor Jimmy Davis) You Are My Sunshine, a song relegated to nursing home sing along song sheets until Cat reshaped it into a modern blues and made it shine all over again—as he did with Lead Belly.

England’s greatest mathematician, pacifist and philanderer once said of Austria’s greatest logician and language philosopher: “Ludwig Wittgenstein came to Cambridge and taught the English to speak their own language.” Bertrand Russell, meet Cat Stevens. With his new album Tell ‘Em I’m Gone—from the Lead Belly chain gang song Take This Hammer—English folk singer Cat Stevens has come to the U.S. and taught Americans to sing our own folk songs—black, blues, and even the singing cowboy Gene Autry classic (written by former Louisiana Governor Jimmy Davis) You Are My Sunshine, a song relegated to nursing home sing along song sheets until Cat reshaped it into a modern blues and made it shine all over again—as he did with Lead Belly.

Peace Train roared into LA for the last stop on his first tour in 35 years and I was there. It was a marvel of great folk music, great theatre, a great band, and a great entertainer at the top of his game. It was hands down the best concert I have seen this year; Yusuf Islam—the Artist Formerly Known as Cat Stevens—saved the best till last—in every sense of the word. But the final encore we’ll get to later.

Let’s start with the tickets: there weren’t any; at least not the kind you can take with you and show at the door to see Cat Stevens—the name on the marquee despite his well-publicized name change and religious conversion from thirty-five years ago that led him to walk away from one of the most successful careers in music history and devote his life to his new faith and family. When he was inducted (by Art Garfunkel) into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this past year he made a point of saying that they must have made a mistake: “You have admitted to this hall a man who doesn’t do drugs, sex or rock and roll and sleeps only with his own wife. What happened?” Then he brought down the house with three of his favorite songs that have become a part of the DNA of modern song: Moonshadow (in Sing Out!’s Bible of modern folk song Rise Up Singing), Wild World and Peace Train. That’s why he was there: for thirty-five years—from only radio air play, songbooks and record sales we couldn’t get them and a dozen other songs out of our head. They were as permanent as the Beatles, Bob Dylan, or Woody Guthrie. They were the songs we marched to, dreamed to, fell in love to and even broke up to—the soundtrack of our lives.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ekiAhrlh5FE

But where were the tickets? Cat Stevens—or Yusuf—they were both printed on the Peace Train T-shirts he had for sale in the lobby—along with his new CD—the first in 35 years—aptly named Tell ‘Em I’m Gone. He is no longer running from his past; so call him what you want to—he was born in Marylebone, England and his Greek birth name was neither: Steven Demetre Georgiou; 21 July 1948. For simplicity’s sake I’ll just call him Cat or Yusuf; he single-handedly managed to defeat the scalpers who were marking up his tickets five times and more to cash in on their unprecedented demand by eliminating paper tickets altogether and limiting paperless tickets to two per household. No more could the ticket brokers buy up to eight tickets planning to use two and sell the rest. The only way you could get into the concert was by showing your credit or debit card used to purchase the tickets and a valid picture ID. It was harder to get into the Cat Stevens concert than for a black person to vote in Alabama. Lenor and I had to show our IDs three times before we reached the door. It took a while to thereby process everyone’s admission: twenty minutes after the 8:00pm start time an announcer came out to inform us that they still had a thousand people outside waiting to be seated and were grateful for our patience—they wanted everyone seated before the concert started. We relaxed: after all, we had waited 35 years to hear Cat sing; what’s another ten minutes?

Photo by Lenor De Cruz.

