ARITMIA – A MARRIAGE MADE IN MUSIC

Aritmia – A Marriage Made in Music

On first glance, the accordion and the acoustic guitar have little in common. The first is a large, hulking affair strapped on to the musician who negotiates its keyboard or buttons to achieve various pitches and manipulates bellows to control tone, timbre, and dynamics. The guitar, on the other hand, seems to melt into the musician’s body as tones are teased out by plucking and strumming and fingers achieve dynamics and texture with direct pressure. Furthermore, the accordion is a relatively young instrument, invented in Germany and Austria during the 1820s whereas the guitar’s roots stretch back to medieval Spain and even earlier if one considers its relationship to the lute and the Arabic oud. Since both instruments are capable of producing scales and chords as a kind of “one-man-band,” would they not seem redundant when paired?

On first glance, the accordion and the acoustic guitar have little in common. The first is a large, hulking affair strapped on to the musician who negotiates its keyboard or buttons to achieve various pitches and manipulates bellows to control tone, timbre, and dynamics. The guitar, on the other hand, seems to melt into the musician’s body as tones are teased out by plucking and strumming and fingers achieve dynamics and texture with direct pressure. Furthermore, the accordion is a relatively young instrument, invented in Germany and Austria during the 1820s whereas the guitar’s roots stretch back to medieval Spain and even earlier if one considers its relationship to the lute and the Arabic oud. Since both instruments are capable of producing scales and chords as a kind of “one-man-band,” would they not seem redundant when paired?

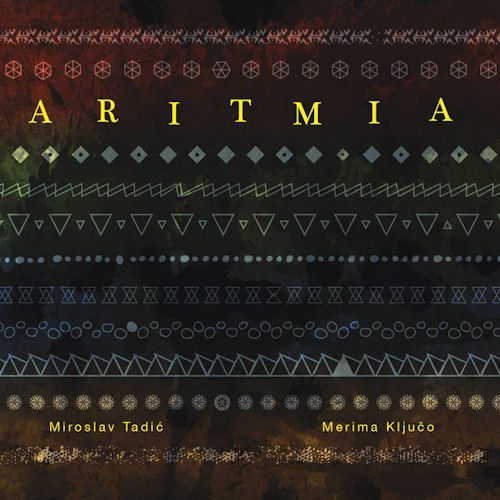

Nevertheless, two outstanding musicians, concert accordionist Merima Ključo and guitarist Miroslav Tadić, have created a stunning marriage of the two instruments in their newly-released CD, Aritmia.

I was lucky to hear the pair in performance at a concert on April 3rd sponsored by the Jewish Music Commission of Los Angeles. In a program mainly drawn from Aritmia, Ključo and Tadić complemented one another continually, trading melody and chord accompaniment back and forth between accordion and guitar so deftly that at times it seemed that we were hearing one instrument. Ključo’s instrument often sang brightly, sometimes bellowed, sometimes sighed and occasionally grunted—not your predictable accordion sounds. Tadić’s guitar wove elements of flamenco, Asian, and other strains into melodies and accompaniment. Their musical sensibilities were always in synch, paving the way for provocative but never showy improvisation.

Both Los Angeles-based musicians hail from the Balkans and take inspiration from the region’s folk music among other influences. Bosnian-born Merima Ključo also draws on Sephardic and Klezmer traditions and her solo repertoire includes classical, avant-garde and experimental music. She plays frequently as a soloist with European orchestras and has collaborated with Theodore Bikel among other luminaries. Miroslav Tadić, native of the former Yugoslavia, uses an approach to improvisation which combines and juxtaposes musical material as diverse as baroque, European classical and North Indian classical music, flamenco, Eastern European folk traditions, blues, jazz, and rock. Now a music professor at the California Institute of the Arts, he has a lengthy discography including recordings with the London Philharmonic, Los Angeles Opera, Terry Riley and orchestras world-wide. Beyond performing, Ključo and Tadić have composed innovative works for their instruments.

Both Los Angeles-based musicians hail from the Balkans and take inspiration from the region’s folk music among other influences. Bosnian-born Merima Ključo also draws on Sephardic and Klezmer traditions and her solo repertoire includes classical, avant-garde and experimental music. She plays frequently as a soloist with European orchestras and has collaborated with Theodore Bikel among other luminaries. Miroslav Tadić, native of the former Yugoslavia, uses an approach to improvisation which combines and juxtaposes musical material as diverse as baroque, European classical and North Indian classical music, flamenco, Eastern European folk traditions, blues, jazz, and rock. Now a music professor at the California Institute of the Arts, he has a lengthy discography including recordings with the London Philharmonic, Los Angeles Opera, Terry Riley and orchestras world-wide. Beyond performing, Ključo and Tadić have composed innovative works for their instruments.

The Balkan material on Aritmia frequently uses the Mixolydian mode with its bluesy tritone, often giving melodies a Middle-Eastern tinge. A number of the pieces toy with the pace, slowing down, speeding up, and sometimes ending with a rapid-fire finish and abrupt stop. Buciumeana, one of several dances on the album, comes from three towns in Romania. Beginning softly and mysteriously on the guitar with an underpinning of throaty sighs from the accordion, it has you on the edge of your seat wondering if the tune is going to erupt into loud, rhythmic dance music or fade into oblivion. The Braul or Sash Dance makes it easy to picture colorfully-clad Balkan folk dancers hopping to the melody that is first plucked, then played brightly on the accordion which sounds like a bass-pitched wind instrument. During that piece, Ključo achieves as pianissimo a tone as I have ever heard an accordion play. A rousing tune comes from the musicians’ published collection, Balkan Songs and Dances, in which the accordion produces different horn-like sounds.

Pieces from other Balkan forms display the region’s diverse musical heritage. Hajd’Sad Majka derives from Sevdalinka, a melancholy, reflective song genre from Bosnia, strongly influenced by Turkish music as well as medieval Spanish sounds brought to the region by Sephardic Jews. Gde Si Dušo, Gde Si Rano, a song composed by the prolific Davorin Jenko, considered the father of Serbian and Slovene 19th-century Romantic music, conveys bittersweet nostalgia. I sense an Argentine flavor in some motives, probably the result of Tadić’s Spanish-influenced improvisation.

Tadić and Ključo work three classical compositions into the album. The piece from Béla Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances obviously has the traditional roots that the Hungarian composer sought for inspiration but the interpretation here ends ambiguously “in mid-air.” Nana from Manuel de Falla’s Siete Canciones Populares Españoles, draws on a Spanish folk tune and becomes something very different in the hands of the two musicians. In one exquisite part of Nana, I imagine Tadić’s delicate plucking as tiny raindrops falling slowly on to the filigree web of harmonies produced by the accordion. The pair’s treatment of Erik Satie’s Gnossienne No. 1 seems humorously irreverent. While the original piano version is delicate, varied in dynamics and pace, and suffused with mystery, Ključo’s accordion carries the melody with a purposely ponderous quality reminiscent of a trombone or tuba. Satie would have enjoyed the contrast.

If you are intrigued about Aritmia, click on this link or this link for digital copies. It was released February 29, 2016.

Audrey Coleman is a journalist and ethnomusicologist who explores traditional and world musics in Southern California and beyond.