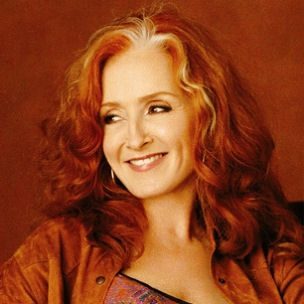

Bonnie Raitt: Laughing the Blues Away

Bonnie Raitt: Laughing the Blues Away

In Concert at Copley Symphony Hall

San Diego, California February 23, 2013

Fresh on the heels of her Grammy win for Slipstream in the Americana category Hall of Fame Folk/Blues/Rock Guitarist Singer-Songwriter Bonnie Raitt brought her airtight band, including bassist James “Hutch” Hutchinson, guitarist George Marinelli, drummer Ricky Fataar and keyboardist Mike Finnigan into San Diego’s premiere concert venue last night and tore the roof off like it was a roadside juke joint on Route 66. For two hours plus she blasted the seams off the walls with her vintage Fender Stratocaster, and then knocked your socks off with tender readings of two Bob Dylan songs on her vintage double pick-guarded Guild acoustic, playing both bottleneck slide and fingerstyle guitar. Bonnie has an impressive pedigree, her father being Broadway star John Raitt, the man who played Curly and introduced Oklahoma to the stage in 1947, two years before she was born.

Fresh on the heels of her Grammy win for Slipstream in the Americana category Hall of Fame Folk/Blues/Rock Guitarist Singer-Songwriter Bonnie Raitt brought her airtight band, including bassist James “Hutch” Hutchinson, guitarist George Marinelli, drummer Ricky Fataar and keyboardist Mike Finnigan into San Diego’s premiere concert venue last night and tore the roof off like it was a roadside juke joint on Route 66. For two hours plus she blasted the seams off the walls with her vintage Fender Stratocaster, and then knocked your socks off with tender readings of two Bob Dylan songs on her vintage double pick-guarded Guild acoustic, playing both bottleneck slide and fingerstyle guitar. Bonnie has an impressive pedigree, her father being Broadway star John Raitt, the man who played Curly and introduced Oklahoma to the stage in 1947, two years before she was born.

Bonnie Raitt knows how to reach inside your soul and comfort your afflictions, as well as to reach inside your mind and make you laugh at the human condition. England’s greatest 20th century poet W.H. Auden summed up in his ballad As I Walked Out One Evening, “you must love your crooked neighbor with your crooked heart.”

It was a difficult lesson in the blues I learned from my seatmate Jill Fenimore, the seminal American musical art form created by African-Americans and absorbed by folk, rock and jazz singers the world over. Of course you won’t find Bonnie Raitt’s records in the blues section at any local record store—that is reserved exclusively for black artists. But Bonnie Raitt is a true blues singer and guitarist. She waited until nearly the end of the show to get back to the basics from whence she came—sitting all alone on an empty stage without her band, just her incomparable voice and acoustic guitar, singing and playing her heart out on an old Chris Smither’s blues song, Love Me Like a Man.

It was both chilling and oddly comforting at the same time—to see and hear this 63-year-old consummate performer in an aural version of a vintage black and white photograph—before she added all the rock and roll bells and whistles that filled this huge hall. Bonnie Raitt’s six-string symphony was enough for Jill and me.

The funniest song of the night (based on Jill’s rollicking laughter) was reserved for her keyboardist Mike Finnigan—a Roy Alfred’s blues satire of a woman bent on cheating—I’ve Got News For You:

You said before we met

That your life was awful tame

Well, I took you to a night club

And the whole band knew your name

Oh well, baby, baby, baby

I’ve got news for you

Oh, somehow your story don’t ring true

Well, I’ve got news for you

Well, you phoned me you’d be late

‘Cause you took the wrong express

And then you walked in smiling

With your lipstick all a mess

Oh, let me say to you little mama

Wo, I’ve got news for you

Ah, your story don’t ring true lil’ girl

Yeah, I’ve got news for you, baby

Oh, you wore a diamond watch

Claimed it was from Uncle Joe

When I looked at the inscription

It said, “Love from Daddy-o”

Oh, well baby, wo lil’ girl

I wanna say I’ve got news for you

Ah, if you think that jive will do

Let me tell you, oh, I’ve got news for you

Well, somehow your story don’t ring true

Wo, I’ve got news for you, oh, oh

The most moving moment, however, was Bonnie Raitt’s magnificently soulful version of John Prine’s Angel From Mongomery, now one of her signature songs. “I am an old woman,” she began a capella, and by the end you knew she had lived every line of Prine’s song: “How the hell can a person go to work in the morning/And come home in the evening & have nothing to say.”

One of the more endearing traits of her show, in fact, is that, like Frank Sinatra, she makes a point of underscoring who wrote each of the songs in her show, both words and music. It is only when she neglects to mention it that you realize she wrote the song.

This turns on its head the introductory style of many performers I have encountered: they will make very clear that they wrote any original song in their set, while ignoring the songwriters responsible for the others. Bonnie Raitt is a class act beloved by fellow songwriters in not just name-checking their authorship, but letting her audience know how much she admires them, and even when and where the song was written.

That is how I know she opened the show with a Randall Bramblett song Used to Rule the World, which she performed on Jay Leno’s Tonight Show just a couple of nights before her soldout concert—and followed it with a Gerry Rafferty song, Right Down the Line. They also happened to open her latest album Slipstream, which just won her her fourth Grammy.

