Bob Dylan Concert Review

Dead Sea Scrolls Live at Hollywood Bowl

Bob Dylan in Concert—October 26, 2012

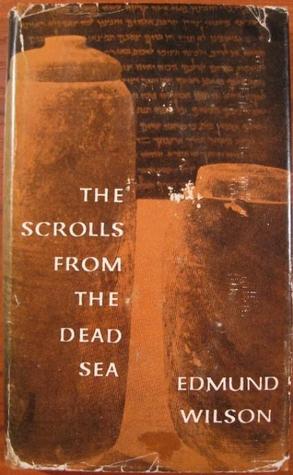

Like an Old West Preacher, Bob Dylan came to hold his semi-annual revival meeting at the Hollywood Bowl last night, with ancient texts discovered in the Near East more than half century ago. There were questions, “How many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man?” There were parables, “God said to Abraham, ‘Kill me a son;’ “Abe said, ‘Man, you must be putting me on…’” There were warnings by the side of the road: “Businessmen they drink my wine/Plowmen dig my earth/None of them along the line/Know what any of it is worth.” And there were signs indicating No Direction Home. And by the way, this Hollywood Bowl was not the one north of Franklin and Highland—it had its own address: Desolation Row.

Like an Old West Preacher, Bob Dylan came to hold his semi-annual revival meeting at the Hollywood Bowl last night, with ancient texts discovered in the Near East more than half century ago. There were questions, “How many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man?” There were parables, “God said to Abraham, ‘Kill me a son;’ “Abe said, ‘Man, you must be putting me on…’” There were warnings by the side of the road: “Businessmen they drink my wine/Plowmen dig my earth/None of them along the line/Know what any of it is worth.” And there were signs indicating No Direction Home. And by the way, this Hollywood Bowl was not the one north of Franklin and Highland—it had its own address: Desolation Row.

No, it wasn’t your typical Billy Graham Crusade message, but there was a cross on the hillside, and once you have heard this preacher’s voice, you will never forget it. I was sitting in the bleachers, where the grass is plentiful (I even got a generous hit from the Canadian friends just behind me) and the limousines are few (took a bus, along with hundreds of others from the Westwood Federal Building). Brought my notebook with me, in my special thrift shop purchased Bob Dylan Shoulder Bag, along with an apple, a bag of almonds and a bottle of water—which sailed right through the very vigilant Bowl security guards at the gates. Did not stop for the $16 sushi plate on the trail up to the top of the cheap seats.

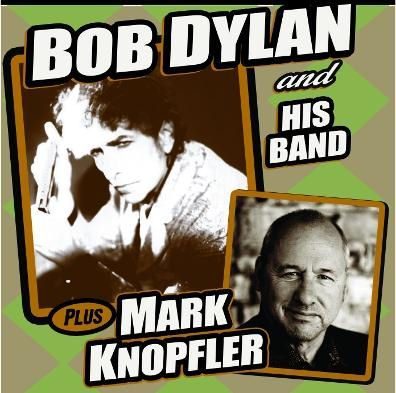

Everyone knew why we were there; we didn’t have to be told: Dylan has abandoned his once de rigueur unique introduction as “The Poet Laureate of Rock & Roll…” Nor was there a grand entrance a la Cleopatra carried on a coach; he just slipped furtively in from the shadows, took his seat behind the piano, and guitarist Charlie Sexton from his band started strumming a familiar tune, soon to be joined by steel guitarist Donnie Herron, guitarist Stu Kimball, bassist Tony Garnier and drummer George Ricelli; and then from on high, one of those Dead Sea Scroll sacred texts in the mouth of a gravelly tongued prophet began to intone in a voice so unmistakable you feel it in your bones before it even registers in your ears:

Cloud so swift,

Cloud so swift,

rain won’t lift

Gate won’t close

Railings froze

Get your mind off Wintertime

You ain’t goin’ nowhere.

