ALL ALONE WITH PAUL ROBESON

All Alone with Paul Robeson:

The Tallest Tree in the Forest

The Mark Taper Forum – April 19, 2014

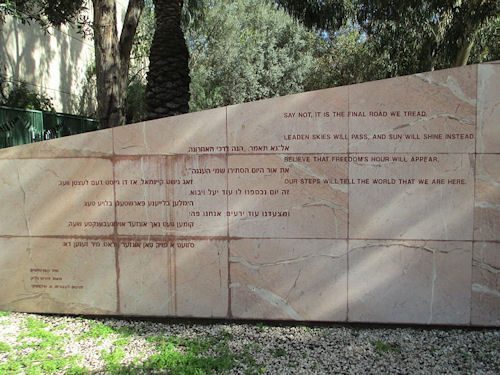

Who is the real Paul Robeson? The Tallest Tree in the Forest or the biggest windbag in Los Angeles? It wasn’t clear to this reviewer last night at the opening of the new one-man play about Robeson by actor Daniel Beaty at The Mark Taper Forum at The Music Center—until half way through the performance—when he sang Zog Nit Keynmol—Never Say—the Warsaw Ghetto anthem penned by Hirsh Glick, the 22-year old Vilna poet who wrote the song upon hearing news of the Jewish resistance to the Nazi attempt to liquidate the ghetto on April 19, 1943, as a birthday present for Adolph Hitler, who was born on April 20—today, as I write this review on Easter Sunday, Hitler’s birthday.

Who is the real Paul Robeson? The Tallest Tree in the Forest or the biggest windbag in Los Angeles? It wasn’t clear to this reviewer last night at the opening of the new one-man play about Robeson by actor Daniel Beaty at The Mark Taper Forum at The Music Center—until half way through the performance—when he sang Zog Nit Keynmol—Never Say—the Warsaw Ghetto anthem penned by Hirsh Glick, the 22-year old Vilna poet who wrote the song upon hearing news of the Jewish resistance to the Nazi attempt to liquidate the ghetto on April 19, 1943, as a birthday present for Adolph Hitler, who was born on April 20—today, as I write this review on Easter Sunday, Hitler’s birthday.

And there I was, on the 71st anniversary of the most heroic chapter in modern Jewish history, at the Mark Taper Forum at the Music Center (Broadway West), listening to Glick’s immortal song performed by Beaty’s Paul Robeson who sang it in the Soviet Union as his bravest act of protest on behalf of his friend poet Itsik Feiffer—whom he had just visited and had revealed to him in secret, the terror he lived under in Stalin’s USSR. That for me transformed a somewhat tendentious portrayal of the Voice of the Century into a magical night to remember. I started applauding as soon as the last note died away and was soon joined by the entire theatre audience—most of whom I doubt understood the full significance of what they had just witnessed.

That was the reason I wanted to attend the opening, because I knew it coincided with that anniversary, I knew what Robeson had done, and I wondered if director Moisés Kaufman would capitalize on it. He certainly did, and I am sure he did understand its significance. This powerful play—etched in blood and not in lead, as Glick’s last lines describe—put Robeson on stage in all of his moral complexity—both in terms of his personal failings toward his wife Essie (he seems to have cheated on her with most of his white co-stars, starting with British actress Peggy Ashcroft whom he met while engaged in the premiere of Show Boat at London’s West End) and his political failings—having remained an apologist for Stalin long after Khrushchev had exposed him for the mass murderer he was. Indeed Robeson accepted the so-called “Stalin Peace Prize” of 1952 with the same moral turpitude that Lindbergh accepted Hitler’s special Medal of Honor—The Order of the German Eagle. Unfortunately, the play left that little distinction out of the script.

It also left out two of Robeson’s more important songs: Joe Hill and The House I Live In—and yet made room for a number of forgettable additions to his oeuvre—such as Happy Days Are Here Again—if indeed he ever sang it, since it is nowhere on his collected discography.

It also left out two of Robeson’s more important songs: Joe Hill and The House I Live In—and yet made room for a number of forgettable additions to his oeuvre—such as Happy Days Are Here Again—if indeed he ever sang it, since it is nowhere on his collected discography.

However, since Beaty plays over 25 characters in this play about Robeson, it is entirely possible he was singing it in one of their voices rather than Robeson’s. Beaty’s seamless transitions from Robeson to his large supporting cast—including his long-suffering but never cowed wife Essie and former president Harry Truman demonstrate why this one-man play is so remarkable; it is a bravura, virtuoso acting performance from beginning to end—including his final failing days when he sank into depression and briefly hobbles about the stage like the Ol’ Man River he has at last become. Daniel Beaty thereby creates the full arc of Robeson’s epic life—from Phi Beta Kappa scholar at Rutgers—only the third African-American to attend—and two-time All-American football player whose gridiron exploits would later be excised out of the sports history books because of his charges from the US State Department and the House Committee on Un-American Activities that he was a “traitor” to his country.