So while we’re waiting for the concert to start, let me describe the amazing stage setting that made this an unforgettable theatrical as well as musical experience—as you looked up at the stage you saw—tricked out in every detail—a train station as the backdrop, complete with a large clock on the roof, a windmill to the left indicating it was somewhere outside of town—perhaps the desert or the prairie—and a brightly lit sign to the audience’s left pointing out the train’s destination: Los Angeles. How could you not feel right at home? Lenor and I were both enchanted by the effect of knowing we were about to go on a musical and spiritual journey even before Cat took the stage. But what train was it referring to? It turns out there were two: The Peace Train (Late Again) Tour that Cat had dubbed his comeback series of concerts that started in London at the beginning of November and was reaching its destination on its last stop in LA tonight. But there was another train running too—the Curtis Mayfield song Cat has made his own (but always crediting Mayfield as the author as Cat conscientiously does with every song he covers) People Get Ready. This train is bound for glory.

When Cat Stevens finally took the stage he got a standing ovation that went on for five minutes—until he brought down the house with, “You paid for those seats—why don’t you use them?” It was a beautiful moment—the first of many, as he engaged the audience throughout with asides and song introductions and music history anecdotes that displayed a fully present entertainer who was just as happy to be here as we were. He did a great song by Edgar Winter—Dying to Live—from his new album and in his introduction made sure we understood who had written it and how grateful he was to be able to sing it. Indeed, throughout the show Cat Stevens entire approach, choice of songs, and incidental comments made one appreciate how profoundly important the art of song was to our lives and well-being. More than any artist I have encountered he made one believe in art as a force for good in the world. He was clearly there to serve the songs, not the other way around. He also said not a word about religion; his songs spoke for him.

His innate sense of gratitude for life—as so eloquently articulated in the Edgar Winter song he made a touchstone of his show—even carried over into the extended way he introduced his band. And afterwards he also introduced the lighting designer who made that backdrop such an exquisite part of the entire show; the set designer who created it, and the sound engineer who made them all sound so great, right down to his guitar technician (Steve) who rotated his three good guitars—an acoustic-electric I couldn’t identify; his blonde Gibson J-200 and his great Martin D-28 for the quiet reflective songs that defined his appeal in the early 1970s. It was a lesson in humility that every artist of his stature should emulate but rarely do. He made us all—including the audience—feel important and essential. When he segued from the Procol Harem song The Devil Came From Kansas into the Beatles’ All You Need Is Love the whole sold-out 7,100 seat Nokia Theatre was singing along, echoing from the walls and Sistine Chapel-high ceiling in this great acoustically amazing hall–and believing in its power to change the world.

But in a sense those were the moments I would have expected at a Cat Stevens concert; what lifted this show to another level—and made it a great folk concert—were the moments and songs I didn’t expect. Who would have expected this artist to remake a favorite cover song of his—Sam Cooke’s classic Saturday Night—into a contemporary protest song about hard times. Stevens introduced it by saying that he couldn’t sing a song about “dating chicks” anymore, because he just doesn’t do it—to the palpable groans from some disappointed audience members—so Cat changed the song’s chorus from

Another Saturday night

And I ain’t got nobody

I got some money ‘cause I just got paid

to

Another Saturday night

And I ain’t got no money

I got no money ‘cause I ain’t got paid

and then the powerful portrait of the unemployed worker in a down-turned economy—as he changed the lines:

How I wish I had someone to talk to

to

How I wish I had someone to work for—I’m in an awful way.

The first verse he similarly transformed from:

Got in town a month ago

Seen a lot of girls since then…

to

Got in town a month ago

Made a lot of calls since then…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0k6mQyu2GxM

but all to no avail. It was a brilliant transformation of a golden oldie into a hard-hitting song for hard-hit people—just the kind of song Woody Guthrie or Joe Hill fashioned out of the popular songs of their time.

But even that was not the real highlight of the show for me—in terms of songs that seek to make a difference and define the art of the folk singer. He saved that for his first encore—after performing a string of his early beautiful hits like Wild World, his cautionary tale to a lover about to leave him, Where Do the Children Play, his great lament for the disappearing parks and untouched wilderness from overdevelopment, Father and Son, his life lessons song from old to young, and to me his most touching and beautiful love song, The First Cut Is the Deepest.

