BANJO DIARY: LESSONS FROM TRADITION

TITLE: BANJO DIARY: LESSONS FROM TRADITION

ARTIST: STEPHEN WADE

LABEL: SMITHSONIAN FOLKWAYS

RELEASE DATE: SEPTEMBER 11, 2012

Stephen Wade Paints His Masterpiece

In May, 1979 a 26 year old musician in his hometown of Chicago opened a newly-minted one-man show with the intriguing title: Banjo Dancing, or The 48th Annual Squitters Mountain Song, Dance, Folklore Convention and Banjo Contest…and How I Lost. It was a farrago of traditional banjo tunes and songs, clogging and storytelling from Appalachia to Brooklyn. I happened to be teaching high school there at the time, where I had moved to become the next Steve Goodman or John Prine, and went to see it. It was the greatest night I have ever spent inside of a theatre—and the star, creator and just barely containable ball of energy on stage was Stephen Wade.

In May, 1979 a 26 year old musician in his hometown of Chicago opened a newly-minted one-man show with the intriguing title: Banjo Dancing, or The 48th Annual Squitters Mountain Song, Dance, Folklore Convention and Banjo Contest…and How I Lost. It was a farrago of traditional banjo tunes and songs, clogging and storytelling from Appalachia to Brooklyn. I happened to be teaching high school there at the time, where I had moved to become the next Steve Goodman or John Prine, and went to see it. It was the greatest night I have ever spent inside of a theatre—and the star, creator and just barely containable ball of energy on stage was Stephen Wade.

Later that year he took the show to Washington, DC at the Arena Stage for a three-week run. Ten years later, when the show closed, Wade was standing on top of the record for the longest-running off-Broadway play in America. Over twenty years later and it is still one of the top five.

Like Jerry Seinfeld, Stephen Wade knew the show couldn’t go on forever and had an uncanny knack for knowing when to leave the stage—when it was still a mega-hit. Problem: he was still only 36 years old and had the rest of his life to live. Since leaving Squitter’s Mountain Wade has continued his deep exploration and excavation of American traditional music, in the process becoming the impresario of the banjo’s long and winding road into the hearts of several generations of young admirers of its original masters like Uncle Dave Macon, Hobart Smith, Pete Steele, Doc Boggs, Doc Hopkins, Virgil Anderson and Wade Ward. Stephen Wade has also produced several albums of his own to document not one but all of their respective styles, as well as the hard-driving three-finger bluegrass style that grew out of it and led to Earl Scruggs, who oddly enough was the first banjo player to inspire Wade to pick up the instrument. What was odd about it? That Wade did not devote himself to bluegrass, or like other virtuosos such as Bela Fleck, pursue experimental sounds that grew out of bluegrass and led to “world music.”

Check out this hour-long WETA-TV documentary on musician Stephen Wade. Catching the Music

Stephen Wade took the reverse path: starting with modern banjo techniques he assiduously buried himself in the vaults of the Library of Congress (the reason he chose to bring his show to Washington, DC in the first place) and started to retrace the route the banjo had taken from the African-American slave and minstrel show culture it spawned to the white mountain minstrels in the 1920s and 30s when the banjo first made its way into modern recordings.

Starting out in Chicago was particularly fortunate for the journey he embarked upon. At Chicago’s Old Town School of Folk Music Wade became, with Fleming Brown as his mentor, a student of the revival of early folk banjo. In particular Brown introduced Wade to the music of Hobart Smith, whom they regarded as the best traditional old-time banjo player of all. In 1963, when Wade would have been just 10 years old, Fleming Brown taped nine hours of Hobart Smith’s repertoire in a home recording studio that may be the most significant single recording session in the world of old-time music.

In Brown’s later years he bequeathed the entire collection to Wade, who, after Banjo Dancing closed, went back to where he had left off in 1979 as Fleming Brown’s most dedicated and determined student. He transformed the music on those tapes into his next show: In Sacred Trust: A Celebration of the Music of Hobart Smith. Wade also oversaw the tapes’ release as Hobart Smith: The 1963 Fleming Brown Tapes.

Shortly after, he also released two albums reflecting the wider range of his traditional repertoire that evoked his long-running hit show: Dancing Home (a solo banjo album which one reviewer described as the most beautiful solo banjo album ever made) and Dancing In the Parlor. Just as meaningful was his 1997 Rounder release—A Treasury of Library of Congress Field Recordings selected, edited and annotated by Stephen Wade. This essential record embraces the entire range of traditional music, as well as spoken word samples of preaching and brief commentaries from informants as well—it is the best single introduction to the riches of the Library of Congress Folk Music Archives. To highlight just one piece it includes Pete Steele’s legendary 1’27” performance of Coal Creek March. The virtuoso banjo instrumental, recorded by Alan and Elizabeth Lomax on March 29, 1938 in Hamilton, Ohio, is enhanced by Wade’s notes, which tell us that Steele practiced many hours to prepare for that one and a half minute claim on immortality. He also recounts the story behind it, from Lomax’s original field notes, as this remarkable tune grew out of a mine disaster in Coal Creek, Tennessee in which 600 miners were killed. A marching band came to play for the dead miners even as they were being taken out of the drift mouth of the mine, and that’s how the tune got started. When you listen to Steele’s propulsive driving ascending and descending banjo arpeggios—in a unique tuning made for this one particular piece—you suddenly have a whole unforgettable human portrait and dark drama in the foreground—the music takes on meaning that gives it a scope well beyond the pure instrumental. Perhaps that knowledge of folk music’s interconnectedness with American life and history is what keeps new generations wanting to retrieve it and make it available to the next. They aren’t just notes on a page, or even just notes on a recording—they are the lifeblood of human beings and together make up what Stephen Wade refers to as “an American musical mosaic.”