The State Department revoked his passport in 1950 and the US Supreme Court did not re-instate it until 1958, making it impossible to do what he had done since 1927. In that year and throughout the 1930s and ‘40s his glorious singing voice was heard by a worldwide audience, including Spain during the Spanish Civil War, when he sang Los Quatros Generales (Four Insurgent Generals)—unfortunately left out of the show for Democratic Party theme song Happy Days Are Here Again. The play does a wonderful job though of vividly recreating Robeson’s performance for striking Welsh coal miners whose cause he championed (along with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt). The historical momentum of Robeson’s life—which intersected with many major events of the 20th Century—is captured with archival film footage cast on to the stage’s enormous back wall—images of World War II, the Soviet Union, the HUAC hearing (June 12, 1956), the FBI inquisitors who followed him around for most of his adult life, and most heroically and movingly the Peekskill, New York concert of 1949—the one that showed the screaming faces of racist upstate New Yorkers who let the concert be policed by the Ku Klux Klan infiltrated local police that pursued both Robeson and Pete Seeger back to their cars after the concert.

The indelible hate-filled images of ordinary American citizens looking eerily like earlier images of hate-filled Germans screaming at Jews brought home our domestic flirtation with fascism better than any text could do. Its chilling implications are all there to see in black-and-white (black-and-white newscast film footage, not print)—rescued from the vault of history by actor/playwright Daniel Beaty and director Moisés Kaufman and projection designer John Narun. Their visual proximity make you realize how close America came to completely losing what Lincoln so memorably called the “better angels of our nature” and succumbing to the worst evils of Nazi Germany. They also show how clearly America’s “race problem” (dubbed by black historian W.E.B. Dubois) was not just a problem way down south in Dixie, but penetrated all the way up to the bastion of northern liberalism—upstate New York, where Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass had both led the fight for the abolition of slavery in the 19th Century, and also tragically the home of the KKK.

Indeed, Paul Robeson’s life is probably the best known example of this, since he came from New Jersey, son of a former slave, and had to face racism at every turn, going all the way back to college and his first work experiences as a young law student. The “N” word is practically an un-credited co-star of this profoundly unsettling drama, making its first appearance as the first word Beaty-as-Robeson utters on stage—in the opening verse of the original version of Oscar Hammerstein and Jerome Kern’s Ol’ Man River—and reappearing at regular intervals—on the lips of both Robeson’s racist enemies and his celebrated literary/composer friends. It’s a daunting gauntlet he had to navigate throughout his life—until he finally and courageously rewrote critical lines of his signature song—replacing You gets a little drunk and you lands in jail with You makes a little fuss and you lands in jail and I’m tired of livin’ and scared of dyin’ with I must keep fightin’ until I’m dyin’ to turn a song of beleaguered resignation into the first civil rights anthem—when Paul Robeson was a one-man civil rights movement. This amazing one-man show paints its visual and musical portrait on a large canvas and if you are used—as I was—to taking your cultural helpings in small servings at local coffeehouses, public libraries, folk clubs, art museums and 99-seat equity-waiver theatres, you may be overwhelmed—as I confess I was until I got acclimated about halfway through—about the time Beaty-as-Robeson sang the Song of the Warsaw Ghetto. It was like gazing at the unadorned brightly-lit night sky in the Griffith Park Observatory instead of filtered through our smoggy haze, and seeing for the first time a whole galaxy of stars shining so brightly it takes your breath away.

Being at the Mark Taper Forum and the LA Music Center for the first time was a revelation—an astonishing insight into a whole new world—like seeing a major-league baseball game for the first time or reading Moby Dick after having consumed nothing but romance novels and spy thrillers. “Oh, this is what a real play is like,” I couldn’t help but feel; I had heard about them, and even read them in college, but I had never actually seen one until last night—and let me tell you—it was wonderful. The theatre has won me over—what a magnificent artistic achievement and inheritance from the ancient Greeks and Shakespeare—whose 450th birthday we celebrate this April 23rd.

Go and see The Tallest Tree In the Forest—it’s a bravura virtuoso performance by a great actor who has created a real play—with a beginning, middle and an end (Aristotle’s definition of a narrative) out of both the high and low-points of Paul Robeson’s life. With all of his failings, which Beaty does not flinch at or underplay—preferring to portray him as a real man and flawed hero rather than the left-wing statue he is so often reduced to—at the end Robeson is left standing—and humbly underscores his view of art and the extraordinary gifts he was given—that of a sacred trust. Daniel Beaty earned every minute of his spontaneous, grateful and prolonged standing ovation. He appreciatively shared it with his outstanding musicians on-stage, cellist Ginger Murphy, woodwind player Glen Berger and Music Director/Conductor and pianist Kenny J. Seymour. To see them all standing quietly and taking a bow—with noticeable tears in the eyes of star Daniel Beaty was one of the most moving moments I have ever felt in a theatre or live performance of any kind. It was fully human—as was Paul Robeson himself.

The Tallest Tree In the Forest continues until Sunday, May 25. Tickets range from $20 to $70. To get the bargain tickets of $20 go on-line to http://www.centertheatregroup.org and look for the icon for hot tix.

If you read the LA Times story Paul Robeson to the Power of 2 in Saturday’s Calendar section you will see that there is a second play about Robeson in town at the same time, called simply “Paul Robeson,” at the Nate Holden Performing Arts Center, a revival of the late Philip Hayes Dean’s original 1977 Broadway production starring James Earl Jones. This one stars Keith David, who at 57 is 20 years older than Beaty. I am seeing that performance this evening (both theatre directors were kind enough to give me press passes) and will review it separately. If there are comparisons to be made at that point I will, but I did not want to be forced into making comparisons, preferring to let each stand on its merits. As David says at the end of the interview, “There’s room for a lot of Robesons. Everyone brings something a little different, and they’re all welcome.” Amen.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com