After he came back to a thunderous standing ovation he sat down with just his old D-28, like a folk singer from fifty years ago might have, and announced that he would sing a song he had written in memory of Nelson Mandela. Excuse me, Cat, but isn’t that subject a little above your raising—you with your soft-rock and sensitive 1970s singer-songwriter credentials firmly lodged in our collective memory. Who do you think you are? Phil Ochs? Bob Dylan? Bruce Springsteen? But it wasn’t the subject of Nelson Mandela that made this so utterly surprising—after all, this would not be the first song written in his memory. No, it was rather the historical depth that Cat Stevens/Yusuf Islam went to in order to uncover this tribute to the departed South African human rights giant of the 20th Century—the man who ended Apartheid after languishing for twenty-five years on Robben Island Prison—South Africa’s Alcatraz—without seeking vengeance against his captors.

Cat went all the way back to 1946—sixty-eight years ago (I know because that’s when I was born)—and a gold miners’ strike Mandela led that gave birth to the ANC. The song, also from his new album, was called simply Gold Digger and is a modern masterpiece. Amazing, I heard myself saying under my breath. It was a revelation, a work of historical reconstruction and memory transmuted into a great protest song.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7sjSHazjrWg

Then at last, after a brilliant and moving two-hour concert Cat finally satisfied the expectations he had built up since practically the beginning—of singing his classic peace song that gave this tour its resonant title, suggesting that we had been wrong in thinking peace was just around the corner, despite the hope offered in his and many other songwriters antiwar anthems over the past thirty-five years. It also spoke to the frustrations of his devoted fans who had been kept waiting all these years for another live show to accompany their record collections and radio exposure. Once again he strolled out from the wings with his beautiful blonde J-200 and started the magical opening chords of Peace Train. The applause was deafening. But then the set designer and lighting designer’s genius came into play as well, for as he came to the lyrics:

Oh peace train sounding louder

Glide on the peace train

Come on now peace train

Yes, peace train holy roller

Everyone jump upon the peace train

Come on now peace train

suddenly the clouds seemed to open up above the train station behind the band—and the sun poured down from the sky. It was electrifying and sublime at the same time—a perfect synergy of light and sound in a melding of word, music and stagecraft. This was nothing like the vague, impressionistic psychedelic light shows identified with so much modern folk rock performance style—this was true figurative art—done in the Depression-era Americana mural style of Thomas Hart Benton; it would not have been out of place in any major art museum in the country.

After this third great encore one would have thought the show was over—and no one least of all me would have felt short-changed. But as I said at the beginning, Cat Stevens saved the best till last and with all the available guitars his guitar tech Steve brought back the vintage Martin D-28 and Cat walked back up to the microphone. “Well, it looks like we’re going to be here till morning—to a resounding roar of approval from his appreciative fans. He quickly checked that with “I didn’t say that.” What he meant to say was “We’re going to be here till Morning—as in Morning Has Broken—his first major hit from Teaser and the Firecat, with words by Eleanor Farjeon to a Scottish Gaelic melody. It was quiet, reflective, and transcendent—one might almost say it was proof that the last cut was the deepest. Without quite knowing it, that was the song Lenor and I and everyone else in the Nokia Theatre had been waiting for. And it was worth waiting for.

When the last ethereally beautiful notes died away Cat came back to the microphone and thanked us one more time for being there: “God bless you all,” and finally, “Peace.”

Cat Stevens is back—and I know I speak for everyone in that hall in hoping that we don’t have to wait another thirty-five years before he returns. Based on Cat’s/Yusuf’s own memoir—available out in the foyer—I doubt very much it will be. It’s called Why I Still Carry a Guitar. Clearly this spiritual messenger still believes in the power of music to carry that message:

Take this hammer

Carry it to the captain

Tell ‘em I’m gone

Tell ‘em I’m gone.

Lead Belly learned it in prison—a freedom song worthy of Nelson Mandela.

Los Angeles folk singer Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com