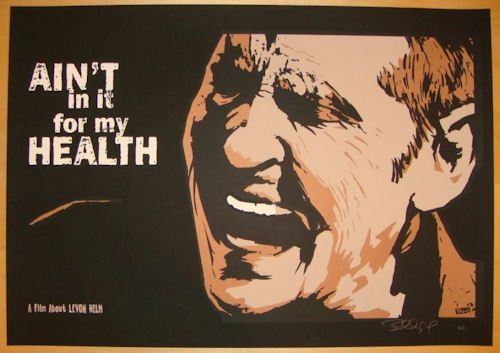

AIN’T IN IT FOR MY HEALTH: LEVON HELM

The Voice:

Ain’t In it For My Health:

A Film About Levon Helm

Directed by Jacob Hatley

SEE IT NOW: It’s playing at two local Laemmle Theatres this weekend, the Playhouse 7 in Pasadena, in Claremont, at 11:00am and at the Aero in a double bill with The Last Waltz on July 5th.

My voice is not one of the smooth-riding kind, wrote Woody Guthrie, ‘cause I don’t want it to sound smooth; none of the folks I know have got smooth voices, and yet they sing louder, longer and with more guts than any smooth voice I ever heard. I’d rather sound like the ash cans of the early morning, like the cowboys whooping, like the lone wolf barking.

My voice is not one of the smooth-riding kind, wrote Woody Guthrie, ‘cause I don’t want it to sound smooth; none of the folks I know have got smooth voices, and yet they sing louder, longer and with more guts than any smooth voice I ever heard. I’d rather sound like the ash cans of the early morning, like the cowboys whooping, like the lone wolf barking.

I think of Woody’s description of his own voice every time I hear Levon Helm, for it describes not only its timbre, but the world it expressed as none other in modern music. To me he was the Voice of America, as I wrote in my obituary last year, as surely as was Edward R. Murrow a generation before.

His legion of fans will be delighted to see Jacob Hatley’s new film documentary Ain’t In It For My Health: A Film About Levon Helm.

Since the film confronts them head on there is no reason to beat around the bush here: He had his drug problems long before the Betty Ford Clinic opened, when only Lenny Bruce could have helped him, and we all know how that ended; as Bob Dylan wrote in a beautiful elegy:

Lenny Bruce is dead

But his spirit’s living on and on;

Never did get any Golden Globe award

Never made it to Synanon…

Neither did Levon Helm, but throat cancer almost sobered him up in a hurry; and after his diagnosis he wasted no time in almost cleaning up his act. Albutnotquitemost, as e.e.cummings once put it, since it seems he never gave up smoking, or drinking for that matter, which leads inexorably to the late revelation of the source for this movie’s captivating title: Ain’t In it For My Health.

In 1975 Robbie Robertson, The Band’s principal songwriter, came to him and suggested it was time to quit, because it was “taking a toll on our health, and on the collective health of The Band.” Helm’s existential reply was, “I’m a musician; I’m not in it for my health.” Then he expounds, “If I wanted to live a healthy life I would have become a pastor.” He lived for one thing, and one thing only—to make music.

So what did he do after receiving his throat cancer diagnosis ten years before it finally defeated him? Did he quit smoking? Not on your life. He recommitted himself to his music, determined to get as much music on record as he could before he rejoined Richard Manuel—whose suicide is treated with both shock and awe in the film. “He was the strong one, we all thought,” says Levon; until he wasn’t.

This heartbreakingly beautiful movie is a testament to his courage under fire, his resilience and authenticity, and his Ozark Mountain upbringing: call him The Arkansas Traveler, born in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas in 1940. He knew he had to get out of Turkey Scratch if he wanted to bring to life the music he heard in his head and heart; he wound up in Woodstock in 1967, ground zero of American folk rock’s rebel genius Bob Dylan. Levon Helm and the Band moved into the basement, and created the most important recording studio in the country—the Sun Records of the late 1960s, the Brill building of roots country, with this gravel-tinged Arkansas dirt farmer as their drummer and lead singer. They substituted grit for slick, and Highway 61 for Tin Pan Alley.

Starting with Dylan’s bootlegged Basement Tapes they eventually found their own voice and post-Dylan song-craft, with Canadian Robbie Robertson using the Ozark tenor of Levon Helm for his muse—turning Helm’s spiritual and ancient American soul into modern anthems—from The Weight and Up On Cripple Creek to The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. They found a way of threading a very fine needle, embracing the South’s history and sensibilities without giving in to its contemporary Confederate sympathizers.

