Arlo Concert Review 2013

ARLO GUTHRIE

Don’t Believe a Word He Says:

The Lone Ranger in Concert at Irvine Barclay Theatre

On Campus at UC Irvine

Sunday, April 14, 2014

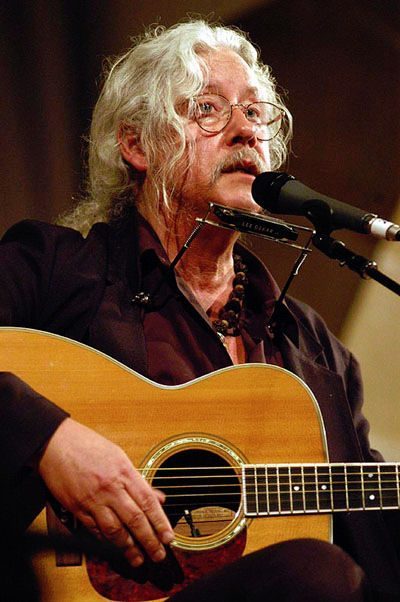

A long lone white-haired folk singer ambled onto the stage of the Irvine Barclay Theatre at UC Irvine yesterday with the most farfetched story you ever heard. Like some women claim to have run with wolves, he claimed to have been raised by Woody Guthrie, been dandled on the knee of Leadbelly, stowed away with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and learned the blues from Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee. Don’t believe a word of it; what will he come up with next? That Woody personally taught him the extra verses of This Land Is Your Land? He didn’t even have a band with him; that proves he must be an imposter; nor his multi-generational family—all of whom just happen to be named Guthrie too.

A long lone white-haired folk singer ambled onto the stage of the Irvine Barclay Theatre at UC Irvine yesterday with the most farfetched story you ever heard. Like some women claim to have run with wolves, he claimed to have been raised by Woody Guthrie, been dandled on the knee of Leadbelly, stowed away with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and learned the blues from Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee. Don’t believe a word of it; what will he come up with next? That Woody personally taught him the extra verses of This Land Is Your Land? He didn’t even have a band with him; that proves he must be an imposter; nor his multi-generational family—all of whom just happen to be named Guthrie too.

Sure, tell me another.

This long-haired hippie showed up with nothing but a Gibson J-200, a Martin M-38, a strange-looking 12-string that looked like it had been stolen from a Twilight Zone set; and an even stranger-sounding 6-string tuned to open G that he played an instrumental slack-key blues on he claimed to have composed himself.

Who is he kidding? Hey Arlo, somebody is touring this country all by himself, without Shenandoah, or any of your kids and grandkids, claiming to be you. Don’t you have a lawyer? Can’t you put a stop to this? This guy, whoever he is, put on a better show all by himself than I have heard your band do in twenty years. He showed what a folk singer is supposed to be; just a man walking along, as Woody once described himself; no fiddles, banjos, bass players, drummers and keyboardist (except of course for your grand piano). You really need to act now, Arlo, because this guy is good—so good he may steal your audience. People may get used to hearing folk music stripped down to its essence, the way you started out, a storyteller with a guitar.

Just in case you’re listening, I’ll let you in on a secret; I’ll even tell you his set list, because you should really learn some of these songs—they are some of the greatest songs in the American Songbag—you know, the one collected by Carl Sandberg, who you probably claim to have met too. St. James Infirmary Blues never sounded better—no, not even when Josh White played it. I kept waiting for the clarinet solo, but this amazing folk singer played all the notes himself—just finger-style on a vintage acoustic M-38—and up the fret board where Woody never ventured. It was a remarkable performance—those gambler’s blues from Old Joe’s barroom still haunt the American soul.