The Prodigal Son was home and whatever else was going on in your life, you could sit back and revel in the soundtrack of America’s most alluring past, when “the original vagabond” wandered down from Hibbing, Minnesota’s frozen north country and grabbed a fast train to Greenwich Village in New York City, to launch the great 1960s Folk Revival. That was fifty years ago now, 1962, and we are still in his profound debt.

The opening song—You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere—was written in 1967 in the House at Big Pink in Woodstock, New York, where Dylan was holed up to recover from his motorcycle accident that broke his neck, and where he and his backup band (that eventually became The Band) recorded the songs that became known as The Basement Tapes, first bootlegged and finally released officially by Columbia Records. One of my seatmates on the bus ride home ventured that she lived in Woodstock at the time, and got to see Dylan jamming with other traveling musicians at the local Tinker Street Inn—such as Neil Young and Santana. She’s been a fan ever since. Those are the conversations one misses when taking a private car to the Bowl.

To Ramona from 1964s Another Side of Bob Dylan is one of his most personal, comforting love songs—a letter in verse to someone whose faith in life is tenuous, and whom Bob is determined to pull back from the edge, with this parting thought:

Everything passes, everything changes,

just do what you think you should do

And someday maybe, who knows baby

I’ll come and be crying to you.

Then he leapfrogged over several decades and settled on his Oscar-winning song from Wonder Boys—a daring departure from the author of The Times, They Are A-Changing that turns the anthem of hope on its head with: “I used to care, but things have changed.”

Back to 1974 and the divorce album classic Blood On the Tracks for Tangled Up in Blue, in which Dylan proclaims that in spite of their failure,

But me, I’m still on the road

Headin’ for another joint

We always did feel the same,

We just started from a different point of view,

Tangled up in blue.

How these bitter love songs can sound so tender now with the passage of time is just one of the mysteries that define Dylan’s quintessential genius.

It was about this time that one of those Canadian fans in the bench behind me leaned over and like Poe’s Raven tapped me on the shoulder with a question, “What are you doing?” He pointed to my Sharpie pen, busily jotting down Bob’s set list as I slowly recognized each song from his sometime bewildering rearrangements that departed far from their familiar recorded versions. I told him I would be reviewing the concert for FolkWorks, and wanted to get down each title. “You can understand the songs? He asked in amazement.” “Not really, I had to be honest; just a line here and there—but that’s enough to recover the title, and I know the words by heart so I hear it in my mind, if not my ears.” Now he was even more amazed. He didn’t have to know the words, he said quite deliberately; the music is so wonderful, “Dylan sounds cool even without knowing the lyrics.” “He plays his voice like an instrument,” and for emphasis, to make sure I appreciated what he was telling me: “Him [Dylan] and Elvis.” I shook his hand and thanked him for the observation.

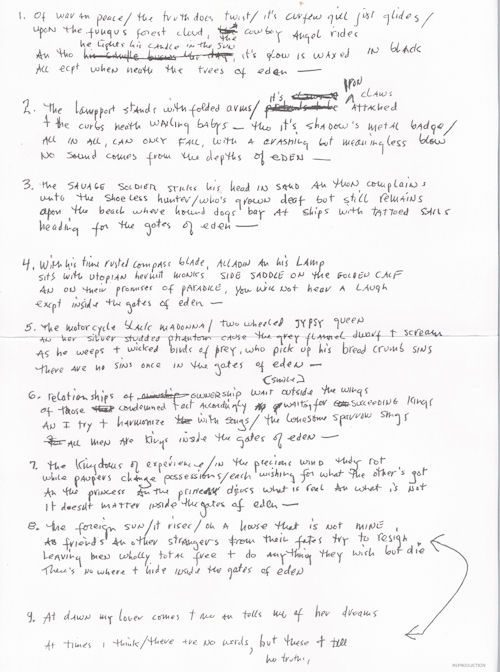

Then out of the corner of my ear I heard a phrase that stopped me up short: Desolation Row from Highway 61 Revisited—the song that starts out with an elliptical reference to the postcards of lynching that surfaced around the time Dylan was penning this definitive collection from the turning point in his change from folk to folk rock. Those cards were sold for a profit by and for the racists who did not mourn but rather reveled in America’s shameful legacy, and Dylan preserved their horror in this haunting masterpiece.

