Arlo Guthrie’s Southern Journey

Arlo Guthrie’s Southern Journey

The “Journey On” Tour Rolls into Royce; April 8, 2011

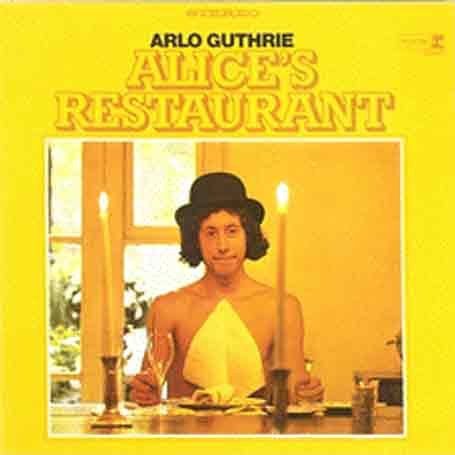

As every former hippie recalls with fondness, Arlo Guthrie, heir to the best pedigree in American folk music, used to tour in a “red VW microbus.” The very vehicle that took all the garbage out to the city dump on Thanksgiving, 1967 and thus cited for littering by Sheriff Obie. Yes we all know and love Arlo’s classic 18 minute and 34 seconds antiwar story song, Alice’s Restaurant.

As every former hippie recalls with fondness, Arlo Guthrie, heir to the best pedigree in American folk music, used to tour in a “red VW microbus.” The very vehicle that took all the garbage out to the city dump on Thanksgiving, 1967 and thus cited for littering by Sheriff Obie. Yes we all know and love Arlo’s classic 18 minute and 34 seconds antiwar story song, Alice’s Restaurant.

Fast-forward forty-four years: Arlo and his band, family and friends now tour in not one but two humongous earth-toned tour buses, with a hand-painted sixties surrealist logo for a previous “Lost World Tour” on the side. You could probably stuff a dozen VW microbuses in each one, and still have room left over for Alice’s Restaurant.

Give me the microbus, one six-string guitar, harmonica holder and mouth harp of Arlo’s first record, put it on one side of the scale, and then put the whole kit-and-kaboodle of his current small army of touring mates, vehicles, half dozen guitars and sound equipment on the other side, and watch it fly up and kick the beam.

But that’s just me. Two thousand aging former hippies filled Royce Hall last Friday night and had a wonderful time listening to everything Arlo sang and played with enthusiasm and gusto, and left him with a standing ovation at the end.

They also went away thinking that Leadbelly “wrote The Midnight Special and Goodnight Irene—and ‘most people have forgotten that,’” according to Arlo, which is tantamount to hearing it from the horse’s mouth.

But Leadbelly did not write The Midnight Special, which he learned in a Texas prison, the same prison where another African-American convict named James “Ironhead” Baker learned it, and John Lomax recorded it. Nor did Leadbelly write Goodnight Irene. He learned it from his uncle Tyrell, around 1912, and it was an old song even then. He did embellish it considerably with a surrounding cante-fable, which you can hear on his original Library of Congress recording in 1935, but that is not the version most people know or sing today, which is much closer to the original song Leadbelly learned from his uncle—since that is the version the Weavers recorded.

In short, Leadbelly sang them because they were great folk songs, and Leadbelly was a folk singer. So is Arlo Guthrie, if you ask me, and he should be respectful of traditional songs, and not try to gussie them up by claiming they were written by their best-known performers. The Kingston Trio did that all the time, claiming they “wrote” The Worried Man Blues and a dozen other traditional songs in which they changed a few lyrics to collect songwriting royalties from publishing companies.

Leadbelly never did that, and it is a disservice to his royal reputation to imply that he did.

But that aside, it is a real pleasure to hear Arlo sing and talk about The King of the 12-String Guitar. How many of us are able to say, as Arlo did, that his very first childhood memory was of standing—at the age of two years old—next to this “giant of a man,” and having him sing to you. Arlo couldn’t even verbalize it at the time, but he never forgot this big black singer who embraced him as a child in swaddling clothes, and sang for him.

Arlo then recounted how as an adult he decided to find Leadbelly’s grave, a southern journey that led to Shreveport, Louisiana, the site of one of Leadbelly’s best-known songs, Mr. Tom Hughes’ Town. It was there in a local bordello in the red-light district that Leadbelly evolved his distinctive and original ascending walking bass style of playing the 12-string guitar—which he patterned on the boogie woogie slide piano he heard in the houses of ill repute. That is also why he tuned his fabled Stella twelve-string down two steps so that D is actually in the key of Bb, because that was the key favored by both piano players and clarinet players who often accompanied them.

When they finally found it, in Mooringsport, Louisiana, where Leadbelly was born, a member of Arlo’s band commented, “He’s still behind bars!” So they jumped over the fence and spent the time singing Leadbelly’s songs on his grave, hoping he might hear.

When they finally found it, in Mooringsport, Louisiana, where Leadbelly was born, a member of Arlo’s band commented, “He’s still behind bars!” So they jumped over the fence and spent the time singing Leadbelly’s songs on his grave, hoping he might hear.