And his tribute to Leadbelly—well Arlo, you had to hear his twelve-string bass runs do a perfect simulation of Huddie’s Alabama Bound. Maybe he wasn’t kidding; somehow he absorbed the spirit of Leadbelly in every note and yet he was only four years old when he claimed to have met him. But the real kicker, Arlo, was when this curmudgeonly-looking (very close to the cowardly lion in The Wizard of Oz) raconteur told a real whopper about going to visit Leadbelly’s grave—that’s right, down near Shreveport, Louisiana (the place old Lead immortalized in Mr. Tom Hughes’ Town), and finding that it was cordoned off with a chain-link fence that prompted one of his bandmates to say, “Leadbelly’s still in prison.” So you and your midnight ramblers broke through the gate and sat right down on Leadbelly’s grave to serenade his attentive ghost with the Midnight Special and Goodnight Irene. Who would believe it? Not this old skeptic.

Really, Arlo, you’re known for some tall tales, but this guy on stage at UC Irvine’s Barclay Theatre managed to stretch the truth even further. Next you’ll be telling me that John Steinbeck—you know, the one who wrote The Grapes of Wrath and won the Nobel Prize for Literature–wrote your father a personal letter that said, if you’ll pardon my French, “You dirty little bastard—you wrote down in 12 [well, actually 17, but who’s counting?] verses what it took me a whole novel to write.” That was after Woody stayed up all night writing The Ballad of Tom Joad. This imposter on stage almost had me believing it, Arlo, until he left the truth behind altogether and bragged that one of your daughters had actually married one of Steinbeck’s sons—just to make peace in the family. You really ought to be more careful, Arlo, you know what your spiritual godfather Mark Twain (the one I compared you to in a previous column) once wrote: A lie can get halfway around the world in the time it takes truth to put its pants on.

But the heart and soul of this guy’s performance, Arlo, was your dad’s own songs; he shamelessly stole a whole bunch of them and sang them as well as the old man—you know the ones I’m talking about—Oklahoma Hills [which Woody co-wrote with his uncle Jack Guthrie] and which accidentally wound up on the hit parade in 1945—after Woody had studiously avoided any sign of commercial success; Deportee [for which Martin Hoffman wrote the music] and which this singer now claims inspired some reporters to actually track down the real names of the twenty-six Mexican farmworkers who perished in that Plain Wreck at Las Gatos [Woody’s actual title for the song]; and most amazingly, Arlo, he added that this coming Labor Day they are going to unveil a memorial to those “deportees” in Las Gatos, California. Who would have thought a folk song (for that’s what Woody’s songs have inescapably become) could do so much?

Then Arlo, this guy went out of his way to prove that your dad’s legacy is truly a living legacy, or as he put it so tellingly, “Woody Guthrie dead is still writing more songs than I am—alive!” That’s because your sister Nora has been busy plowing through the fertile fields of his unpublished manuscripts in the Woody Guthrie Archives in NYC—and finding living musicians to set hundreds of his lyrics to music—the ones he left behind without a clue as to how they should be sung—over 3,500 texts in all. It looks like Woody may become not only the greatest folk singer of the 20th Century, but the 21st Century as well.

He sang one of those recreated gems set to music by Janis Ian (who performed it herself in her recent CalTech concert I reviewed in FolkWorks): If I Could Only Hear My Mother Sing Again. Watch out, Arlo, this beautiful song stopped the show; it was almost as if he was singing it for your mother, not your grandmother. It showed that Woody had a sentimental side that doesn’t come through in many of his famous published songs, for this song was as sweet as an old hymn.