The young Canadian kept referring to Dylan as “Maestro,” and while I offered comments on the literary touchstones of this song, such as,

Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot are fighting in the captain’s tower

While Calypso singers laugh at them

And fishermen hold flowers,

he insisted on bringing me back to the musical authority of Dylan’s voice, which he compared without irony to “one of the Three Tenors.” Perhaps with a head cold.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ziHPNwJcpA

Our impromptu conversation kept pulling me away from what was happening on stage, but I couldn’t resist the utterly charming enthusiasm of this kid decades younger who reminded me of how I had first fallen in love with Bob Dylan as soon as I heard his voice—which at the time was described uncharitably as like “a cat being dragged across barbed wire.” It was so brazen you had to pay attention. Let other smooth-riding voices like Peter, Paul and Mary and Joan Baez make mainstream hits out of his early folk hymns; for me I always preferred the naked raw power in Dylan’s rough-hewn nasal blues vocals—the voice that prompted the dying Woody Guthrie to suggest that he “work on your singing.”

Perhaps I couldn’t tell the singer from the song, but it didn’t matter; I loved both. And the 71-year old Dylan kept going back to that great well of his mid-sixties treasures until he came to the vivid unforgettable opening strains of Ballad of a Thin Man—as dramatic and recognizable as the opening notes of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. As soon as I heard them I left our hovering sentences in midair and told this passionate young Canadian, “Wait, you have to listen to this—it’s Ballad of a Thin Man—which I realized from the first five notes in Am—Da, dada duh da. The inquisitive Canadian from Saskatchewan then asked me what the song was about; “That’s hard to say,” I had to admit, “but the chorus perhaps gives a hint:

Something is happening here,

but you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mr. Jones?”

Looking back, (sorry Bob, I know you told us not to) it was Joan Baez—then a Time Magazine cover girl and symbol of the emerging folk scare—who called him “the original vagabond” (later on, in her song Diamonds and Rust) and first introduced a young Dylan to the Bowl as a guest on her national tour in 1963. Ash Grove founder Ed Pearl produced that show—when he realized he needed a much bigger venue then his legendary folk club if he wanted to bring them out here. When Dylan was about to go on he couldn’t find his harmonica holder and asked Ed if he could find one for him. His brother blues guitarist Bernie Pearl was backstage and let Dylan borrow his.

(Memo to Bob: Bernie is still waiting for you to return it to him!)

Dylan didn’t need a harmonica holder Friday night; he held it in his hands as he ended Ballad of a Thin Man with a magnificent harp solo that filled the entire Bowl to the rafters. I have never heard a harmonica sound so glorious, except perhaps in the hands of Larry Adler—who played a much larger, chromatic version of the instrument.

Bob then turned to the song that gave Jimi Hendrix a hit—All Along the Watchtower from John Wesley Harding—his first album after the motorcycle accident that almost ended his career and his life—and introduced him to Nashville. “Let us not talk falsely now,” the preacher began to sum up his musical sermon, “the hour is getting late.”

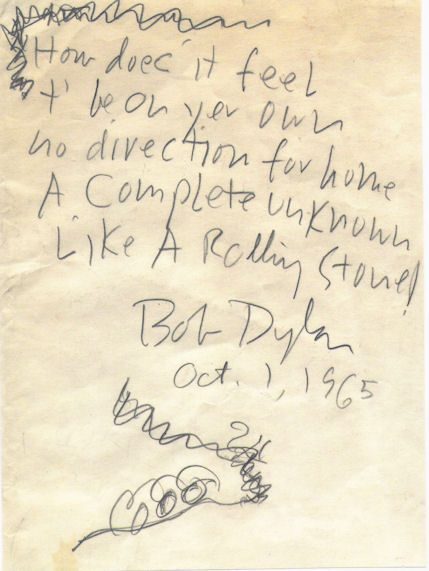

One could feel the sense of expectancy in the night air; were we going to hear the song Rolling Stone voted the greatest rock song of all time—the song that gave the magazine its name? Dylan didn’t disappoint; as much as he goes his own way, and continues to rearrange his old songs to suit himself and keep them surprising and fresh, he also recognizes his role as an entertainer and more than fulfilled the social contract with his audience.