Then Arlo launched into one of the songs Leadbelly did write—Alabama Bound—on an electric 12-string, with his familiar walking bass:

I’m Alabama bound

I’m Alabama bound

And if the train don’t stop and turn around

I’m Alabama bound.

It was a joy to hear.

But a more famous train could already be heard off in the distance, and soon Arlo continued on his southern journey on Steve Goodman’s (unacknowledged) City of New Orleans, this time on the keyboard. Arlo’s head may be in Western Massachusetts, but his heart is clearly in southern Louisiana, with the ghost of Leadbelly and the musicians he helped out with his now legendary fundraising whistle-stop tour to replace the instruments they lost during Hurrican Katrina in August of 2006—including twenty-five baby grand pianos one donor brought down to the train station in Illinois for their trip.

In the first set Arlo had started on his journey south with another Leadbelly song—Pigmeat—which he played on keyboards. If you closed your eyes you could hear Leadbelly’s walking bass in the background, and if you opened them you could see the way he may well have first heard the song on Fannin’ Street in Shreveport, played on the barrelhouse piano:

Oh mama, you don’t treat pigmeat the way you should

If you don’t believe this is pigmeat

Ask anybody in your neighborhood.

Arlo then picked up his Martin M-38 six-string and played a perfectly realized blues accompaniment to yet another song he identified with New Orleans, St. James Infirmary (also known as The Gambler’s Blues) a song that has progeny and forebears all over the world, once documented in folklorist Kenneth Goldstein’s Folkways Album (from 1960) called The Unfortunate Rake: A Song Cycle that traced it back to Ireland in the 18th Century and eventually crossing the Atlantic to become the cowboy ballad Streets of Laredo, and southern blues, St. James Infirmary—which derived from an actual St. James Hospital in London. Arlo didn’t go into the history, which one can trace on the Internet at leisure; to get a beautifully recounted abridged treatment of the song’s evolution, track down my friend the late Sam Hinton’s Decca album, A Family Tree of Folk Songs, or its Folkways cousin, The Wandering Folk Song (still available on Smithsonian Folkways).

While to this listener the songs of Leadbelly were the heart and soul of Arlo’s show, he by no means ignored his father’s songs, or his own best known hits—except for the 18 and ½ minute classic that the audience tried in vain to get him to sing as an encore. “That’s why we make records,” replied Arlo, implying that you can buy the record, which was out in the lobby, (or hear it on YouTube for free). But I suspect that many of those shouting for Alice’s Restaurant already had the record; they wanted to hear him tell it again, just like Lennie asked George in Of Mice and Men, but to no avail.

Nonetheless, Arlo also told some wonderful stories, as he always does (see my accompanying essay, Mark Twain With a Guitar, for a fuller sense of appreciation of his storytelling); the best was of his wife (who was in the audience) being arrested as she was about to board a flight just an hour and a half from home in Washington, Mass. She called him on her cell phone and said, “You better come back and get me; I’m in handcuffs.” When Arlo turned the car around and got back to the airport he found that he had forgotten to remove a small tin from his suitcase that a fan had given him at a European show; on the top was a picture of a certain leafy plant known to have profound medicinal effects, and one word engraved on the bottom: Amsterdam. It was the perfect setup to Coming Into Los Angeles, another stop along the way.

But times have changed: even the cops were apologizing for having arrested her, and they all wanted his autograph and pictures taken with him.

They say that home is where the heart is; but not for this masterful folk musician—his heart is on the road, but not Woody’s road; Arlo’s road led south, down to New Orleans, Louisiana, with several stops along the way to visit the long lost grave of America’s greatest folk singer, who the two-year old Arlo was fortunate to hear just a year before he died on December 6, 1949. Imagine growing up in Woody Guthrie’s home, and having Leadbelly sing you lullabies. How can you keep from singing?

Here is Arlo’s set list, more or less, courtesy of Jessica Wolf from UCLA’s publicity department, with thanks.

|

Days are short |

Intermission |

Encore |

|

Pig Meat |

Mother’s Voice |

Under cover of night |

|

Darkest Hour |

Wake up dead |

My peace |

|

Evangelina |

Alabama Bound |

|

|

My Old Friend |

Highway in the wind |

|

|

LA |

Slow boat |

|

|

Deportees |

City of New Orleans |

|

|

Ladies Aux. |

Hymn |

|

|

When a Soldier |

Journey on |

|

|

St. James |

This land |

|

|

Prologue |

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com He will be performing an Earth Arbor Day show at Santa Clarita’s Central Park at 3:00 PM, Saturday April 16. On Saturday, April 30 he will be at the Roots Fest on Adams in San Diego (free). On May 1, May Day, Ross will be honored by Sunset Hall at their annual Garden Party. Call (323) 660-5277 or email wendy@sunsethall.org for tickets and information. And finally, on Tuesday evening, May 24, at The Talking Stick at 1411 Lincoln Blvd in Venice Ross will be hosting a 70th birthday party (in absentia) for Bob Dylan called: Forever Young: Bob Dylan’s Folk Years—1961-1964; $10.