But it was Woody’s hard-hitting songs for hardhit people I came to hear; and this folk singer (who really did a bangup job looking and sounding like you, Arlo) did not disappoint. He called the show “Here Comes the Kid—the Tradition Lives” and presented it as a continuing part of last year’s Woody Guthrie Centennial. He told one of Woody’s great stories—found on one of those dusty mansuscript pages that sounded like it could have been written yesterday. “If a farmer robs a banker,” wrote your father, they’ll turn up the countryside looking for him—the sheriff, the deputies, the highway patrol, the town marshall, the cops, the troops, you name it; they’ll spare no expense tracking this farmer down.” Then Woody paused, “but if a banker robs a farmer…well, that’s a different story.” And then he (I almost said you, Arlo, the resemblance was so uncanny) sang Pretty Boy Floyd, Woody’s great ballad of the Oklahoma outlaw who became a folk hero (largely thanks to his song)—the one that includes one of Woody’s immortal lines: “Some will rob you with a six-gun, and some with a fountain pen”—and ends with this still timely observation—

As through this life you ramble

As through this life you roam

You won’t never see an outlaw

Drive a family from their home.

Woody wrote this song, what—75 years ago—and it still sounds as fresh as Robert Scheer’s commentary on KCRW’s “Left, Right and Center.” How did Ezra Pound define poetry? “News that stays news.” I guess nobody lived up to that definition better than Woody Guthrie.

Then, Arlo, this still hip hippie sang one of your father’s greatest critiques of modern capitalism in the form of a simple story recounting a true event—the 1913 Massacre in Calumet, Michigan—in which 73 children of copper miners were trampled to death in a hoax when the mine owners broke up a Christmas party by falsely yelling “Fire!” in a crowded theatre, and then blocking the escape doors so they could not get out. Just one of many crimes of early industrial capitalism, the kind that inspired Joe Hill and the Industrial Workers of the World, to organize and strike. But this crime has never been forgotten because of Woody’s song, which ends with the plaintive lament, “See what your greed for money has done.” That was all that Woody had to say, and it was enough.

What made this performance stand out though, Arlo, was the gentle, flowing arpeggio guitar accompaniment which acted as a counterpoint to the harsh reality of the story. Most protest singers would have pounded the strings to underscore the anger of the singer; but Woody’s story was so well told it needed no further emphasis; indeed the understated performance made it all the more powerful. Something to learn there, Arlo; he must have studied some of your old records, or perhaps Ramblin’ Jack Elliott’s version, who has made this song a standout part of his live shows for over forty years. I guess that’s what he meant by “The Tradition Lives,” Arlo, for this story is now a century old itself. And I was particularly moved by the additional knowledge—as indeed the performer seemed moved—that whenever you (or he) performs in Calumet, Michigan it actually stipulates in the contract that you have to sing this song. They know their own history and are determined not to forget it. How unlike Southern California they are, Arlo, where local history is always being paved over with the newest blockbuster billboard and postmodern architecture. Thank God for towns like Calumet, where one song can define a people’s struggle for the dignity of labor over a hundred years.

Thank God for Woody Guthrie. And thank you, Arlo, who carries on this tradition with such pride and grace—and great musicianship and storytelling. To hear you all alone up on that stage was a revelation—like hearing you in an old Greenwich Village coffeehouse in 1967, when only twelve people showed up, and your mom—Marjorie Mazia Guthrie said, “Don’t worry, Arlo, they’ll come back, and next time they’ll bring their friends.”

You couldn’t have done a better show; and the long standing ovation from a packed sold-out house proved your mother was right.

This land is your land. Just one more question, Arlo: who was that masked man?

On Saturday, April 27 Ross will perform in San Diego at Adams Ave Unplugged; for info see www.adamsaveunplugged.org; Sunday, April 28, Ross will perform in a benefit for the Jennifer Diamond Cancer Foundation American Folk Music Fest at the Leonis Adobe, 23537 Calabasas Rd, Calabasas, CA 91302. (818) 700-6900; on Sunday, May 19 Ross performs at the Topanga Banjo-Fiddle Contest and Folk Festival; for info on tickets, contest registration and volunteer opportunities see www.topangabanjofiddle.org; and on Saturday, June 15 Ross returns to Claremont for the 30th Claremont Folk Festival; for info on tickets, a complete list of performers and volunteer opportunities go to www.claremontfolkfestival.org

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com