Like an ancient text inscribed on papyrus dug out of the Qumran Cave in 1947, we heard this timeless troubadour tell his greatest story:

Like an ancient text inscribed on papyrus dug out of the Qumran Cave in 1947, we heard this timeless troubadour tell his greatest story:

Once upon a time

You dressed so fine

Threw the bums a dime

In your prime, didn’t you?

People call, say ‘Beware doll, you’re bound to fall

You thought they were all kiddin’ you…

How does it feel? How does it feel?

To be without a home

Like a complete unknown

Like a rolling stone.

This song has six verses!” [It feels like six, but only four] “That’s not standard in any songwriting,” I heard from the young Canadian whose running commentary acted like a Greek Chorus throughout the show. Women were standing at the front railing of the back bleachers, swaying in time to the music, and in a nod to a very different present than the song reflects, held up their cell phones to take pictures for their children, and grandchildren.

After the last notes faded, the lights dimmed on stage, and only after many rounds of applause and a Bowl-bellowing “Bob!” from my newfound Canadian friend Tyson Hoover, did they rise again, and Dylan came back out to sing the 1960’s greatest freedom and anti-war song, Blowing In the Wind—which I first heard him do on a PBS program with Odetta in 1962, soon after he wrote it fifty years ago this year.

With all his forays into various religious belief systems, Christian, Jewish and mystical, Dylan has always been more devoted to questions than answers—nowhere more eloquently stated than in this almost biblical anthem:

How many deaths will it take till he knows

That too many people have died?

The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind

The answer is blowing in the wind.

A true searcher, he inevitably frustrates those for whom the answers are more important than the questions—such as I met in the tunnel after the show, heading back to the Westwood bus on the other side of Highland Avenue. He had the traditional garb of an observant Jew, and handed me a newspaper devoted entirely to Dylan—with a lovely, thoughtful profile of the artist on the front, entitled, DYLAN—a Twelve Tribes Freepaper. The entire issue describes in minute detail how Dylan started as a protest singer, became a folk rock poet, converted to Christianity, then eventually found his way back to some form of the Judaism in which he was raised and Bar Mitzvahed, and finally seems to have wandered off into a less cohesive form of theology all his own.

Not good enough for this passionately evangelical Jewish sect who are committed to the return of the Messiah—whom they call Yahshua—and whom they trace back to one of the original twelve tribes of Israel, perhaps the Essenes who flourished from 200 BC to 68 AD, and whose library is thought to have been the source for the Dead Sea Scrolls. Down in the tunnel beneath the Bowl, I might as well have been in one of those 11 caves where archeologists found them sixty-five years ago. In the dim light, I might as well have been looking at some early true believer who left behind their texts, some of which were later found to contain a large portion of the Old Testament Hebrew Bible.

They want Dylan to come home to them—to declare his faith once and for all—like Joan Baez once wanted him to come back home to protest music and join the kids marching in the street.

They never understood that it ain’t no good—you shouldn’t let other people get your kicks for you. For in the end, as in the beginning, Dylan is an artist, not a preacher.

Welcome home, Bob. May you stay forever old.

Ross will be performing in the CTMS final concert from the CTMS Folk Music Center at 16953 Ventura Blvd, Encino, CA 91316 on Saturday evening, December 1, 2012. It is free and open to the public. CTMS would like you to RSVP if you are coming to the concert (with Fur Dixon, Tom Corbett and Susie Glaze) by calling 818-817-7756 or sending an email to info@ctmsfolkmusic.org Include in your message the number of people you will be bringing with you. See www.ctmsfolkmusic.org for further details.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com