Then she got inside of two Bob Dylan songs from his comeback 1997 album Time Out of Mind, Million Miles and Standing in the Doorway and brought out every inch of heartache in their regret-filled portraits of unrequited love:

You told yourself a lie

That’s alright I told myself one too

Well I try to get closer

But I’m still a million miles from you.

Those opening lines demonstrate what separates Dylan from other songwriters—however entertaining and memorable they may be: he ignores the lies she may have told him—the focus of so many blues cheating songs—and instead zeroes in on the lies they each told themselves. That is the difference between popular music—even firstrate popular music—and poetry—a poet (like Auden, like Dylan) portrays the “crooked heart” that lies to him or herself as much as to others.

And that is Dylan’s quintessential contribution to the Blues, and what draws a performer of Bonnie Raitt’s caliber to his music, like Standing In the Doorway:

Oh I know I can’t win

But my heart it just won’t give in

I see nothin’ to be gained by any explanation

There are no words that need to be said

You left me standing in the doorway cryin’

Blues wrapped around my head.

Both of these exquisite blues tracks (produced by Joe Henry) are included in Bonnie Raitt’s Slipstream, which accounted for roughly half of her set list. She also ranged widely through her deep catalogue of earlier favorites, for she started recording in 1969, at only 20. After twenty years of struggling for commercial success she got there with her tenth studio album, released in the spring of 1989 and aptly titled Nick of Time. After her Grammy sweep in early 1990 it went to the top of the U.S. charts and Rolling Stone magazine voted it #230 in their list of 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. Perhaps even more meaningful to Bonnie Raitt—and to anyone else struggling as she did with both alcoholism and drug addiction is her description of it as “my first sober album.”

From having been observed at The Troubadour to be “drunk on her ass” (in an anecdote Jill related to me) during her drinking days to the top of the charts at the beginning of what she proudly told her audience was now her 26th year of sobriety—well that is a hard road to travel. As someone who recently entered that same program and now goes to meetings regularly, I can tell you that of all the humorous and riveting stories Bonnie Raitt told us during her concert that was the one that meant the most to me. To share her story with her fellow travelers in sober living was a great gift. Anonymous be damned. She is an inspiration who reaches back to help others on their journey.

Bonnie Raitt is also a longstanding inspiration to women—especially women guitarists like Jill Fenimore. Bonnie Raitt is number 89 in the Rolling Stone list of the 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time—and number 50 in the Rolling Stone list of the 100 Greatest Singers of All Time (source: Wikipedia)

And just as central to her work as a musician is her lifelong activism; indeed she was one of the founders of the anti-nuke movement in this country, lending her music and her voice to what became a national campaign. Even forty years later, in San Diego, organizers against the San Onofre Nuclear Power Plant were handing out leaflets at her most recent concert, knowing they would be surrounded by receptive activists. Equally moving to me though is her on-going commitment to the older black blues artists from whom she learned her craft. Here, from Wikipedia, is powerful testimony that she not only talks the talk but walks the walk.

“In 1994 at the urging of [her early mentor] writer Dick Waterman, Raitt funded the replacement of a headstone for one of her mentors, blues guitarist Fred McDowell through the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund. Raitt later financed memorial headstones in Mississippi for musicians Memphis Minnie, Sam Chatmon, and Tommy Johnson again with the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund.”

The twenty years it took her to achieve commercial popularity is reminiscent of another artist who had an exceptionally hard road to climb—that would be Robert Frost. When America’s greatest modern poet started out he told his father that he planned to be a poet—not exactly what his father wanted to hear. But he was so determined that his father insisted that at least he accept a deadline—after which he would do something sensible with his life, like be a farmer or a teacher. “All right, I’ll give you ten years,” his father offered. “Give me twenty,” replied Frost.

And exactly twenty years later—in 1913—Frost’s first book A Boy’s Will was published in England. More remarkable for the coincidence with Bonnie Raitt’s timeline is that two years later in 1915 it was first published in the U.S. Born in 1875, he was forty years old, the same age as Bonnie Raitt when she released her first commercially successful album.

24 years later she is still on the road, and in the midst now of a world tour that will have 85 concert stops along the way, including another TV appearance this Friday March 1 on the Ellen Degeneris show on NBC at 4:00pm.

It was thrilling to hear in great form, drawing from her wide emotional pallette, but even in the depths of the blues she sings with such heart, able to laugh and share her “experience, strength and hope” with her devoted audience—laughing the blues away, one day at a time.

Bravo, Bonnie!

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com

Ross Altman and Theresa Bonpane will co-host a Party/Fundraiser for John Johnson, Publisher & Editor of Change-Links Progressive Community Calendar Saturday, March 30th, 6:30 to 10:30pm at The New Peace Center, 3916 Sepulveda, Culver City 90231; $10 at the Door; RSVP to Frank Dorrel: fdorrel@sbcglobal.net – fdorrel@addictedtowar.com 310- 838-8131.

Ross Altman will host Rebels With a Cause, a tribute to Paul Robeson, who was born on April 9, 1898; Marian Anderson, who gave her historic Easter Sunday Concert in front of the Lincoln Memorial on April 9, 1939;and Phil Ochs, who took his own life on April 9, 1976, on Tuesday, April 9, 2013 at The Talking Stick Coffeehouse at 1411 Lincoln Blvd in Venice, 310-450-6052, 7:00 to 10:00pm—free and open to the public.