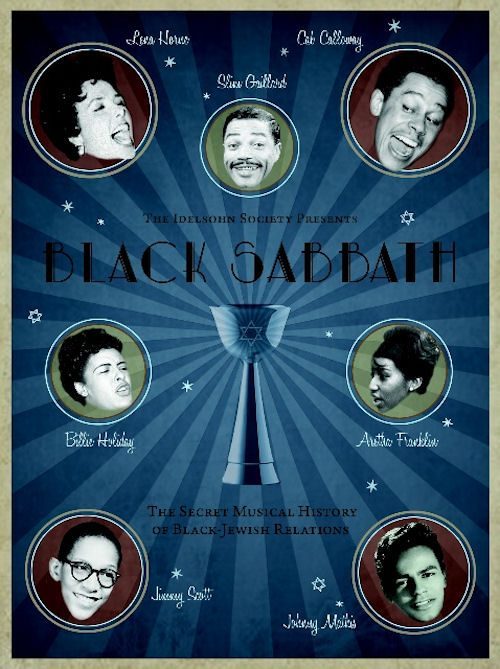

BLACK SABBATH – THE SECRET MUSICAL HISTORY OF BLACK-JEWISH RELATIONS

ARTIST: VARIOUS ARTISTS

TITLE: BLACK SABBATH: THE SECRET MUSICAL HISTORY OF BLACK-JEWISH RELATIONS

LABEL: THE IDELSOHN SOCIETY

RELEASE DATE: SEPTEMBER 14, 2010

You haven’t experienced the full aesthetic potential of If I Were a Rich Man from Fiddler on the Roof until you have heard The Temptations‘ rendition of the Broadway favorite. You can dig-a-dig-a-dum this and 14 other recordings of Black artists interpreting Jewish content in Black Sabbath: The Secret Musical History of Black-Jewish Relations, a CD released this September by the Idelsohn Society, an organization dedicated to collecting and preserving precious old recordings with Jewish content and exploring their significance.

You haven’t experienced the full aesthetic potential of If I Were a Rich Man from Fiddler on the Roof until you have heard The Temptations‘ rendition of the Broadway favorite. You can dig-a-dig-a-dum this and 14 other recordings of Black artists interpreting Jewish content in Black Sabbath: The Secret Musical History of Black-Jewish Relations, a CD released this September by the Idelsohn Society, an organization dedicated to collecting and preserving precious old recordings with Jewish content and exploring their significance.

This collection, packaged in a handsome mock-book with ample liner notes, can be appreciated on many levels. There are masterful interpretations by luminaries such as Billy Holiday, Alberta Hunter, and Cannonball Adderley. There are songs that stir memories of an era of American history or a state of American race relations that seems long past yet resonates emotionally. Some cuts may even provoke a negative reaction.

All of the above are part of the intention of co-producers Josh Kun and Roger Bennett, who compiled the recording while engaged in their larger, ongoing project known as Jews on Vinyl. They are co-authors of the 2008 book And You Shall Know Us By the Trail of Our Vinyl: The Jewish Past as Told by the Records We Have Loved and Lost. Anyone who was lucky enough to catch Josh Kun’s two lecture/listening sessions at the Skirball Cultural Center in July and August knows that the 39-year old scholar based at the Annenberg School of Communications has been searching for vinyl treasures in order to, as he stated in our interview, “use music as a helpful and acceptable guide to untangling the complexities of American identity.” His first lecture dealt with the African-American-Jewish connection while the second examined the interaction between Jews and Latinos through music. (Think albums titled Shalom, Mis Amigos and Bagels and Bongos.)

Kun’s July presentation material, some of which is reflected in the liner notes, acknowledged that the Black-Jewish cultural connection has been a bumpy ride. During the era of slavery, the Old Testament and particularly The Book of Exodus became a bond between the slaves of America and the former slaves of Egypt. This sympathy was reflected in the spirituals such as Let My People Go. But after emancipation and into the 20th century, Jews often became identified with the oppressive white population. As performers, some of them embraced minstrelsy, as shown on sheet music illustrations and performances in blackface by Al Jolson and others. Not endearing. With his hit Swanee, George Gershwin evoked a fantasy Dixieland that no African-American had ever enjoyed. In fact, he was pushing a myth that the descendants of slaves found repugnant although they sometimes pretended to embrace it in order to be accepted as entertainers. Meanwhile, Jews became record producers, theater producer, artist managers, lyricists, and composers. To some African-American artists, they appeared to be holding out precious opportunities for success; to others, they seemed to be taking advantage of artists not savvy in the white business world. Yet Jews helped form the NAACP and National Urban League in addition to being well represented in the Civil Rights Movement. The story continues and this well-wrought CD documents its twists and turns in a way that is both thought-provoking and musically satisfying.