With four Canadians in the group they needed one essential American voice to make those songs ring true—and they found it in Helm. As I wrote in my obituary for him last year, as much as Edward R. Murrow, Levon Helm was the voice of America.

With four Canadians in the group they needed one essential American voice to make those songs ring true—and they found it in Helm. As I wrote in my obituary for him last year, as much as Edward R. Murrow, Levon Helm was the voice of America.

When he sings, “There goes Robert E. Lee,” you can picture him at Appomattox with Lee off in the distance; he could have walked off the screen of the movie Lincoln and you would have no trouble recognizing a rebel soldier in his slender, haunted, wizened face.

And when you hear the first song in this tribute documentary, Dylan’s When I Paint My Masterpiece, you feel why Helm made it his own. “The streets of Rome” are just as alive as they would have been to Caesar; and when he sings, “Ancient footprints everywhere,” you can hear the centuries in his voice.

Levon has a disarming smile that belies the on-going struggle against cancer that consumed so much of his time and energy during his final decade. And yet his defiant optimism shines through every battle he confronts with such dignity.

Laryngectomy (the surgical removal of his cancerous larynx) was the preferred and recommended treatment to save Helm’s life; but he refused it because it would have meant the end of his life as a singer. So Levon made a deal with the devil at his own personal crossroads—as profound as Delta blues guitarist Robert Johnson. In effect he said, “Give me ten more years and you can take me,” for that is what it turned out to be.

The movie does not flinch from the most delicate scenes where he is looking at the crystal clear images of his vocal cords, showing the cancerous growth that replaced his high lonesome tenor with a gravel pitted, though still hauntingly expressive, voice. He dealt with the rapacious effects of his illness one day at a time; some days he was fine, and the very next he developed laryngitis and couldn’t even talk let alone sing. And some of these most disheartening moments struck just as he was about to go on stage, and forced him to cancel performances at the last minute. The most moving of these documented ravages of his disease came after he had appeared at an outdoor venue in Ohio, and had to sing with the harsh wind blowing into his windpipe against his vocal cords. By sheer force of will he sang through the show, but by the next day he was mute, and the show did not—could not—go on.

And yet the Gods of folk music seemed never to completely abandon him, and to intercede when most needed: at the recording session for his singular contribution to The Lost Notebooks of Hank Williams, an album that grew out of the discovery of 24 pages of unfinished songs by the Shakespeare of Country Music. Though never adequately identified in the film itself, those manuscripts are shown being perused by Helm and his co-producer Larry Campbell, formerly a guitarist in Bob Dylan’s more recent touring band, and their struggling attempt to finish the song You’ll NeverAgain Be Mine. It is one of the few times the actual craft of songwriting has been successfully documented on film. Director Jacob Hatley takes his time in telling the story, allowing Campbell’s first valiant efforts to complete the last verse to take hold in the viewers imagination—so much so that I found myself trying to complete Hank Williams’ song and realizing how difficult it is to write so simply as Hank did. Inadvertently it thus became a profound lesson in how (not) to write a song. Levon realizes as he is listening to Larry throwing out lines that they are not going to work—and he doesn’t have to say a word to get his point across! His face and closed eyes are so expressive you realize he is assessing the lines and communicating in silence that he is going to have to do it himself—Larry won’t be able to do it for him. His raised eyelids tell us everything we need to know—this is a Hank Williams song by God, and it has to be done right. It can’t be hurried.

Only a half hour later does the film circle back to this unfinished song, and let Levon’s brilliantly simple lines enter into the soul of country music’s greatest songwriter. You see and hear him recording the song that earned its place on the final album, alongside Bob Dylan, Merle Haggard and Hank’s granddaughter, Holly Williams—with Bocephus himself, Hank Williams, Jr.

What makes Levon’s last verse so compelling is not only its simplicity, but its hardwon optimism—adding a layer of redemption to Hank’s despair: “My lonely heart holds no hatred or pain/Though sometimes I feel it may die/But it always beats stronger/When I hear your name/And it won’t let me say goodbye.”