That brings us to his current project—a new Smithsonian Folkways’ album called Banjo Diary—Lessons From Tradition, which is being released in tandem with the publication of Stephen Wade’s amazing new 500-page compendium by University of Illinois Press—The Beautiful Music All Around Us: Field Recordings and the American Experience. The book (reviewed separately) opens up the world of these classic old-time musicians who influenced and inspired Wade to carry on their music and life stories.

This exquisite album demonstrates the lifelong durability of Wade’s musical sources, past banjo masters of frailing and of two- and three-finger styles which he has both thoroughly assimilated and recreated in ensemble arrangements that give them a lush grandeur that transcends their original string band and bluegrass underpinnings.

Here is the track listing: 1) Cotton Eyed Joe; 2) Train 45; 3) Arcade Blues; 4) Uncle Buddy; 5) Cuckoo’s Nest/Temperance Reel/Hop Light Ladies; 6) Home Sweet Home; 7) Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down; 8) Old Country Stomp; 9) Rocky Hill; 10) Little Betty Ann; 11) Cuckoo Bird; 12) Alabama Jubilee/Down Yonder; 13) Santa Anna’s Retreat; 14) Twin Sisters; 15) Wild Bill Jones; 16) Little Rabbit/Sheep Shell Corn; 17) Berkeley March/Under the Double Eagle; 18) Hand In Hand.

Sounds like a traditional old-timey record so far, does it not? So what’s new? As French philosopher Blaise Pascal once replied to the same question, “The arrangement is new.”

In various combinations for each track Wade is accompanied by a stellar cast including Mike Craver, Russ Hooper, Danny Knicely, James Leva and Zan McLeod on respectively pump organ, piano, mandolin, fiddle, guitar, Dobro, and bass. Quoting from the back cover, “This diary tells of an education written indelibly in a musician’s heart. 58 minutes, 44-page booklet with extensive notes and photos.”

Wade relies on Mike Craver’s almost circus-like pump organ texture to create his folk version of a wall of sound that holds together many of the tunes and songs he has chosen. He also lets other musicians shine as much as his own banjo sparkles—Danny Knicely on mandolin and bass, James Leva on fiddle, Russ Hooper on Dobro, and a great flat-picker Zan McLeod. The pump organ’s distinctive and evocative atmospherics pull you into a sense of not just listening from a single point of entry but rather of taking a journey into a land you may once have imagined but only now been able to realize. As familiar as Wade makes this musical territory sound, trust me—you haven’t been here before—at least not in any old-time or bluegrass group I have heard. It has flourishes of remembrances of things past—such as John Herald’s seminal guitar flat-picking in The Greenbrier Boys, or Mike Seeger’s neo-primitive fretless banjo solos in The New Lost City Ramblers, or even Roscoe Holcomb’s high lonesome tenor vocals. But Stephen Wade’s arrangements are so seamlessly integrated, and his fellow musicians so accomplished, that as Coleridge once defined great poetry, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. You soon realize that you are listening not just to great folk music, but to great music that has elements of folk in it, like Aaron Copeland’s Appalachian Spring. And though it never leaves folk music behind, it pulls it into new territory that has awaited this great explorer like the Pacific Northwest awaited Lewis and Clark.

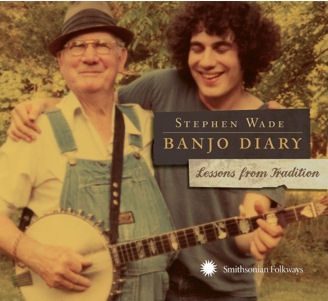

Both the connection to tradition and its compelling surpassing may be seen immediately on picking up this record—on the lovely cover photograph, where one of Stephen Wade’s early banjo heroes and mentors Virgil Anderson looks you proudly in the eye with his right hand curled over the banjo head, while standing just next to him with his left hand curled around the banjo neck to complete the illusion of one banjo player is a young Stephen Wade—with his eyes shyly closed and a mischievous smile, dreaming, as Yeats described his voyage in Sailing to Byzantium, of what is past, or passing, or to come.

Masquerading in these early days as a student who wanted merely to master and carry on the tradition, in this late masterpiece, Wade has finally stepped out of their long shadow and clearly become the original artist whose inclusive vision holds both in his hands. Yes he honors, ennobles and celebrates the past, but make no mistake, the man whose banjo this has become has followed his own drummer. Ever in search of sources, Stephen Wade has become a source.

Ross Altman’s upcoming performances:

Saturday, September 15 at 2:00pm – (With Professor Peter Dreier of Occidental College ) Tribute to Woody Guthrie during the centennial of Woody’s birth at the Allendale Branch of the Pasadena Public Library, 1130 South Marengo Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91106.; for more information call (626) 744-7260 or visit

Both events are free and open to the public.

Friday, September 28 at 7:00pm – (with San Diego folk musician Paul Svenson) Benefit for Americans United for Separation of Church and State. House concert in Garden Grove. For information visit www.AU.org

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com