In particular, the Yiddish content in Black Sabbath sparkles. Billie Holiday sings an abridged English version of My Yiddishe Mame, recorded in 1956 at a private home. Her rendition is heartfelt but never maudlin, sincere and musically fresh. In the voice of Lady Day, the words “my Yiddishe mame” and the self-sacrificing Jewish mother they represent take on universal meaning.

Alberta Hunter, at 84, interprets a popular Yiddish theater love song, Ich Hib Dich Tzufil Lieb in both Yiddish and English in an audio excerpt from a 1979 television program. According to the liner notes, the blues queen from the 1920s felt no warmth toward white Jewish blues singer Sophie Tucker. She told interviewer Dick Cavett that while Tucker “came nearer singing like a colored woman than the rest of them,” Tucker had no true claim on the blues because she had not “suffered like we’ve suffered.”

Cab Calloway is as playful as one would expect with his 1939 recording Utt Da Zay, one of several songs in his repertoire that blended Yiddish-isms with Black and Jewish rhythms. Josh Kun’s liner notes tell us, “Rack it up to Calloway’s close friendship with his Odessa-born Jewish manager Irving Mills who exposed Calloway to both Yiddish and the rhythms of Jewish prayer.” The result is sheer delight.

Playful may not be the right word to describe Slim Gaillard’s treatment of Yiddish culture – East European Jewish food, in particular – in Dunkin’ Bagel, recorded in 1945 with his Quartet. Over-the-top, clever, silly…You just have to let it happen to you.

Eartha Kitt may be the only singer who could take a three-word song and turn it into a giddy, multicultural romp. The fifties recording of Sholem Aleichem allows her to tout her linguistic prowess as she compares the Jewish “peace be with you” greeting to those used in other countries. The orchestral arrangement backs up her jubilant singing with spirit worthy of a klezmer band.

In a totally different mood, the velvety-voiced Johnny Mathis gives an earnest, musically mature rendition in ancient Aramaic of the cantor’s sung prayer for the Day of Atonement, the Kol Nidre. It is one of the Jewish songs that the young pop star included in a 1958 album of religious and spiritual songs titled Good Night, Dear Lord. In golden tones, he pours forth the melismatic wailing of a true cantor.

It would be hard to fault the charismatic Aretha Franklin for anything she has sung, but how she came to choose George Gershwin’s 1919 hit Swanee for a 1966 recording is a puzzle that the liner notes don’t really address. Yes, she belts out the number on her own terms, but the song conjures up a period in Black cultural history that evokes bitterness in many, as mentioned earlier.

Lena Horne’s recording of Now brought her voice to the civil rights struggle, responding especially to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King in 1963. At that time, she decided that she wanted to use her art to rally the Black population and wake up the whole country. Composer-lyricists Betty Comden, Adolph Green and Jule Styne obliged her with a searing commentary set to the melody of Hava Nagila. It was strong stuff. Radical lyrics like

I went and took a look in my old history book

It’s there in black and white for all to see…

and

Just don’t take it literal, Mister No one wants to grab your sister

kept the song off the radio and it never reached the mass audience she hoped for. But it is a testament to her life-long passion for social justice and the power of the word.

The Sabbath Prayer from Fiddler on a Roof gets wordless yet eloquent treatment from Cannonball Adderley in a 1964 recording devoted to tunes from that musical. Joined by saxophonist Charles Lloyd, pianist Joe Zawinul, bassist Sam Jones, drummer Louis Hayes, and Nat Adderley on cornet, Cannonball captures the meditative mood, at times restrained and periodically opening into an intense, encompassing sound.

Fiddler on a Roof inspired numerous artists to do their take on Sheldon Harnick and Jerry Bock’s memorable score. The medley that The Temptations recorded for their 1969 album On Broadway surely numbers among the best. It includes playful touches such as using the bass voice to step down the scale when describing the imagined fancy staircase in “If I Were a Rich Man” – “and one more leading nowhere just for show.” Their interpretation of Sunrise, Sunset is delicately haunting with its soft dissonances and use of chromaticism. This medley alone is worth the cost of Black Sabbath, but you get much, much more.

Audrey Coleman is a journalist, educator, and passionate explorer of traditional and world music.