But the narrative force of the film has a larger arc: Will Levon Helm win a Grammy for his comeback album Dirt Farmer, which we find has been nominated as the film opens. The title comes from a Tracy Schwarz song, Poor Old Dirt Farmer—of the late great New Lost City Ramblers. But it might as well have come from Helm’s own life—as we see documented in the movie—where he spends as much time on a tractor as he does in front of a microphone. It puts his story in a real-life perspective to see where his voice and passion come from—the earth itself. His beautiful expressive face and hands bridge two worlds—the highest spiritual aspirations with the land and “mud beneath my feet.” It is an ideal metaphor for an American national treasure, and captures his strength as well as his vulnerability.

The well-drawn suspense of will he or won’t he win is woven into the parallel story of Helm’s over all bitterness toward the music business in general and the Band’s personal history in particular. He dismisses the importance of the Grammy, even as he prepares to receive their Lifetime Achievement Award—to be presented at the same ceremony for which he has been nominated for a competitive award in the Traditional Folk category. In particular he is profoundly resentful that Robertson mined his life and background to create their songs, but was the only one to receive royalties on them—essentially the only one to be able—literally in the Marxist sense—to capitalize on them. That of course was not in the strictest sense Robertson’s fault—it is rather the way copyright laws are written and publishing royalties assigned by the recording industry.

Notwithstanding, Levon Helm’s sense of basic fairness was violated to the point that as he surveyed The Band’s legacy he said in the most pointed fashion that it was all over by 1970 and their second album—i.e., Music From Big Pink (1969) and The Band (1970). In the wake of this powerful undertow to the film I couldn’t help but be moved by hearing from other sources that Robbie Robertson visited Helm in the hospital during his final days; if a final reckoning and reconciliation was possible it was a longtime coming, but surely to be welcomed.

In the movie’s gratifying last scenes we learn that Levon Helm’s Dirt Farmer did indeed win the Grammy for best Traditional Folk Album of 2008. As thrilling as it seemed to be for this great artist to achieve real recognition from the industry he couldn’t help but feel exploited by, it was more of a tribute to the Recording Academy and Grammy voters that they had finally earned the respect of America’s most gifted roots musician. The hard times he had endured during his last years should not have happened in a country that pretends to value tradition and great music—and yet leaves its most authentic voices to fend for themselves.

Let me enumerate some of these injustices: Levon Helm lived in constant fear literally of not being able to afford the roof over his head and losing his home. At the age of 70 he had to hold rent parties (his fabled “Midnight Rambles”) to keep from being foreclosed on. It was only the kindness of strangers that kept him from being thrown out into the street. They gathered every month to support his small community of Woodstock musicians who put on a great show every time for them, and provided Levon enough to get by—much like the Almanac Singers in the 1940s held Hootenannies at their group home (“Almanac House”) to pay the rent. But this was in their heyday, when Pete and Woody and Bess Hawes were young and healthy and able to live on the hoof. A great musician should not have to live hand-to-mouth from month to month when they are 70 years old and dying of cancer. Not in a country for whom their music has been its life’s blood for forty years. Shame on us!

And praise be to filmaker Jacob Hartley for telling this epic tale of Levon Helm’s fight for survival and human dignity that animated his best work going back to The Band’s halcyon days as Bob Dylan’s comrades-in-arms, their folkrock and roll superstardom, and finally his stripped-down-to-essentials bare bones solo career as one of the last of the breed—a dyed-in-the-wool folk singer if there ever was—hacking, growling, whispering, sometimes barely audible, but through it all the voice that carried America on its back—this exile from Turkey Scratch, Arkansas.

America owed him something; and all they could give him was a Grammy. See this movie; and if the Motion Picture Acaemy is listening—look no further for the best documentary of 2013. That still-standing House at Big Pink should have an Oscar to put up over its fireplace. For if American folk music began with Woody Guthrie in Okemah, Oklahoma, it found its greatest voice right here; and it never had a better friend than Levon Helm.

On Saturday afternoon at 2:00 PM, August 31, 2013 Ross will present Musical Legacy of the Great March for the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington (August 28, 1963), including songs from the 1963 Newport Folk Festival, at the Allendale Branch of the Pasadena Public Library 1130 S. Marengo Ave.(626) 744-7260 (free).

On Sunday morning at 10:15am, September 1, Ross will present his 33rd annual labor program at The Church in Ocean Park, at 2nd and Hill in Ocean Park (310) 399-1631 (free and open to the public).

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com On Thursday evening, August 1, 7:00 to 10:00pm, Ross will host Concert for Bangladesh at The Talking Stick, 1411 Lincoln Blvd in Venice. Donation is $10 plus one drink or food item to support the venue.